A hidden portrait lying beneath Leonardo da Vinci's most famous painting may depict the real "Mona Lisa," at least if one man's theory is correct.

Reflected light waves from the painting have revealed four different phases, or images, beneath the surface of "La Gioconda." The third of these images is a woman who looks very different from the one now known as "Mona Lisa." This, in fact, may be the real Lisa, the woman that da Vinci was commissioned to paint in 1503, said Pascal Cotte, the founder of Lumiere Technologies, who announced his findings on Tuesday (Dec. 9) at a news conference in Shanghai.

"It is the portrait of Lisa Gherardini," Cotte said.

If so, that means the identity of the most famous woman in the world is a mystery.

But not everyone is convinced of Cotte's interpretation. The findings have not been submitted to a peer-reviewed journal, the standard process for vetting scientific results. And it's taking a big leap to say that beneath the "Mona Lisa's" additional layers of paint is a complete image of a different person, experts said. [25 Secrets of Mona Lisa Revealed]

Most famous girl in the world

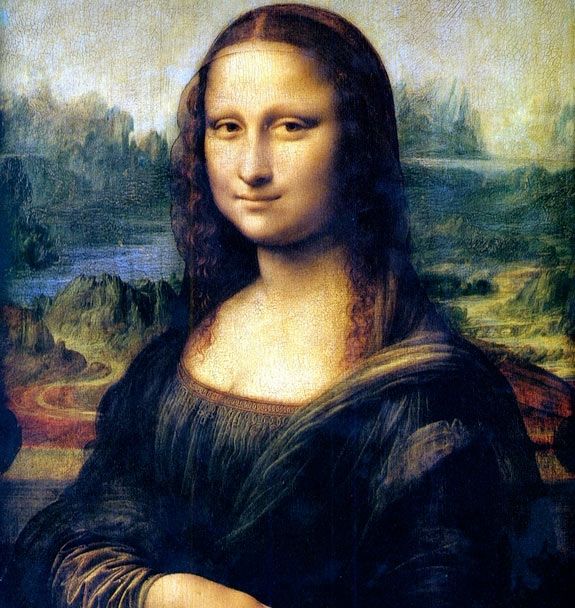

The "Mona Lisa" is known for its subject's enigmatic half-smile and the way her eyes seem to follow a viewer as he or she moves. Most experts believe the subject is Lisa Gherardini, the wife of the wealthy silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo. Da Vinci received the commission in 1503 in Florence, Italy, and historians believe it was completed by 1506. [Lost Art: Paintings Stolen from the Gardner Museum]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The mysterious woman, who seems to hide a million secrets behind those cryptic eyes, has spawned endless speculation over the years. Some have argued that the "Mona Lisa" is actually a self-portrait of da Vinci in a woman's dress, while others claimed the painting hides microscopic codes. And in 2014, scientists said the master made two paintings, one on top of the other, to create a kind of stereoscopic, 3D "Mona Lisa."

Hidden girl

Cotte has spent 10 years analyzing La Gioconda using a special technique he devised. In it, a camera shines light in many different wavelengths on the painting, then uses the Fourier transform, a mainstay mathematical technique used in signal processing, to analyze the waves that reflect back.

The different pigments and binders in each color of paint absorb, reflect and scatter different amounts of light at different wavelengths. So Cotte analyzed 3 billion pieces of data to recreate the images beneath.

He found four separate phases of painting beneath the most famous painting. The first painting on the wood seems to be a rough outline of the portrait, in which the sleeves, the chair and the head size are different from the surface painting that everyone sees, Cotte said. The second layer from the bottom seems to show hairpins and a headdress or veil decked out with pearls.

"Some hairpins are visible with the naked eye," Cotte told Live Science. "You go today to the Louvre to look and you will see the hairpins in the sky."

But the third layer is where things get interesting. That, he says, depicts a totally different woman, one with a slimmer face that is facing off to the side (as was fashionable in portraits at the time) and a dress that matched the fashions of Florence in 1503, when del Giocondo commissioned the painting. To Cotte, that is evidence that this third, hidden painting is in fact Lisa Gherardini.

Cotte said he is not an art historian, so he doesn't want to speculate on why da Vinci would have painted over the real Mona Lisa without delivering it to del Giocondo. He also doesn't know why da Vinci would choose to repaint the image rather than starting from scratch on a new piece of wood, although it could have saved the trouble of repainting the sky and background, he said. In addition, the light analysis doesn't reveal when each layer was laid down, meaning the third and the fourth layers could have been painted 10 years apart, or just a few months or days apart, Cotte said.

Either way, if the real Lisa is beneath the surface, then who is the "Mona Lisa?"

"This is not my job to tell you that this is a Madonna or this is a saint or this is an allegory of justice," Cotte said.

Hidden portrait or ordinary artistic process?

However, several experts are skeptical about the new results.

"A different outward appearance does not lead 100 percent into a hypothesis that these are two different persons," said Claus-Christian Carbon, a researcher at the University of Bamberg in Germany, who published the work on a stereoscopic "Mona Lisa." " I'm quite skeptical, because the minimal hypothesis is always the best I think, and that is just that [the portrait] was changed a bit."

For instance, even though scientists often say humans are "face experts," that only applies to people we are acquainted with. It's extremely difficult for a person to look at two pictures of an unfamiliar person and say they are the same person, a slightly different person, or a totally unrelated person, Carbon, who was not involved in the new research, told Live Science. That proves even more difficult if they are facing in different directions, he added.

And though Cotte has developed "a terrifically powerful technique" to analyze the painting, its interpretation is up for debate, said Martin Kemp, a professor emeritus at the University of Oxford, who has spent his life studying da Vinci's work.

Beyond that, the idea that da Vinci reworked the painting in sharp phases separated in time isn't consistent with the Renaissance man's style, said Kemp, who has collaborated with Cotte before but was not involved in the current research.

"Leonardo was very restless, he was always changing his mind," Kemp told Live Science. Thus, it's more likely that he reworked the painting with small changes and corrections in a more fluid evolution, rather than in sharply delineated phases.

It's common, for instance, for artists to paint over their work if they or their sitters are not happy with it or they just feel it needs reworking, Kemp said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.