Ancient Whales Gave Birth on Land

More than 47 million years ago, a whale was about to give birth to her young … on land. That's according to skeletal remains of a pregnant cetacean whose fetus was positioned head-down as is the case for land mammals but not aquatic whales.

The teeth of the fetus were so well-developed that researchers who analyzed the fossils think the baby would have been born within days, had its mom not died.

The fossil discovery marks the first extinct whale and fetus combination known to date, shedding light on the lifestyle of ancient whales as they made the transition from land to sea during the Eocene Epoch (between 54.8 million and 33.7 million years ago).

Philip Gingerich, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his team discovered the pregnant whale remains in Pakistan in 2000, and then in 2004, Gingerich's co-authors and others found the nearly complete skeleton of an adult male from the same species in those fossil beds. The adult whales are each about 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) long and weighed between 615 and 860 pounds (280 and 390 kg), though the male was slightly longer and heavier than the female.

(Gingerich is also director of the University of Michigan's Museum of Paleontology.)

{{ video="LS_090204_whale" title="Surprising Whale Discovery" caption="Remains of a mother whale with her fetus inside were discovered. " }}

Confusing find

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On the dig that ultimately yielded the pregnant whale, Gingerich and his team first spotted what looked like a line of chalk on the ground surface, which later turned out to be the teeth of the whale fetus.

"Very quickly I got into the baby's teeth," Gingerich told LiveScience. "Then I kept going around it, and the ribs seemed too big for the size of the animal and they were all going the wrong way. So I have to say I spent the whole day excavating this thing confused about what in the world was going on here."

Soon after, Gingeric discovered another, larger, skull, and he realized the fetus was still inside its mother.

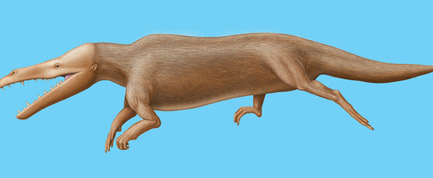

The new species, now called Maiacetus inuus, is a member of the Archaeoceti, a group of cetaceans (an animal group that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises) that predate modern toothed and baleen whales. Archaeocetes had mouths full of several types of teeth, as well as nostrils near the nose tip. Both features are seen in land mammals but not in today's whales.

Like other archaeocetes, the newly discovered whale was equipped with four legs modified for foot-powered swimming (sort of like climbing, or scrambling, up a steep hill but instead in water). While the whales likely could support their weight on their flipper-like limbs, they probably couldn't go far on land.

"They clearly were tied to the shore," Gingerich said. "They were living at the land-sea interface and going back and forth."

Land delivery

The team suggests that Maiacetus fed at sea and came ashore to rest, mate and give birth.

The head-first position of the fetus matches what is found in many land animals, particularly the artiodactyls (pigs, deer and cows), which are thought to have given rise to ancient whales. Human babies also emerge head first, ideally.

Scientists speculate that a head-first orientation allows land mammals to breathe even if they get stuck in the birth canal.

That's not the case underwater. "If you're born in the water you don't want the head out away from the mother until it's going to pop free, because you don't want it to drown,” Gingerich said.

In addition, tail-first delivery in modern whales and dolphins would ensure the baby is facing in the same direction as its mother who is likely swimming. To keep mom and baby from getting separated, tail-first delivery would be optimal, Gingerich said.

The research, published in the Feb. 4 issue of the online journal PloS ONE, was funded by the Geological Survey of Pakistan, National Geographic Society, National Science Foundation and Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

- Video - Surprising Whale Discovery

- Whale News, Information and Images

- Early Whales Had Legs

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.