Historic Photos Paint Picture of Greenland Ice Loss

SAN FRANCISCO — A picture is worth a thousand words, or, in the case of the Greenland Ice Sheet, maybe a thousand scientific measurements.

A group of scientists has used a trove of historic aerial photos of the periphery of the ice sheet to estimate how much ice it lost over the course of the 20th century, before detailed satellite observations became available. From that number, they have calculated Greenland’s contribution to sea level rise over that time, which they estimate to be about 10 to 17 percent of the total global sea level rise of about 1 foot since 1900.

This picture of the ice sheet’s past behavior, presented here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union and detailed in the Dec. 16 issue of the journal Nature, could help give researchers a better handle on how it might react to further future warming, improving models of ice melt and sea level rise.

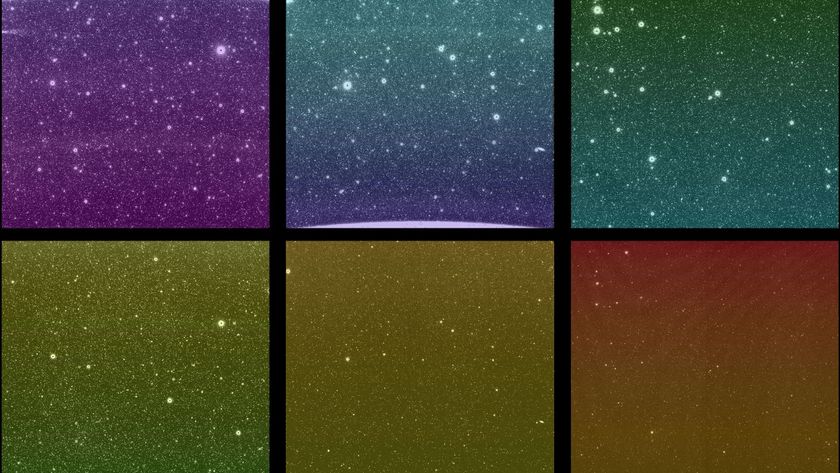

To monitor the Earth’s vast, remote expanses of polar ice, scientists rely on observations taken by orbiting satellites. But good satellite measurements have only been around since the 1980s, and “before that, there’s not much information,” study co-author Kurt Kjær, of the University of Copenhagen, said.

That’s where a huge Danish archive of some 160,000 historical photos of Greenland, spanning a period from the 1930s through the late 1980s, comes in.

For this study, the researchers used photos from a systematic aerial survey of Greenland’s glaciers conducted from 1978 to 1987. They compared the elevation of the glaciers in the ‘80s to the bathtub watermark-like signatures that showed the maximum elevation those glaciers had reached at the end of the Little Ice Age around the turn of the 20th century. Those elevations effectively helped them morph two-dimensional photos into a three-dimensional picture of the ice sheet at different points in time.

Once Stable Greenland Glacier Facing Rapid Melt Climate Change Brings New Risks to Greenland Newfangled ‘Icepod’ Tracks Greenland’s Melting Ice Sheets

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

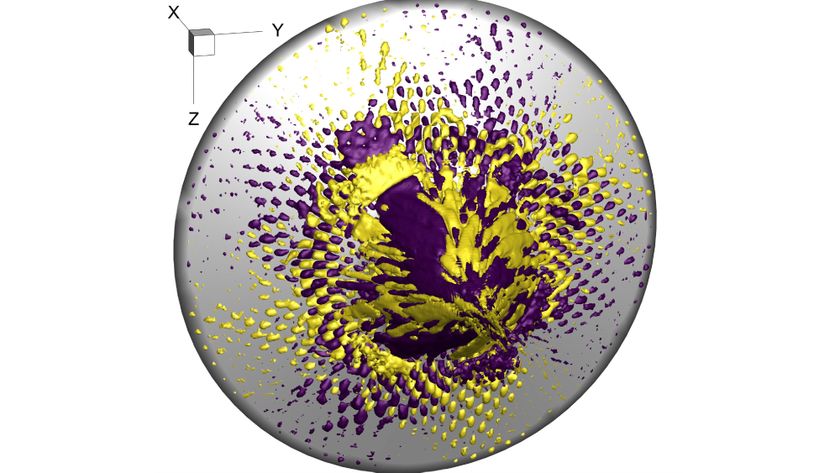

They could then plug that information into models to see how much ice Greenland lost over the 20th century, as well as how that loss varied over time and at different points around the ice sheet.

While the ice sheet overall lost mass during the century, there were periods of more rapid loss and ones where the ice sheet appeared to be roughly stable.

Certain areas of the ice sheet also accounted for the bulk of the ice loss, namely the northwestern and southeastern parts of the ice sheet — the same pattern largely seen today, although some northeastern glaciers that were thought to be stable have recently shown signs of substantial melt and retreat.

The team also compared the ice loss up until the mid-1980s to that observed by satellites over roughly the last decade and found that today the rate of ice loss is twice the 20th century average, mostly because of increased water runoff from the ice sheet’s surface.

The estimates of ice loss also helped them calculate the amount of sea level rise contributed by the ice sheet prior to 1990 — a number missing from the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report because of the lack of direct observations. They calculated that the ice sheet contributed at least an inch of sea level rise during the 20th century, or somewhere between 10 and 17 percent of the total.

The information from the study helps improve scientists’ understanding of the behavior of the ice sheet and what processes control the loss of ice, Beata Csatho, a geophysicist at the University of Buffalo in New York who was not involved with the work, said in a commentary published in the same issue of Nature. A better understanding of these processes could in turn lead to more accurate projections of how Greenland might continue to change in the future, as well as how much sea level rise it might contribute.

It’s possible that even older photographs in the Danish archive could be used in a similar way to provide even more pre-satellite observations of changes to Greenland’s ice, as well as more in-depths studies of particular glaciers

“There’s so many things that we can do with the archives to further broaden our knowledge of the glaciers,” co-author Anders Bjørk, also of the University of Copenhagen, said.

You May Also Like: Arctic Gets Check-Up: Temperature Highest on Record El Niño Impacts Could Spark Amazon Fires Next Fall Heat, Humidity Combine to Threaten Millions in Future

Originally published on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.