Ancient 'Wand' May Be Oldest Example of Lead Work in the Levant

A lead and wood artifact discovered in a roughly 6,000-year-old grave in a desert cave is the oldest evidence of smelted lead on record in the Levant, a new study finds.

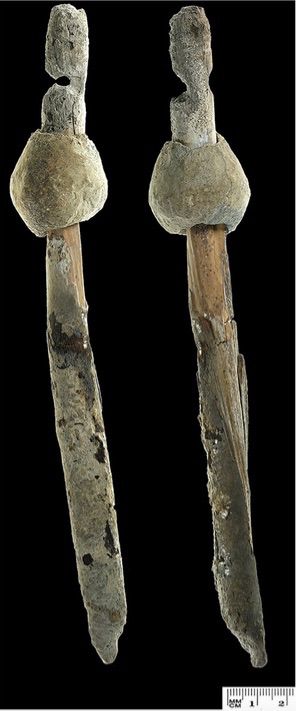

The artifact, which looks like something between an ancient wand and a tiny sword, suggests that people in Israel's northern Negev desert learned how to smelt lead during the Late Chalcolithic, a period known for copper work but not lead work, said Naama Yahalom-Mack, the study's lead researcher and a postdoctoral student of archaeology with a specialty in metallurgy at the Institute of Earth Sciences and the Institute of Archaeology at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

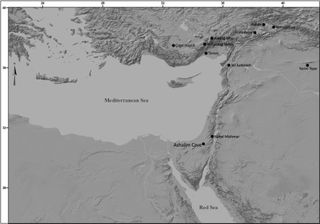

Moreover, an analysis of the lead suggests that it came from Anatolia (in modern-day Turkey), which is part of the Levant, or the area encompassing the eastern Mediterranean. The artifact was likely a valuable tool, given that it shows signs of wear and was placed in a grave alongside the remains of an individual in the cave, she said. [See Photos of Another Ancient Burial in the Southern Levant]

"This is an incredible find," Yahalom-Mack told Live Science. "It's a uniquely preserved object from the late fifth millennium, which includes metal that was brought all the way from Anatolia. It probably had very high significance for the people who were buried with it."

Researchers discovered the artifact in Ashalim Cave, a sprawling underground cavern that's been on archaeologists' radar since the 1970s. In 2012, the Israel Cave Research Center remapped the cave, and called in a team of archaeologists when they discovered artifacts.

Archaeologists Mika Ullman and Uri Davidovich led the archaeological survey and studied the mazelike rooms, including one used for a burial chamber. The chamber was so small and low that they had to get down on their stomachs and wiggle forward to see the secluded space, Yahalom-Mack said.

It was there that they found the lead artifact.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It was just lying there," Yahalom-Mack said. "All they needed to do was pick it up from the surface of the cave."

The artifact is small — a stick of wood attached to a sculpted lead piece. The wood measures 8.8 inches (22.4 centimeters) long, and is made of tamarisk (a group of plants common in the Negev desert, from the genus Tamarix). The lead piece is 1.4 inches (3.7 cm) long and weighs about 5.5 ounces (155 grams), according to the study.

Radiocarbon dating suggests the wood was created between 4300 B.C. and 4000 B.C., "which is extremely early," Yahalom-Mack said. "For a wooden artifact to be preserved [that long] is incredible."

Smelting lead

Lead, a bluish-white and malleable metal, is typically found with other elements — such as zinc, silver and copper — in nature. Lead is rarely found by itself, meaning that metal workers have to smelt it — or heat and extract it from rocks known as ore that contain metals and other minerals.

In fact, smelted lead is unheard of during the Late Chalcolithic, Yahalom-Mack said. During that time, people had figured out how to smelt copper and copper alloys — which is unusual, given that copper is more difficult to smelt than lead because lead can be smelted at lower temperatures.

Lead doesn't tend to occur naturally in the Negev desert, so after discovering the artifact, the researchers studied its isotopes (variations of an element) to determine its origin. An analysis showed that the artifact "was made of almost pure metallic lead, likely smelted from lead ores originating in the Taurus [mountain] range in Anatolia," the researchers wrote in the study. [In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World]

Perhaps the finished artifact was brought from Anatolia, or maybe the raw materials made their way to the southern Levant, where the object was assembled, the researchers said.

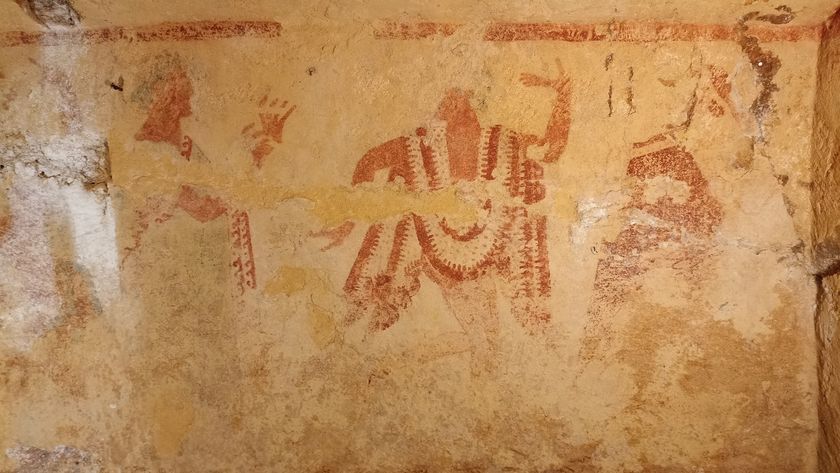

"In this respect, it fits very well with what we know about the Chalcolithic culture, which was a highly developed culture with amazing abilities in art and craft," Yahalom-Mack said. People from the Chalcolithic period also carved ivory and used a sophisticated method known as "lost-wax casting" to fashion metal objects, she said.

Ultimate purpose

How the Late Chalcolithic people used the artifact, however, is anyone's guess.

It could be a mace-head used mostly for ceremonial purposes, as mace-heads (clublike objects) were found at another Late Chalcolithic archaeology site known as Nahal Mishmar, or the Cave of the Treasure, in the southern Levant. But unlike the Nahal Mishmar mace-heads, the newfound artifact is likely not made of cast metal, and it's also smaller, so it may have served another purpose, Yahalom-Mack said.

Another idea is that the artifact is a spindle, with the wooden shaft serving as the spindle rod and the lead object serving as a weight known as a whorl. There are abrasions on the lead that could have been made by spinning, and Dafna Langgut, a co-researcher of the study and the director of the Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Ancient Environments at Tel Aviv University, is investigating this idea.

If the object were a spindle, its whorl would have been slightly heavier than most known whorls (which are typically made of stone), meaning the artifact would have produced only coarse yarn, Yahalom-Mack noted. Because of this discrepancy, the researchers speculate that the artifact was used for some unknown purpose before being repurposed as a spindle whorl, they said in the study.

"Its eventual deposition in the deepest section of Ashalim Cave, in relation to the burial of selected individuals, serves as evidence of the symbolic significance it possessed until the final phase of its biography," the researchers wrote.

Other lead work

There are a few examples of lead work during the Late Chalcolithic, but none has been studied as thoroughly as the new artifact.

For instance, archaeologists have found two lead objects dating to before the fourth millennium B.C. in northern Mesopotamia and eastern Anatolia. But because these objects haven't been examined, it's unknown whether they were smelted or crafted from native lead, Yahalom-Mack said.

However, if these two objects were smelted, it would suggest that ancient people in the Middle East had learned how to smelt lead but that the groups likely learned this skill independently of each other, at around the same time during the Late Chalcolithic, Yahalom-Mack said.

The findings were published online Wednesday (Dec. 2) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.