Mysterious Egyptian Mummy Has Head Full of Dirt

A mysterious Egyptian mummy dating back about 3,200 years has dirt in the skull, a new investigation reveals.

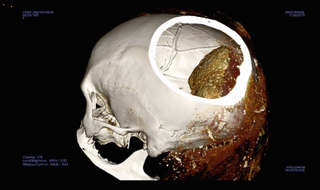

The presence of what looks like dark sediment inside the mummy's head is bizarre, said the researchers, who used computed tomography (CT) to peer inside the mummy. Not only was there some sort of sediment in the head, the researchers found, but the individual's brain remains inside, too.

"It's some form of material added into the brain case while the brain was left inside," Jonathan Elias, the director of the Akhmim Mummy Studies Consortium, said in a statement. "We have not seen that particular pattern before." [Video: See Scans of the Mummy Skull]

Elias made his comments in a video recorded as the mummy was being scanned at the Stanford University School of Medicine in California, where researchers have previously used CT to delve into the remains of both human and crocodile mummies.

The latest mummy to undergo this high-tech scrutiny is named Hatason, though researchers said they believe this is a nickname assigned after death, not the individual's real name. According to Stanford, the mummy was transported from Egypt to San Francisco in the late 1800s and was displayed at the California Midwinter International Exposition in 1894. In 1895, the mummy joined the collection of San Francisco's de Young Museum.

The mummified body currently resides at the Legion of Honor museum in San Francisco. Whoever sold the mummy in the 1800s probably named it Hatason to bring to mind the royal name of queen Hatshepsut, but this mummified individual was no royal. Her coffin depicts a woman in the standard dress of an everyday citizen, though it's not clear whether the coffin the mummy rests in now was originally the individual's; mummy buyers of the 1800s reused coffins haphazardly.

The scans are still being analyzed, but the initial look inside the mummy, on Nov. 24, revealed some odd details. The mummy had no amulets in its wrappings, only a metal tack probably used by a museum curator to keep the mummy's wrappings together. The bones are jumbled inside the wrappings, which are still shaped into a mold of the ancient woman's body. The pelvis, which is what researchers typically use to determine gender, had collapsed, but Elias said the mummy's skull looked female.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fact that the brain was not removed from the skull suggests the individual lived during the New Kingdom, between the 16th and 11th centuries B.C., Elias said. In mummies created after that period, he said, the brain was always removed.

Someone was probably experimenting with mummification techniques at the time, though. Adding sediment to a skull with the brain inside is a method not seen before, Elias said. It's the kind of detail only a high-tech CT analysis could uncover without destroying the mummy, he said.

"Mummies of this period are not very plentiful, so each time we have an incremental change in the technology, we learn much more and are able to say much more than in the past," he said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular