While U.S. in Big Chill, Arctic Runs Fever

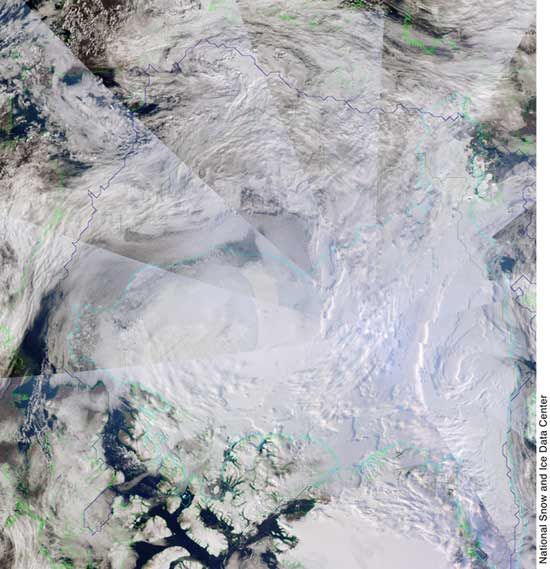

While parts of North America have been in the icy grips of an unusually cold and snowy winter recently, the Arctic has been downright balmy compared to past winters. These warmer-than-normal temperatures mean that the sea ice in the Arctic is looking pretty anemic, despite the winter season. Arctic ice goes through a normal cycle of summer thaw and winter re-freeze. In recent decades, however, sea ice has become overall less extensive and thinner, leading to forecasts that in future decades the polar region will be ice-free during summer. The trend looks to be continuing this winter, scientists now say. Warmer Arctic Climate swings in any single season are part of Nature, of course. That's why records — warm or cold, wet or dry — get broken. For much of the United States, this winter has been an exceptionally chilly one. The average temperature for the United States in December, 32.5 F, was almost 1 degree Fahrenheit below the average for the 20th century, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Much of the West and Midwest had a particularly frigid month, with temperatures plunging several degrees below average. This winter in the Arctic has been a completely different story. "It's warm everywhere in the Arctic. It's anomalously warm," said Julienne Stroeve, of the National Snow & Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colo. Both December and January have been abnormally warm months, which impacts the cyclical re-freezing of sea ice over the years, because these are "two crucial ice-growing months," Stroeve told LiveScience. Thinner ice, more melt Arctic sea ice hasn't been reaching its former thicknesses and extents in recent years, especially after the dramatic meltdown observed in the summer of 2007, which opened up the fabled Northwest Passage. (This past summer saw the second lowest summer ice area on record.) That record melting — which left 30 percent less ice in the Arctic than there was at the previous record low — caused the loss of substantial amounts of older ice, which is thicker and generally survives the summer. Older, thicker ice is typically 6.5 to 10 feet (2 to 3 meters) thick, while younger ice is closer to 3 feet (1 meter) in thickness. Melting exposes more areas of open ocean, which absorbs incoming sunlight that the ice would normally reflect, so there is the potential for a snowball effect, or what scientists call self-reinforcing or feedback. Come winter, the ice that refreezes is thinner, first-year ice, which is more susceptible to melt in the summer, potentially exposing even more open ocean. "That [thinner ice] typically can all melt out in the summer," Stroeve said. This year, the future That feedback seems to be kicking in, as now "the Arctic is just more dominated by that thinner ice," Stroeve said, adding that unless February and March are much colder than normal, this winter's ice could end up covering less area than normal and be thinner than even in recent years. So far, this winter has been warmer than last, Stroeve said, and some odd weather patterns cropped up in both December and January that brought ice growth to a standstill. Pauses in the regrowth of ice aren't a new phenomenon — they have happened before, even in much colder winters — but they only exacerbate the current situation in the Arctic by adding yet another mechanism that stagnates ice growth. In January, these weather patterns created different conditions in different parts of the Arctic. While ice grew southwest of Greenland, it retreated in areas east of Greenland and in parts of the Barents Sea, the NSIDC reported. While ice is still re-freezing, ice coverage area at the end of January was still 293,000 square miles (760,000 square kilometers) less than the 1979-2000 average, according to the NSIDC. This didn't break the record low for January ice area (set in 2006), but it put January 2009 in the top six. Including this year, January ice area is declining by about 3 percent per decade, the NSIDC reported. Looking further into the future, unless there are several very cold winters and mild summers, Arctic sea ice is unlikely to bounce back in the coming decades. "The idea of recovery right now seems pretty slim," Stroeve said. "You just don't get very cold temperatures like you used to." Eventually, the sea ice is expected to melt out entirely in the summer, leaving only a cover of winter seasonal ice. The NSIDC predicts that this will happen around 2030, though Stroeve says it could happen earlier, as indeed some other scientists predict. That it will happen seems fairly certain: "There's no doubt in my mind about that," Stroeve said.

- Video – Melting Sea Ice Seen From Orbit

- Quiz: Global Weather Extremes

- Arctic News and Information

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.