Smuggled Ancient Wall Carving Returned to Egypt

A 2-foot-long wall carving featuring the pharaoh Seti I is back in Egypt after being repatriated from the United Kingdom, the Egyptian minister of antiquities announced Monday (Dec. 14).

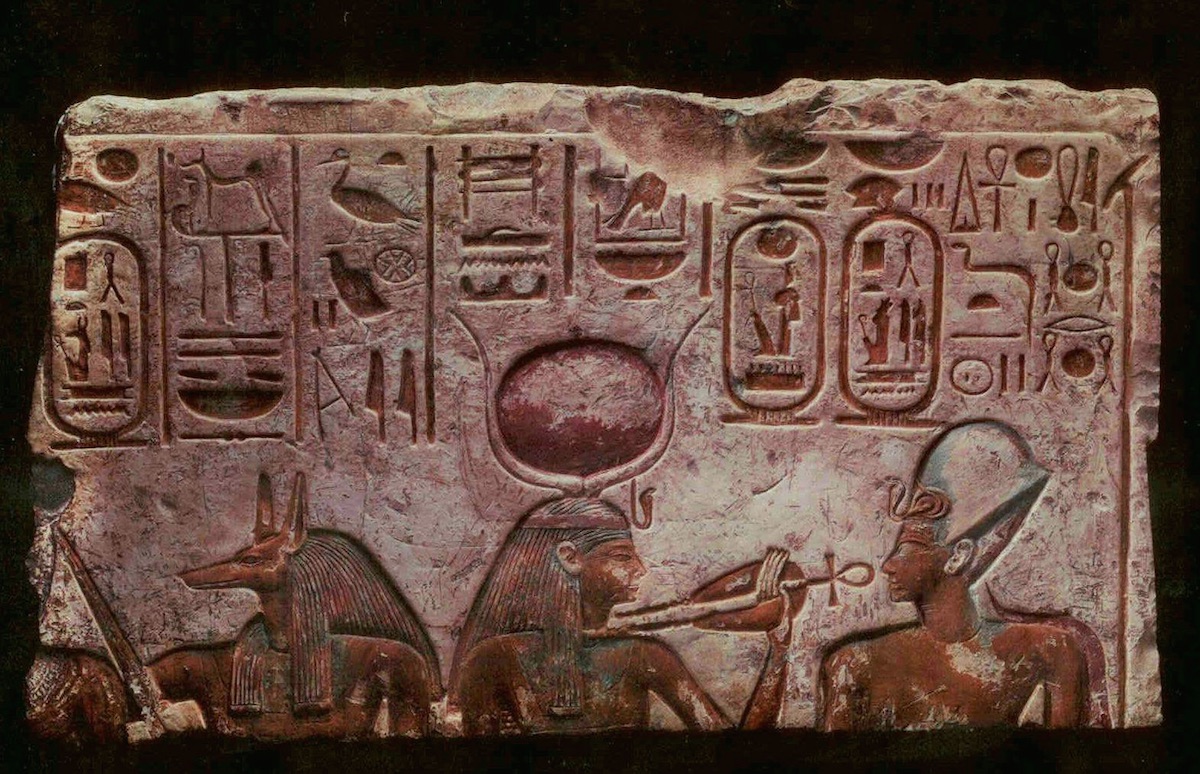

Egypt has long pushed for the return of ancient artifacts — an effort that is only intensifying as political upheaval deters Egyptian tourism. The carving, or stela, is made of pinkish limestone and depicts two ancient Egyptian deities, Hathor and Wepwawet, next to King Seti I, who ruled between about 1290 B.C. and 1279 B.C. According to the Ministry of Antiquities, the piece may have come from a temple, which is notable because no official excavation has uncovered a temple of Seti I; the existence of the stela may mean one is waiting to be discovered.

The stela was smuggled out of Egypt from an illegal dig, according to the Ministry of Antiquities. It will go on display along with other repatriated objects in January at the Cairo Museum. [Reclaimed History: 9 Repatriated Egyptian Antiquities]

Illegal antiquities are part of a bustling underground market. In April, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) announced that it had recovered more than 7,000 cultural items from around the world during a five-year investigation dubbed "Operation Mummy's Curse." Among these items was a set of funerary boat figurines from Egypt, which went on display at the Cairo Museum this month. ICE also returned 65 ancient coins, limestone carvings and a painted Greco-Roman style sarcophagus to Egypt in April; more than 80 items have been returned to Egypt since 2007, according to the agency. International smuggling and money-laundering rings sneak objects out of Egypt and other countries and sell them on the private market.

In November, for example, an Austrian was caught trying to sell an ushabti, a small statue placed in tombs in ancient Egypt to do the dead's work in the afterlife. The ushabti, which dated back to the 26th Dynasty (664 B.C. to 525 B.C.), was excavated illegally and was smuggled out of Egypt, according to the country's Ministry of Antiquities. The Ministry successfully lobbied to get the statue back. Other returned objects, like a Greco-Roman funeral mask delivered to the cultural bureau in Berlin, are passed down from earlier eras when antiques flowed freely out of Egypt. In November, the Ministry of Antiquities reported the return of that mask to Cairo.

The effort to bring smuggled antiques home is long-running, and sometimes veers into controversial territory. Zahi Hawass, who headed Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities from 2002 until 2011 (when the upheaval in the country's government ultimately ousted him from his post and reorganized the agency), has argued for the return of artifacts removed from Egypt during the region's colonial past. In 2010, he released a "wish list" that included the Rosetta Stone, currently among the most-visited objects at the British Museum in London. That stela — whose inscriptions are in hieroglyphs, Demotic script and ancient Greek — was discovered by a French soldier in 1799 during Napoleon Bonaparte's incursion and then was claimed by the British when they defeated the French forces in Egypt and Syria.

The legalities surrounding artifacts removed from Egypt a century or two ago are often murky, and museums frequently resist repatriation. In some cases, though, items are returned voluntarily. In 2010, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York returned 19 small items from its Egyptian collection. All of the items originated in the famous tomb of Tutankhamun. Most were simple fragments or scraps, but four were small objects found in the possessions of archaeologist and tomb excavator Howard Carter after his death, including a tiny bronze dog.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.