Diet and Weight Loss: The Best Ways to Eat

Low carb, or low fat? Should you go Atkins, Zone or Paleo? Or does it even matter which diet you choose when you want to lose weight? Most weight loss experts say that shedding pounds comes down to a simple formula: calories in versus calories out. In other words, if you burn more calories than you take in, you'll lose weight.

However, the question of exactly how to cut calories — in a healthy, sustainable way — has often perplexed dieters. To find the best diets for weight loss, Live Science conducted a months-long search for information. We spoke with many weight loss experts and dove deep into the most well-regarded studies on the topic done to date. We wanted to know what these studies found and, ultimately, determine the best approaches to healthy eating for weight loss.

We found that the calorie equation reigns supreme as the most important aspect of losing weight, but also that there's still plenty of room to choose a diet that fits your personal preferences. For example, Dr. Frank Hu, a professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told Live Science that "the No. 1 factor is still a calorie deficit, so the question is, what kind of styles or what kind of foods can help people achieve a calorie deficit, and what can sustain the calorie deficit?" [What Are Calories?]

(What all experts did not agree on, however, was the calorie question: Is a calorie really a calorie?) [The Great Calorie Debate]

So, what should you eat if you're trying to slim down?

"The best food someone on a diet should eat? The same foods they should eat when they're not on a diet, but just less of them," said Dr. Frank Sacks, a professor of cardiovascular disease prevention, also at Harvard's School of Public Health. All of the experts we spoke with agreed that those foods should include the staples of a "healthy" diet — fruits, vegetables, whole grains and healthy fats. These foods are important not only for achieving or maintaining a healthy body weight but also for good health in general.

In this article, we'll highlight some of the most popular diets people turn to in order to lose weight, and explain what the science really says about how well they work. But before we delve into the diets, it's important to break down the macronutrients of the foods we eat — carbohydrates, fats and protein — and the roles they play in the body. Of course, individual food can contain more than one more macronutrient.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Back to basics

Carbohydrates

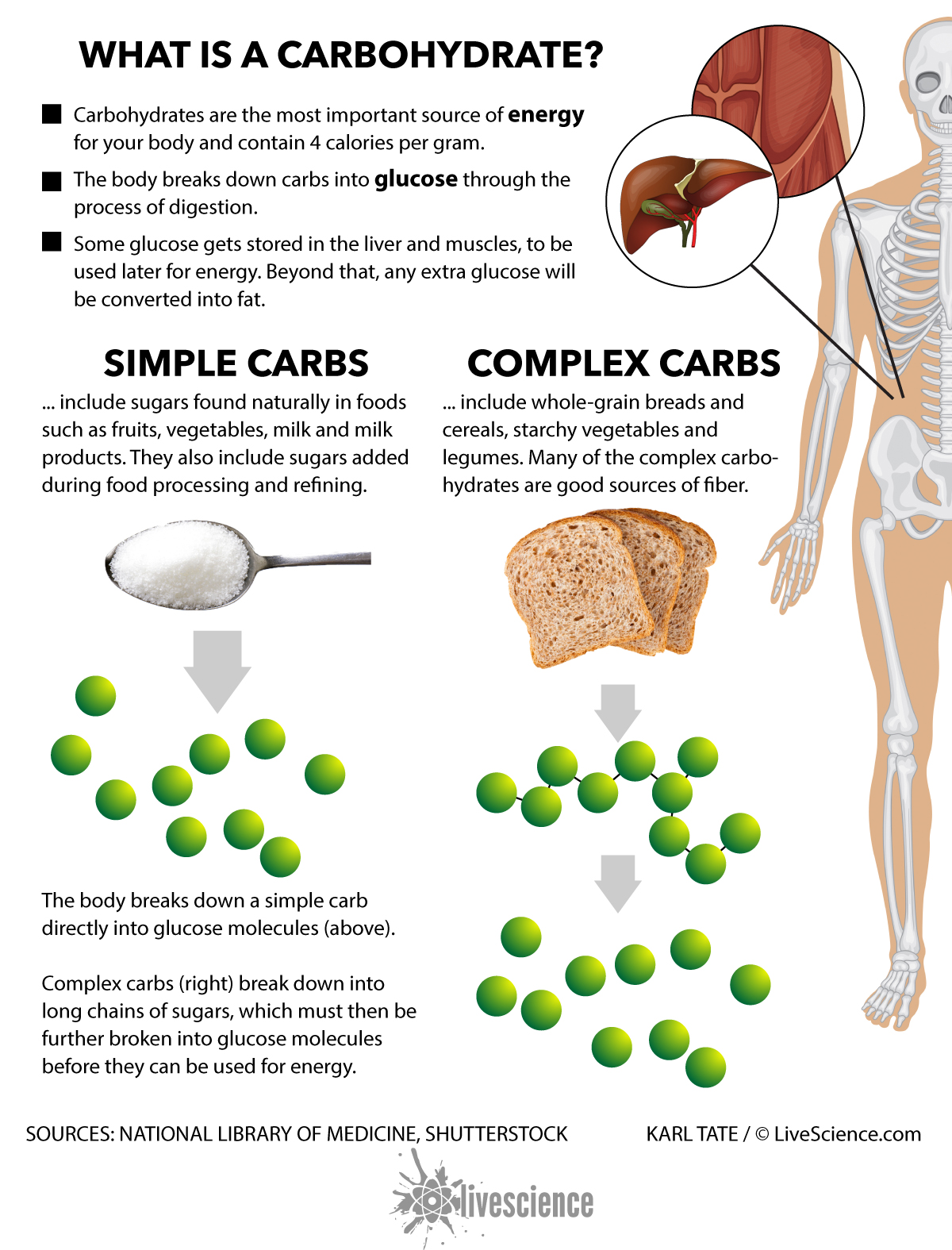

Carbohydrates are your body's go-to source of energy, and they're digested quickly. Glucose — the most basic unit of a carbohydrate — is the only type of carb your cells can use directly to make energy. But the carbs we eat come in three forms — sugars, starches and fiber — and when it comes to weight loss, these three are not equal. [What Are Carbohydrates?]

Sugars (found in fruit, vegetables and dairy) and starches (found in grains, vegetables and beans) ultimately suffer the same fate: They're broken down into glucose and are used by the body for energy. But your body can use only so much energy at once, so not all of the glucose you eat is immediately used for fuel. Some of the extra glucose can be stored in your liver or muscles and be used later.

As for the rest? It gets converted to fat.

The difference between sugars and starches — which are sometimes referred to as "simple" and "complex" carbohydrates, respectively — is the complexity of their structure. Sugarscontain only one or two molecules, so it's very easy for the body to digest sugars and absorb them into the blood. Starches, in contrast, contain many simple carbohydrate molecules linked together. Because of their size and complexity, starches take longer to be digested into single molecules.

Fiber is an entirely different ball game. Fiber is found alongside sugars and starches in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes. Like starch, it's a complex carbohydrate, meaning it contains many carbohydrate molecules linked together. However, your body can't digest fiber, so this carbohydrate doesn't get absorbed by the gut. It never enters the bloodstream, and it is never broken down for energy. The stuff passes through your body relatively untouched.

The benefit of eating starches, and especially fiber, rather than sugars is that they can help you feel fuller for a longer time because they are either broken down slowly or aren't broken down at all. And the idea is, if you're feeling full, you'll eat less. Of course, keep in mind that complex carbs aren't a free pass to eat as much as you like — extra calories consumed will still be stored as fat.

Compared with fat, carbohydrates are less calorie-dense: 1 gram of carbohydrates contains 4 calories, whereas a gram of fat contains 9 calories. However, because carbohydrates are broken down and absorbed quickly, they can lead to a quicker burst of sugar into the bloodstream than fat does. Therefore, carbs may raise blood sugar levels more than fat does (when compared in equal amounts).

Proteins

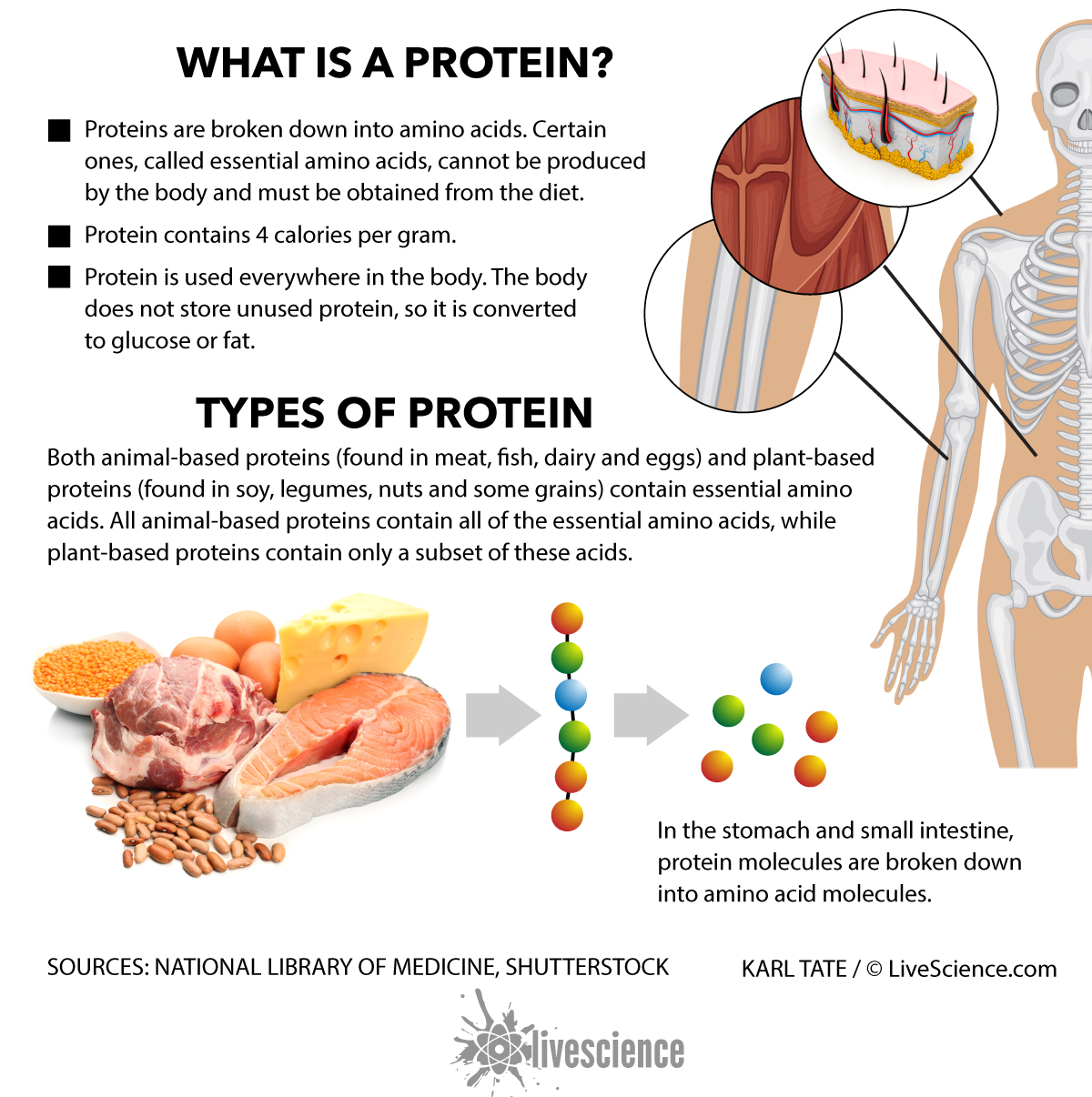

Protein-rich foods are important for everyone, not just bodybuilders. Protein serves as the building blocks for our bodies, from the tiniest structures inside our cells, to the largest parts of our anatomy. Unlike carbs or fat, excess protein isn't readily stored by the body, so it's essential to eat enough of this macronutrient every day. Of course, just because your body doesn't store the protein doesn't mean you have free rein to eat as much as you'd like without gaining weight. The body can convert excess protein into glucose, or store it as fat. [What is Protein?]

When you eat protein, the large protein molecules are broken down into their basic components, which are known as amino acids. There are 20 amino acids that are important in the body, and some can be converted from one type of amino acid to another as needed. However, there are also several amino acids that cannot be produced in the body by converting other amino acids, meaning you must get these amino acids from your diet. These are known as essential amino acids.

Both animal-based proteins (such as those found in meat, fish, dairy and eggs) and plant-based proteins (found in soy, legumes, nuts and some grains) contain essential amino acids. However, whereas all animal-based proteins contain all of the essential amino acids your body needs, plant-based proteins generally contain a smaller set of amino acids. That means that if you eat a vegan diet, you need to eat a variety of plant types to get all of your essential amino acids.

As with carbohydrates, 1 gram of protein contains 4 calories.

Fats

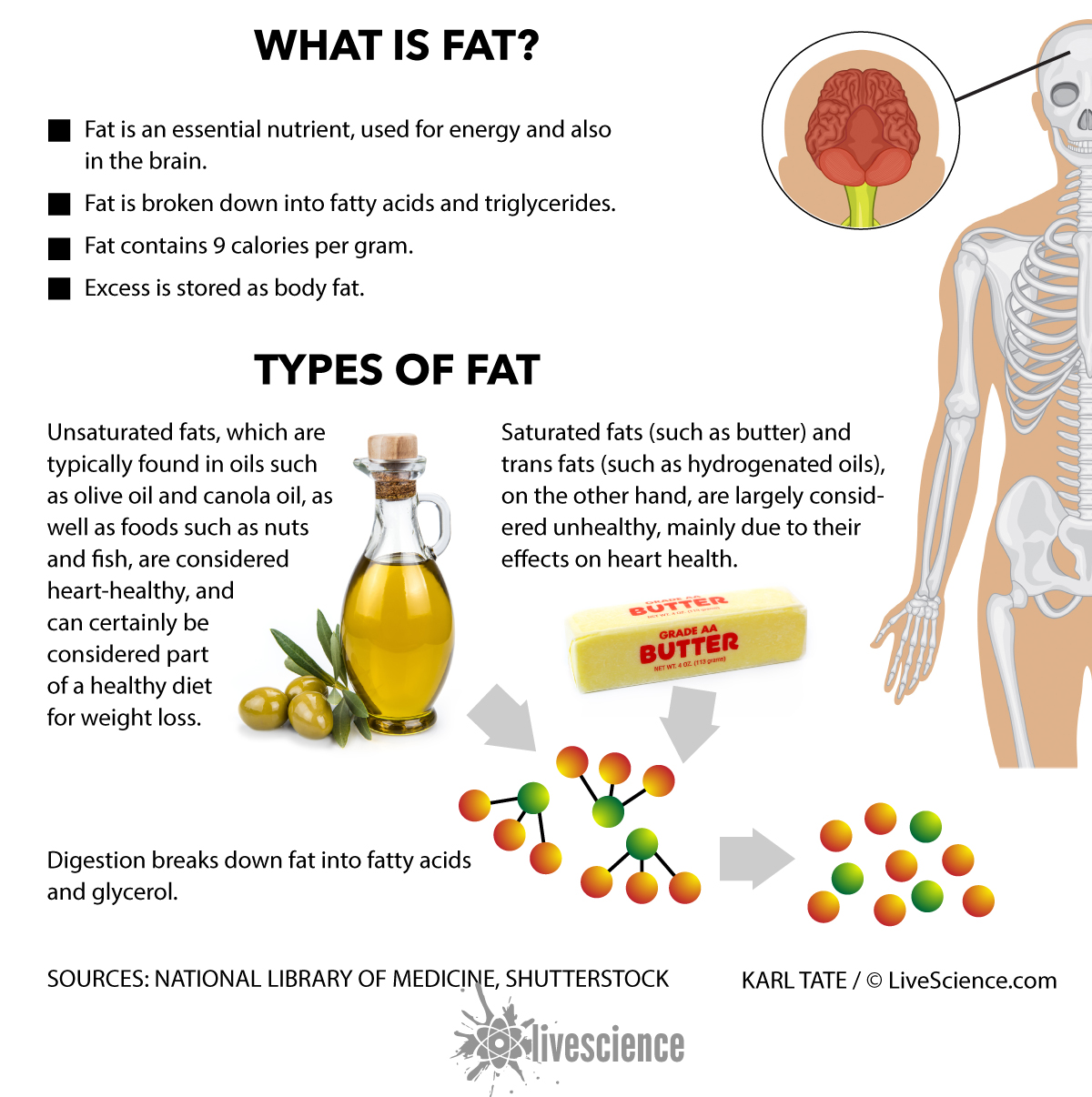

Fat does more than pad your waistline — in fact, your body needs some fat to function. For example, in addition to being a reserve source of energy that can be taken out of storage and converted into glucose if needed, fat can help your body absorb certain vitamins. And because fat is broken down more slowly than carbs, it can also help you feel full longer than carbs can.

But there's no doubt that fat is high in calories. In fact, it's the most calorie-dense of the macronutrients, weighing in at 9 calories per gram.

Of course, like carbs, not all fats are created equal. Unsaturated fats are typically found in fats that are liquids at room temperature — oils such as olive oil and canola oil — as well as foods such as nuts and fish. These fats are considered heart healthy, and can certainly be considered a part of a healthy diet for weight loss.

But saturated fats (such as butter), which are usually solid at room temperature, and trans fats (such as hydrogenated oils) are largely considered unhealthy, mainly because of their effects on heart health.

Fat that goes unused by the body ultimately has the same fate as carbs and protein: It's stored as fat.

The macronutrient wars

Though all three macronutrients — carbs, protein and fat — are essential to your diet, there's debate about exactly how much of each you should eat. Should carbs be the star of your diet, and fat be consumed sparingly? Or should fat be fronted-loaded? Or do the relative amounts of macronutrients in your diet even matter at all?

There's an abundance of advice in books, magazines and online sources about the best way to diet, and there are anecdotes about the diet "trick" that worked miraculously for someone's mom's best friend's former next-door neighbor to be found everywhere. But how do we know if they actually work?

Enter clinical trials, which allow researchers to directly compare the effects of different diets. And even among these trials, some are better designed than others. Researchers consider many factors when looking at the quality of a trial, including the size of the trial (the more participants, the better) and the length of the study period (the longer, the better), when deciding how much stock to put into the results.

The largest clinical trial that compared different diets was the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Dietary Modification Trial, which included more than 48,000 postmenopausal women and had a follow-up period of seven years. However, the trial was not designed to look at weight loss. Rather, the goal of the trial was to see how fat in the diet affected the women's risk of cancer and heart disease. (Because the trial was only in women, it's unclear if the results also apply to men.)

The WHI Dietary Modification Trial was designed in 1990, when researchers were asking many questions about whether high-fat diets or low-fat diets were better for people's health, said Barbara Howard, a senior scientist at the Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington D.C. In a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 2006, Howard took data from the original WHI Dietary Modification Trial and looked to see whether the two diets had different effects on weight loss.

In the WHI, 40 percent of the participants were encouraged to reduce their fat intake so that only 20 percent of their total daily calories came from fat. (At the study's start, all of the participants had reported that at least 32 percent of their daily calories had come from fat.) The women were encouraged to increase their daily servings of fruits, vegetables and whole grains, and attended group sessions where they got advice about cutting fat. However, because the trial wasn't designed with weight loss in mind, these women were not encouraged to cut calories.

The other 60 percent of the women went into the control group. They were given a copy of the U.S. government's Dietary Guidelines for Americans and some additional educational material, but that was it. [Low-Fat Diet: Facts, Benefits & Risks]

The researchers monitored the diets of all of the participants during the study through questionnaires, and measured the women's height and weight at annual checkups.

It turned out that the women in the low-fat-diet group lost a little bit of weight over the course of the study period, and they maintained their weight loss, said Howard, who is also a scientist at the MedStar Research Institute, a non-profit healthcare system of hospitals and clinics in the Washington D.C. area.

The researchers found that the women in the low-fat-diet group lost about 5 lbs. (2.2 kilograms) during the first year of the study, and then maintained a lower average weight than the control group over the rest of the study period.

The researchers concluded that there was a "clear relationship" between the change in the women's fat intake and their weight, they wrote in their study. The questionnaires showed that the women in the low-fat-diet group increased their daily intake of fiber, fruits, vegetables and whole grains, and decreased their daily intake of total fat, saturated fat and unsaturated fat. [Which States Are Eating Their Fruits and Veggies?]

In particular, the women who cut the most fat lost the most weight, the researchers found.

Also, the women in the low-fat-diet group who ate more fruits and vegetables also lost more weight than those whoate smaller amounts of fruits and vegetables, the researchers found. The same went for fiber: The women who ate more fiber lost more weight than the women who ate less fiber.

Another long-running clinical trial designed to compare the effects of different diets on weight loss was carried out in Israel: the Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial, or DIRECT, study.

But although that large, high-quality study found a relationship between a low-fat diet and weight loss, other studies conducted since have found that a low-fat diet is no more effective than other types of diets in helping people lose weight. It's important to note that the women in the study who switched to a low-fat diet didn't replace the fat in their diet with white bread and other refined carbohydrates, Howard said. In other observational studies, researchers have shown that when "high-carb" means sugar and refined carbohydrates, people don't lose weight, she noted.

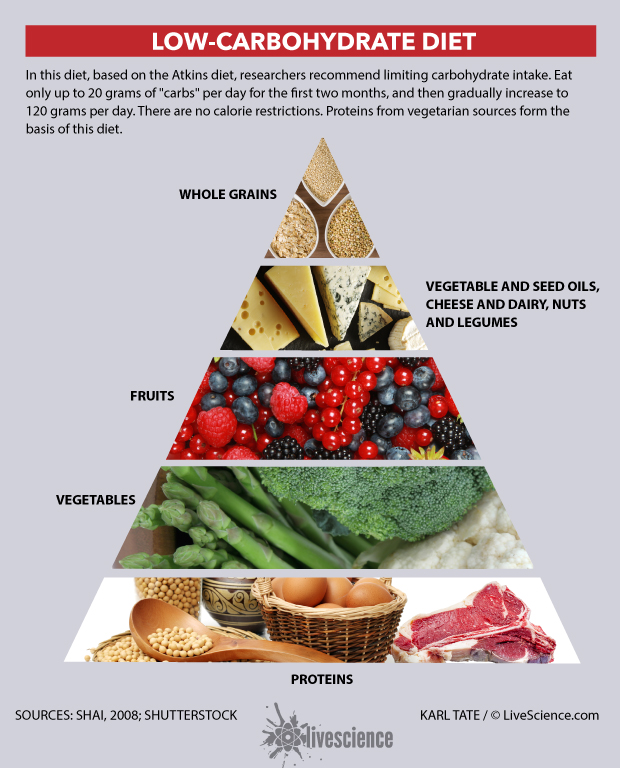

The trial included 322 people, ages 40 to 65, all of whom were overweight and worked at the same research center. The participants were randomly assigned to different diets — a low-fat diet, a Mediterranean diet or a low-carb diet — for a two-year period. The researchers also conducted a follow-up four years after that, so the total study period was six years. The participants in the low-fat diet group and the Mediterranean-diet group were instructed to cut their calories, while those on the low-carb diet were given no calorie restrictions.

As in the WHI study, the participants received diet guidance in small group sessions. (One key difference between the two studies, however, was that in the DIRECT study, everyone was assigned to a group session.) In addition, because all of the participants worked at the same place, the researchers provided lunch each day. Each diet group was given a lunch that fit their diet, according to the report of the study, published in 2008 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

But unlike in the WHI study, the low-fat diet in the DIRECT study didn't result in the most weight loss. Rather, weight loss was the highest in the low-carb group — the participants in this group lost an average of 12.1 lbs. (5.5 kg) after two years. The participants in the Mediterranean-diet group lost, on average, 10.1 lbs. (4.6 kg), and the participants in the low-fat group lost, on average, 7.3 lbs. (3.3 kg) after two years. [Low-Carb Diet: Facts, Benefits & Risks]

Additionally, there was a difference in which diets were the most effective for each sex. The women in the study who were on the Mediterranean diet lost more weight than the women on the low-fat diet. In comparison, the men on the low-carb diet lost more weight than the men on the low-fat diet, the researchers found. (However, only 45 women completed the study, compared with 277 men.) In other words, both women and men lost more weight on a diet other than the low-fat diet.

The DIRECT study showed that one diet doesn't fit all, said Iris Shai, a professor of nutrition and epidemiology at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel and the lead author of the study. In other words, the researchers learned that there are some alternatives to a low-fat diet that also work for weight loss, Shai told Live Science. These alternatives (the low-carb diet and the Mediterranean diet) also have more health advantages in the long run, such as improved cholesterol and blood sugar levels, respectively, she said.

However, Shai noted that even though the people on the low-carb diet were not given a calorie restriction, they ended up eating a similar number of calories as the people in the calorie-restricted groups, Shai said. Ultimately, all of the groups cut their calories by about 400 to 500 calories a day, she said. In other words, the study suggested that calories do matter for weight loss.

In the follow-up four years later, the researchers found that all of the participants had regained some of the weight. Over the entire six-year period, the average total weight loss was 6.8 lbs. (3.1 kg) for the Mediterranean-diet group and 3.7 lbs. (1.7 kg) for the low-carbohydrate group. The average weight loss of 1.3 lbs. (0.6 kg) for the low-fat group was not statistically significant, meaning that the finding could have been due to chance, the researchers wrote.

One reason the Mediterranean diet appeared to be the most effective for weight maintenance is that, simply put, in real life, a more "balanced" diet that offers many options may work best in the long term, Shai said. [Mediterranean Diet: Foods, Benefits & Risks]

Dr. George Bray, a professor emeritus at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University and the founder of The Obesity Society, agreed.

"I'm a fan of using a high-quality, good-pattern diet with lower amounts of food, and one way of doing that is with portion control," Bray said. Plenty of evidence suggests the Mediterranean diet is highly beneficial for people's health and, combined with portion control, is a good strategy for weight loss, Bray told Live Science. The DASH diet, which was developed to lower blood pressure, also has shown weight loss benefits, he said. The DASH diet is a low-sodium diet that's rich in fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, nuts, beans and seeds.

"As far as I can see, nothing else is of value," Bray told Live Science. "It comes down to calories — pure and simple." [Best Calorie Counter App]

Bray was one of the authors on another major weight loss study, called the Preventing Overweight Using Novel Dietary Strategies study, or the POUNDS Lost study. The results of that study were published in 2009 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

In that study, two teams of researchers — one in Boston and one in Baton Rouge, Louisiana — carried out the randomized trial, which was — and still is — the largest clinical trial designed to compare the weight loss effects of different diets. (The study had more participants than the DIRECT study, although the study period for the POUNDS Lost study was shorter.)

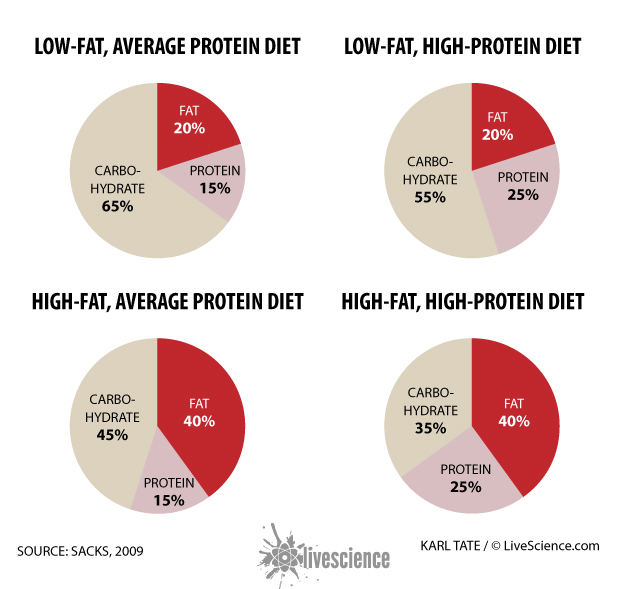

The POUNDS Lost study began with more than 800 participants (400 in Boston, and 400 in Baton Rouge) who were randomly assigned to one of four diets: low-fat with average protein, low-fat with high protein, high-fat with average protein and high-fat with high protein. A total of 645 people completed the study.

The people in the study were assigned to counseling sessions to learn about their diets, and there were group sessions held throughout the course of the study. The researchers provided the participants with daily meal plans, and the plans were largely similar across the four diets, with only small tweaks — for example, to include a bit of extra olive oil, or a bit less meat. All of the diets in the study were healthy — they all contained healthy fats, whole grains, fruits and vegetables, said Sacks, who was the lead author of the study. And all of the diets contained an equal number of calories — fewer than the number of calories the people in the study were normally eating, he said. [2016 Best Food Scales]

So, how did the different diets stack up for weight loss?

The main takeaway of the study is that all of the diets produced the same amount of weight loss, Sacks said. "There was no advantage of one diet type over another," he said. The researchers observed that, at six months, the participants in each diet had lost, on average, 13.2 lbs. (6 kg). After the one-year mark, on average, the participants began to regain some of their weight. By the end of the study, the average weight loss for all of the diets was 8.8 lbs. (4 kg).

Bray, who ran the Baton Rouge arm of the study, noted that there was certainly a range for the weight loss observed among the people on each diet. However, the range was similar in all of the groups, he said. Some people on each diet lost as much as 33.1 lbs. (15 kg), and some people on each diet gained a bit of weight, Bray told Live Science. But even the proportions of people losing a lot of weight or gaining a little weight were similar in all four diets, he said.

The biggest factor for weight loss? Undoubtedly, it was adherence to the diet, Bray said. "If you stuck to [the diet] well, you should lose more, and if you didn't stick to [the diet], you shouldn't," Bray said.

Putting it all together: Meta-analyses

Of course, it's important to keep in mind that, while these three trials have revealed some of the best evidence yet about weight loss strategies, countless smaller or shorter clinical trials have focused on diet and weight loss. To truly get a sense of the state of the field of research, scientists look at many studies together, in a type of study called a meta-analysis. This type of research can be especially valuable when looking at a number of smaller clinical trials because it reveals what the studies show when they are combined as a whole.

A meta-analysis lets researchers examine a large number of smaller studies to see if, collectively, there's been an impact, Bray said. And when you do that with weight loss trials, you don't come out with any notable differences between diets, he said.

A 2014 meta-analysis, published in JAMA, looked specifically at named diets — for example, the Atkins diet, the Ornish diet and others — and found that both low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets resulted in weight loss. There were 48 studies included in the meta-analysis, and between the individual named diets, the differences in weight loss were small, according to the researchers.

Both low-fat diets and low-carb diets resulted in about 18 lbs. (8 kg) of weight loss after six months, according to the study.

And while there were some statistically significant differences in weight loss between some of the diets (for example, after six months, the Atkins diet was associated with a 3.7-lb. (1.7 kg) greater weight loss than the Zone diet), "these differences are small and likely to be unimportant to many seeking to lose weight," the researchers wrote in their study. [2016 Best Online Diet Services]

"The main takeaway [of the meta-analysis] is that there's really no important differences between any of the diets," said Bradley Johnston, the director of Systematic Overviews through advancing Research Technology at the SickKids Research Institute in Toronto and lead author of the meta-analysis.

Indeed, most of the diets that Johnston looked at seemed to come back to calories.

Whether people did low-carb or some other type of diet, most of them were calorie-restricted, Johnston told Live Science. "If you actually follow the diet, it's highly likely that you're going to lose weight," he said.

What's important is that people choose a diet that they can stick with.

"Adherence is crucial," Johnston told Live Science. Because different people have an easier time sticking to different diets, the ideal diet is the one that the individual can adhere to best, so that they can stay on the diet as long as possible, the researchers wrote in their study. And in smaller studies, healthy eating habits have been linked with not only weight loss but also improved health, such as lower blood pressure, lower cholesterol levels, lower blood sugar levels and even improved cognitive function.

In another meta-analysis, published in October 2015 in the journal The Lancet, researchers concluded that low-fat diets were no better than other types of diets evaulated for long-term weight loss. The researchers looked at 53 studies that had weight loss as a goal, as well as other studies for which weight loss was not the primary goal (think back to the Women's Health Initiative study, for example).

When comparing weight loss trials specifically to one another, the researchers found that low-carbohydrate diets resulted in greater weight loss than low-fat diets. For both the weight loss trials and the other trials, the researchers found that higher-fat diets resulted in greater weight loss than low-fat diets. And low-fat diets only resulted in greater weight loss when compared with a person's usual diet, according to the study.

But none of the diets blew the others out of the water. The big picture that people can take away from this meta-analysis is that a low-fat, high-carb diet is not more effective than any other weight-loss diet, said Hu, who was the senior author of the study.

And the amount of weight loss induced by any of the diets was not very impressive, Hu added. Most people regained the weight they lost in six months to a year, he said. Studies have shown that many people tend to regain lost weight over time, and experts think that more research is needed on how to keep weight off successfully. "A low-carb diet may be a little bit more effective than a low-fat diet, but in the long run, both diets are not significantly different from each other in terms of weight loss," Hu told Live Science.

Because many diets produce similar results for weight loss, it's time to go beyond looking at macronutrients for weight loss, Hu said. Now, the focus should be on the quality of the foods that are eaten, he said. The majority of studies focus on macronutrient composition without paying attention to the quality of foods, he said.

And quality counts — people who eat a lot of refined starches and added sugars are more likely to feel hungry and regain their weight because these foods aren't satiating, Hu said. "On the other hand, if you eat a healthy diet with high-quality foods like fruits and vegetables, high-fiber whole grains and [healthy fats such as] avocados and nuts," you may be able to lose more weight and also sustain your weight loss with that kind of diet, he said. [Best Diet and Nutrition Apps]

Of course, if you really want to lose a lot of weight in a short amount of time, you can cut one-third or one-half of your total calories. But although that can be a very quick fix, the problem is that a quick fix usually doesn't last very long, Hu said.

For longer-term weight loss, people need to think about their overall diet patterns and gradually adapt to these patterns so they can stick with them, he said.

This article is part of a Live Science Special Report on the Science of Weight Loss. It will be updated whenever significant new research warrants. Note that any significant change in diet should be undertaken only after consultation with a physician.

Follow Sara G. Miller on Twitter @SaraGMiller. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.