Why Humans Have Slender Faces and Neanderthals Don't

Neanderthals had protruding facial features because of the way their bodies deposited and dealt with bone, a new study finds.

In Neanderthals, facial bone deposits continue into the teenage years, whereas in humans (Homo sapiens), bone removal during childhood leads to a flatter face, the researchers found.

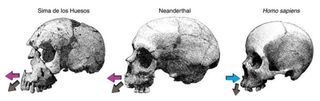

Neanderthals, the closest extinct relatives of humans, lived in Eurasia from about 200,000 to 30,000 years ago. However, their protruding jaws, noses and brows raise questions about how and when humans and Neanderthals separated. [In Photos: Neanderthal Burials Uncovered]

"This is an important piece of the puzzle of evolution," study lead author Rodrigo Lacruz, an assistant professor at New York University’s College of Dentistry (NYUCD), said in a statement.

Some scientists think that Neanderthals and humans are on the same branch of the family tree. "However, our findings, based upon facial growth patterns, indicate they are indeed sufficiently distinct from one another," Lacruz said.

To investigate this question, the researchers examined the facial bones of Neanderthals. Bone is created with bone-forming cells called osteoblasts, and it's broken down with bone-absorbing cells called osteoclasts. Bone in human faces has bone-absorbing cells on its outermost layers. In contrast, Neanderthals had extensive bone buildup in this area, the researchers found.

The researchers were equipped with an electron microscope and portable confocal microscope (a microscope that can help make detailed 3D images) developed by study co-author Timothy Bromage of NYUCD's Department of Biomaterials. The scientists mapped bone-cell deposits and bone resorption, the process in which osteoclasts break down bone, on the outer layer of young Neanderthals' facial skeletons.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists studied several skulls of Neanderthal children from two locations: the British territory of Gibraltar and the La Quina site in southwestern France. The scientists also looked at four teenage hominin faces from the Sima de los Huesos site in north-central Spain, all dating to about 400,000 years ago. The Sima fossils are likely Neanderthal ancestors, given that they have similar anatomical and genomic features, the researchers said.

"Cellular processes relating to growth are preserved on the bones," Bromage said. "Resorption can be seen as craterlike structures, called lacunae, on the bone surface, whereas layers of osteoblast deposits have a relatively smooth appearance."

An analysis showed that both humans and their ancient cousins demonstrate a gradual increase in bone deposits after birth. But while humans resorb some of that bone, especially in the lower face, in childhood, Neanderthals and the Sima individuals continued to build bone deposits throughout their teenage years, leading to protruding jaws.

"This difference in growth at least partially explains the reduction in our faces that occurred in the last 200,000 years," study co-author Paul O’Higgins, a foundation professor of anatomy at Hull York Medical School in the United Kingdom, said in a statement.

The finding shows that Neanderthals and the Sima fossils share a similar facial growth pattern, Lacruz said.

"It's actually humans who are developmentally derived, meaning that humans deviated from the ancestral pattern," Lacruz said. "In that sense, the face that is unique is the modern human face, and the next phase of research is to identify how and when modern humans acquired their facial-growth development plan."

These evolutionary differences may also explain the variation in facial size and shape among modern humans, Lacruz added.

The study was published online Dec. 7 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular