The Art of Science: Why Researchers Should Think Like Designers (Op-Ed)

Ayse Birsel, is an award-winning designer and co-founder of Birsel + Seck. Her work has appeared in museums including the MoMA, the Cooper Hewitt and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She is the author of "Design the Life You Love: A Step-by-Step Guide to Building a Meaningful Future" (Ten Speed Press, 2015). Ten Speed Press is an imprint of Penguin Random House. More on Ayse Birsel at www.aysebirsel.com and on Twitter, @aysebirselseck. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

This fall I read "The Martian" (Crown, 2014) by Andy Weir, and it made me want to be a scientist. I was drawn to Mark Watney, the main character, by his optimism, creativity and problem solving — which he maintained even in the face of the most dire conditions (it doesn't get any more dire than being left alone on Mars!).

It's because I share those three traits — optimism, creativity and problem solving — that I'm a product designer. But while science is about explaining the world and universe based on facts, my field is about imagining the world based on possibilities. Designers look at everyday products, services and experiences in new ways, and design to improve life. In doing so, we tag-team with engineers, who are indispensable to making our designs manufacturable and real.

Design for life

In my career, I've designed hundreds of products, from toilet seats to office systems to kitchen gadgets to pens. Some of my designs you might have already used, such as a potato peeler for Giada's collection at Target to the Herman Miller Resolve Office System you may be sitting in as you read this article.

Even though the products vary greatly, the red thread across all of them is my design process — Deconstruction:Reconstruction. It helps me, and those around me, think differently and bring new solutions to old problems. Even problems in life.

"Design the Life You Love" started as an experiment. I think that people's lives are their biggest design projects — full of constraints, challenges, and opposing needs and wants — and I wanted to see if I could apply my process and tools to living. You simply cannot have everything. If you want to have more, you need to make what you want and what you need co-exist. This requires that you think like a designer.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

I fell in love with the human scale of design when I was 16. A family friend came to tea and asked me if I knew what product design was. I didn't. Using a teacup, he explained to me that the edge of the cup is curved to better fit people's lips, the handle is to help people hold hot liquid in their hands and the saucer is there so that if I spilled some of my tea, I wouldn't ruin my mom's tablecloth.

Design 101 for scientists

Since I often work closely with engineers, I've come to realize that the design process has uncanny similarity to the scientific and engineering processes, yet it differs in key ways. By understanding the design process I use, everyone, including scientists, can gain insight into solving complex problems that they might want to think differently about … including how to live a complete life.

Here are a few simple steps to help you tackle challenges like a designer:

00. Warm up:

Draw something to warm up your right brain (if you wonder about the difference between the right and left brains, here is a great article). You might say as a scientist that you don't draw. Come on! Everyone draws. It doesn't have to be masterpiece. Just rest your eyes on something — a flower, a mug, a cat or a person (you can use the template below if you're drawing a person) and draw for 3 minutes. There, now you just sent a signal to your brain that you're going to think creatively. [The Roots of Creativity Found in the Brain ]

01. Deconstruction:

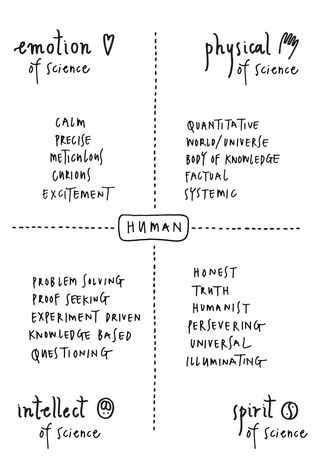

Deconstruction is breaking the whole apart to see what it's made of. You can even deconstruct something very familiar, like science, to see what goes into it. Here is my deconstruction of science across the four quadrants of emotion, physical reality, intellect and spirit (the four quadrants tool is one I use to think holistically).

02. Point of View:

People can shift their points of view intentionally. As this beloved Shakespeare quote says, "There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so." In design, you want to shift from what you know to what you can imagine. I have gathered a couple of tools over time to help shift my perspective from what I know to what I can imagine. My favorite is the metaphor. You can use metaphors to help think about difficult subjects through the lens of something you know. One of my favorite STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art and math) projects is STEAM Carnival by Two Bit Circus, which uses the metaphor of a traveling, high-tech carnival to teach people, young and old, about science. Imagine being inside the Dunk Tank Flambé, which spouts out flames instead of water when a player hits the target with a softball, engulfing in this case my friend John Zapolski in fire. Luckily for John, he is wearing a super-flame-retardant suit. Image is courtesy of photodepot.com and Two Bit Circus.

03. Reconstruction:

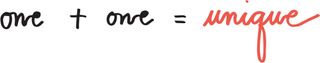

Reconstruction is the other side of Deconstruction. It is about putting the subject back together again, knowing that you cannot have everything. Design is about making choices, and the three circles above symbolize your constraints. What are the three essential components of your new idea, the ones to which you will devote your time and energy? And what new value do they create together?

04. Expression:

Expression is giving your idea form. You build on the foundation of your new idea, and you express it as a unique prototype, a product, a strategy, a mathematical formula or a hypothesis.

This approach is about making design process and tools accessible, especially to nondesigners, around a project everyone shares: In life, people can solve problems with creativity and optimism. [Ditching Gadgets May Boost Creativity ]

Which brings us back to Mars. Even if I cannot go to Mars tomorrow, I would love to work with amazingly creative scientists and engineers to bring design and science together to generate solutions for old (and new) problems. I really want to learn how to think more like a scientist. That would be the best of STEAM: I bring the "A" of Arts and Design, and you bring STEM, and together we do our best left- and right-brain thinking. That would be a dream come true, a life well-designed — perhaps on Mars?

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science .