Death by Flatfish: Whales Suffocate After Soles Clog Blowholes

Two long-finned pilot whales died along the Dutch coast last winter after flatfish got stuck in the whales' blowholes and suffocated the giant mammals, a new study finds.

Blowhole suffocation due to fish is rare, and the researchers called it a "lose-lose situation," because both the whale and the flatfish, which were common sole (Solea solea), died during the event.

"[The whales] were surely feeding on them. It just went wrong," said study lead researcher Lonneke IJsseldijk, a biologist and a faculty member of veterinary medicine at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. "What we think happened is [the soles] were putting up a fight or they became stuck, and both animals died." [Whale Album: Photos Reveal Giants of the Deep]

Long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas) don't typically swim in the southern North Sea, the body of water amidst the United Kingdom, Northern Europe and southern Scandinavia, IJsseldijk said. So people took notice when a pod of 20 to 40 whales was spotted near Norfolk, England, on Nov. 10, 2014.

Three days later, the pod was spotted in the shallow waters off of Belgium's coast, a curious place to venture for the typically deep-water species. In fact, a group of U.K. volunteers raced to prevent a mass stranding when the whales attempted to enter shallow water north of the Thames in Essex on Nov. 18.

A sad sight greeted scientists on Nov. 20, when they found a dead juvenile female stranded in the River Blackwater in Essex. A necropsy (an animal autopsy) showed the animal was "extremely emaciated" and had meningoencephalitis, or swelling in the brain and meninges (special membranes covering the brain).

Pilot whales are highly social animals, and often stay with sick or injured pod members, IJsseldijk said. Perhaps the pod followed the sick female whale to the southern North Sea, IJsseldijk said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, the deep-ocean squid and fish that pilot whales usually eat aren't available in the shallower southern North Sea. So the whales would have dined on other fish, including the common sole, which likely led to the deaths of two whales in that pod, the researchers found.

Asphyxiating on flatfish

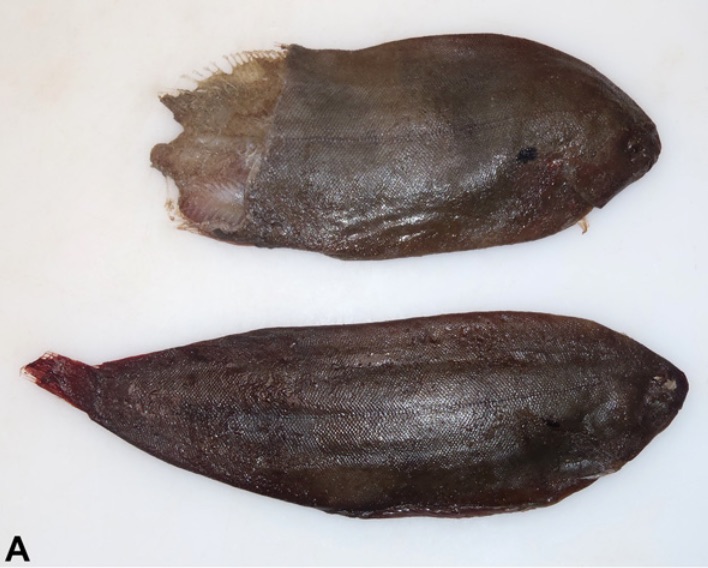

Disaster struck the whale pod in December 2014 and January 2015. Dutch officials found a 12.6-foot-long (3.85 meters) juvenile male and, later, a 14.7-foot-long (4.5 m) adult female dead and stranded on the Netherlands' coast.

The male had a 13.6-inch-long (34.6 centimeters) sole lodged in its blowhole. The female suffered a similar fate, with a 10.8-inch-long (27.5 cm) sole in her blowhole and another in her esophagus, which suggests she was eating them before she died.

It's impossible to definitively say what really killed the whales, as no one saw them die. But a necropsy didn't find any other life-threatening problems with the whales, suggesting they died because of asphyxiation, IJsseldijk said.

The whale's anatomy may explain how this happened. When pilot whales swallow a fish, the prey usually goes to the right or the left of the whales' larynx. But if the prey is large, the whales can disconnect their larynx to create more room to swallow a large, tasty bite. [Marine Marvels: Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures]

If the larynx is dislocated, it's possible for live prey — especially a flexible and feisty common sole — to reach the nasal passage. At this point, the whales likely "coughed," forcing air through the nasal passage to clear it, IJsseldijk said. But that only lodged the sole firmly into the whales' blowholes, she said.

"The fish was too big to get through," she said. "When I found the fish [during the necropsy], it was really stuck. I had to force it out."

The only other recorded instance of a Globicephala species asphyxiating due to a fish dates to 1581, when a pilot whale was stranded in the Netherlands after it "suffocated on a salmon," according to the more than 400-year-old report.

However, harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) as well as bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) are known to suffocate on fish that get into those animals' nasal passages, IJsseldijk said.

The finding is alarming because if other whales leave their natural habitats — to accompany an ill pod-member, escape noise pollution or respond to climate change — a pod could end up in an area with unfamiliar prey that could ultimately suffocate them, she said.

"Animals do make mistakes, just like humans do," said Robin Baird, a research biologist at Cascadia Research Collective, a scientific and education nonprofit based in Olympia, Washington, who was not involved in the study.

"Pilot whales are deep-water animals, and they're not typically found on the continental shelf," Baird said. "I think having them come into shallow waters, for whatever reason, put them in a situation that [meant] they were feeding on things that they wouldn't normally feed on, and obviously, the unintended consequences of that."

The study was published online Nov. 18 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.