7-Million-Year-Old Fossils Show How the Giraffe Got Its Long Neck

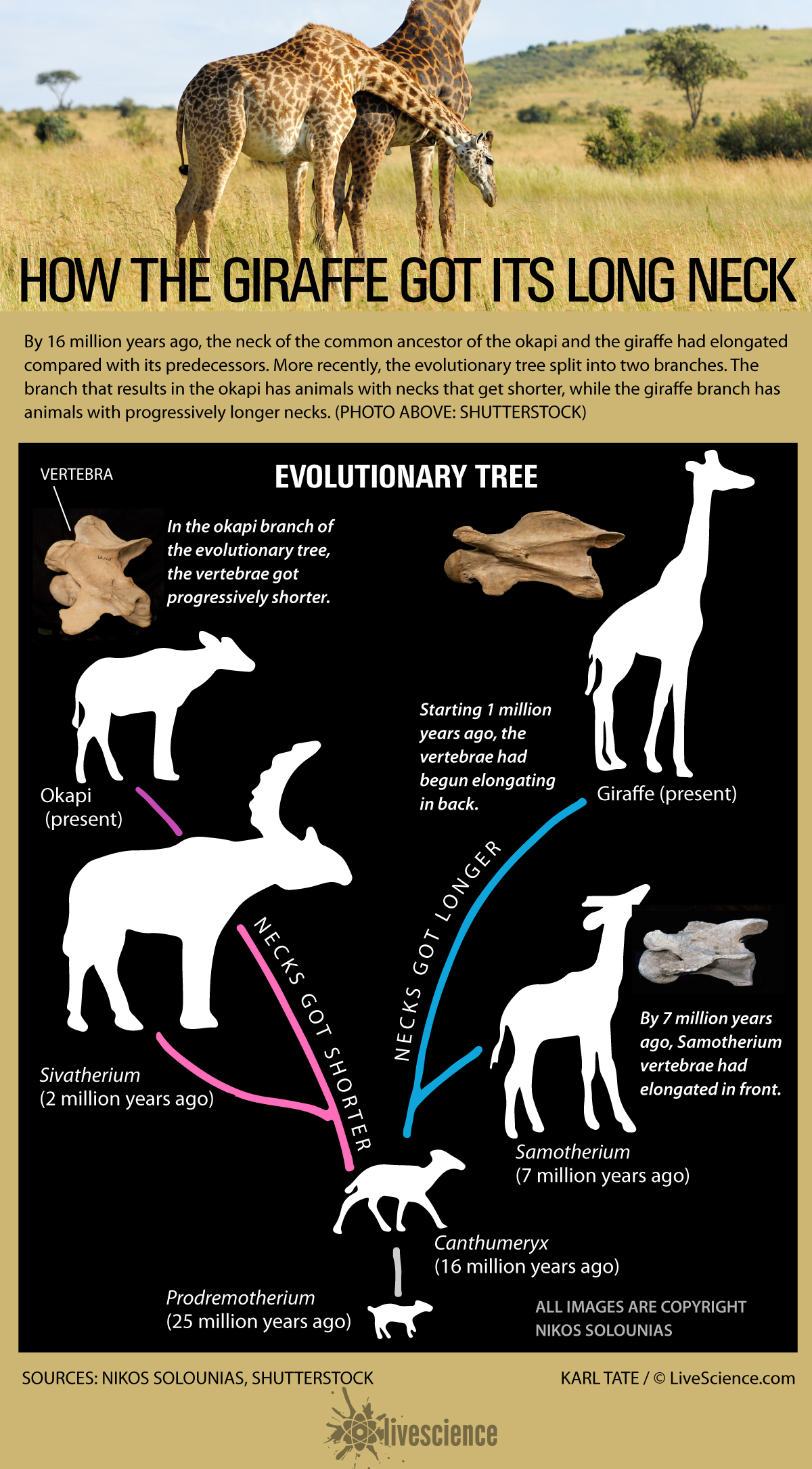

For years, there has been scant fossil evidence showing how the giraffe evolved to have such an admirably long neck. But now, the remains of a 7-million-year-old creature with a shorter neck provides proof that the giraffe's iconic feature evolved in stages, lengthening over time, a new study finds.

The researchers are calling the remains of this ancient beast true "transitional" fossils, not only closing an evolutionary gap in the rise of Earth's tallest animals, but also providing concrete evidence of how one creature evolved into another.

"We actually have an animal whose neck is intermediate [in length] — it's a real missing link," said Nikos Solounias, a professor of anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) College of Osteopathic Medicine and the lead researcher on the study.

The creature in question — Samotherium major —lived during the Late Miocene in the forested areas of Eurasia, ranging from Italy to China, Solounias said. [In Photos: See Cute Pics of Baby Giraffes]

Researchers first discovered S. major fossils in 1888, but the creature's importance wasn't realized until much later, said Solounias, who first got a glimpse of the fossils at a museum in Germany in the 1970s when he was working on his doctoral thesis.

"When I saw these bones, my breath was taken away," Solounias told Live Science.

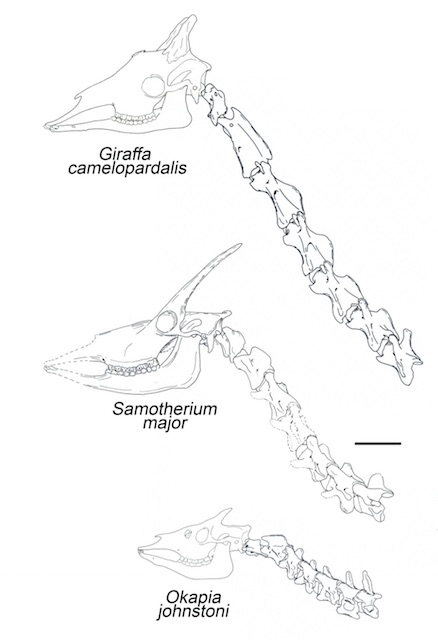

The neck bones of S. major were shorter than those of a modern giraffe, but longer than those of the short-necked okapi, the giraffe's only living relative. Solounias didn't have the time or money to study the bones at the time, but he and his colleagues returned to them this year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They analyzed the neck bones of four S. major individuals, three giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) and three okapis (O. johnstoni). On average, giraffes had 6.5-foot-long (2 meters) necks. In comparison, the necks of S. major were about 3.2 feet (1 m) long, and the okapi necks extended about 1.9 feet (60 centimeters).

The findings surprised them: Not only was the length of the S. major neck between that of the giraffe neck and the okapi neck, but its shape and the angles between bones were also intermediate.

If the researchers were to paint an S. major neck, color-coding its giraffelike parts red and its okapilike parts white, the top of the neck would be covered with red and white dots, and the bottom of the neck would be pink, the researchers said.

"In every way, it's intermediate," said study first author Melinda Danowitz, a medical student at the NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine. "It's completely between the two living species."

The researchers also examined how S. major held its neck. The findings are preliminary, but based on the position of the bones, it appears that S. major held its neck vertically, as a giraffe does, instead of horizontally, as a cow does, they said.

The researchers also noted that S. major is not a direct ancestor of the giraffe. "It's near the direct ancestor," Solounias said. "But the direct ancestor has not been found yet."

The finding is "very important," said Donald Prothero, a research associate in vertebrate paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, who was not involved with the new study.

"Contrary to what some creationists say, we do have transitional fossils that show how one kind of animal evolved from another," Prothero told Live Science. "We finally have fossils that show how giraffes got their long neck from short-necked ancestors, which most fossil giraffids were."

The findings will be published online today (Nov. 25) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.