Photos: 'Lost' Astronomy Plates Show Historic Eclipse and More

When retired astronomer Holger Pedersen visited a basement kitchen in the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen to brew a pot of tea, he discovered an unanticipated treasure trove — hundreds of photographic glass plates imprinted with astronomy observations, offering a unique view of the sky from decades long past. The oldest plates dated back to 1895, when the Institute's Østervold telescope was first installed.

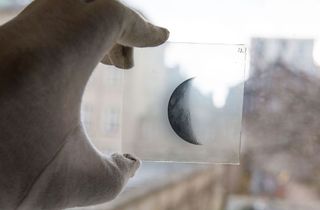

Among the approximately 300 plates is an image of the 1919 solar eclipse, which was the first known evidence to support Einstein's 1915 general theory of relativity. The eclipse photo, which shows light visibly bending around the sun, proved Einstein's prediction that the gravity of massive objects in space would affect light's path. (Image credit: Niels Bohr Institute) [Read the full story on the 'lost' astronomy plates.]

Astronomy from a different age

Many of the glass plates found in the basement storage area were over 100 years old. Different phases of the moon were captured in a series of images taken between 1909 and 1922.

New in box

The boxes found in the Institute's basement kitchen held a number of cartons. One, which had apparently never been opened, held a stack of brass frames that were used to hold the glass tiles in place on the telescope while the images were exposed.

Eye on the sky

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Installed in 1895, the telescope at the University of Copenhagen Observatory on Østervold held two lenses — one for observations, and one for capturing photographic images on 6-inch (16-cm) glass plates. The telescope was one of several astronomical instruments at the Observatory, which remained active until 1996.

The image that proved Einstein was right

A mobile-phone photograph of a copy-plate showing the May 29, 1919 solar eclipse observed at Sobral, Brazil. Ink circles on the plate mark the positions of stars in the open cluster Hyades, Pedersen told Live Science, adding that the circles may have been drawn by astronomers who observed and reported the eclipse.

An 'astronomy archaeologist'

Holger Pedersen, who discovered the 'lost' boxes of photo plates, is retired but keeps an office at the Niels Bohr Institute. He studies and writes about large stony-iron meteorites like the 1,500 lb (700 kilogram) Krasnojarsk meteorite, found in Russia in 1749.

Lunar eclipse

An almost-complete lunar eclipse, taken on February 28, 1896, one in a series of three photographs of the eclipse.

Historic eclipse

Pedersen and colleagues review the copy-plate of the 1919 eclipse, which was likely sent to an astronomer in Copenhagen by British astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington, to confirm his observation's proof of Einstein's theory of general relativity. Archivists in the U.K. were unaware of the plate's existence and "have expressed delight with the discovery," Pedersen said.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.