Ancient Mom: Oldest Brood of Preserved Embryos Found

A tiny, shrimplike creature that lived 508 million years ago has been discovered carrying about two-dozen fossilized eggs with preserved embryos in its body, making it the earliest example of brood care with preserved embryos on record, a new study finds.

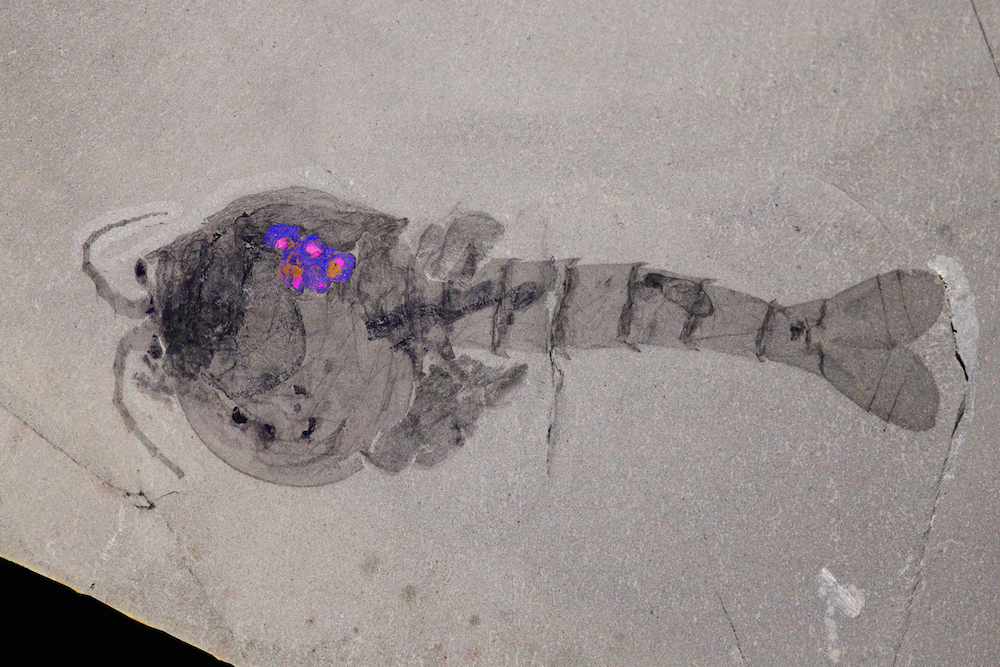

Researchers found the specimen in 1912 in the Burgess Shale of the Canadian Rockies, a site famous for its Cambrian period fossils. In fact, the scientists found numerous fossils — each measuring about 3 inches (7.5 centimeters) long — belonging to the creature called Waptia fieldensis.

Recently, paleontologists revisited the W. fieldensis fossils, looking at 979 specimens from the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada and 866 specimens housed at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. After an extensive search, the researchers found that five of the little creatures from the Canadian collection contained eggs. [See Images of the Egg-Carrying Animal and Other Cambrian Creatures]

Carrying eggs is an example of brood care. For instance, kangaroos practice brood care by carrying their young in pouches, "which, like other parental traits, enhances offspring fitness," the researchers wrote in the study.

"As the oldest direct evidence of a creature caring for its offspring, the discovery adds another piece to our understanding of brood-care practices during the Cambrian explosion, a period of rapid evolutionary development when most major animal groups appear in the fossil record," Jean-Bernard Caron, a curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum and an associate professor in the departments of Earth Sciences and Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto, said in a statement.

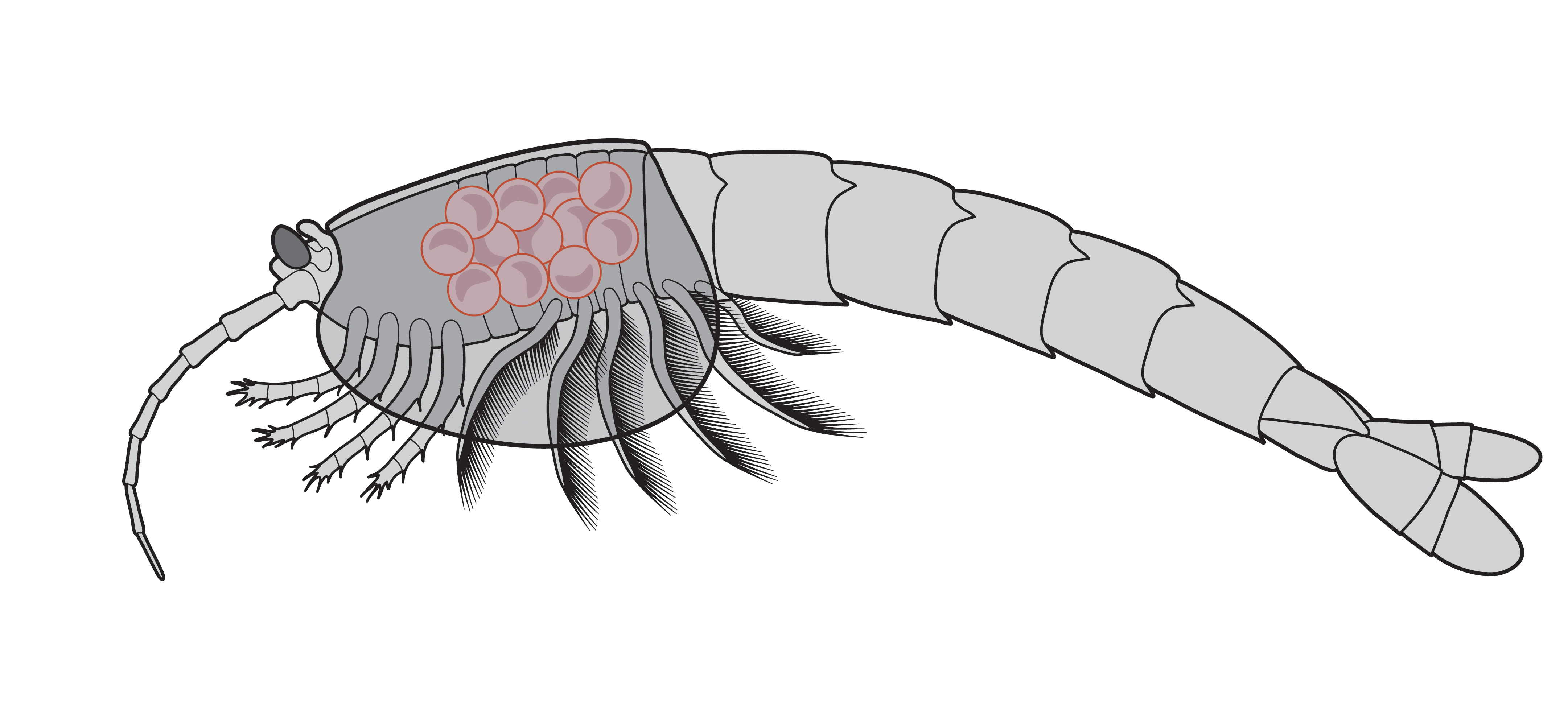

W. fieldensis is an ancestor of modern arthropods, a group that includes invertebrates such as crayfish, butterflies and scorpions. A detailed microscopic analysis revealed the critter's intriguing body shape. It has a two-part structure called a bivalve carapace covering the front segment of its body near the head.

The researchers noticed clusters of egg-shaped objects on the underside of the carapace. This suggests the structure helped the animal hold eggs, enabling the creature to care for its brood, Caron said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Furthermore, the egg-shaped clusters are arranged in a single layer on each side of the body, with barely any overlap among the 0.07-inch-long (2 millimeters) eggs, the researchers said. Some of the creatures hold eggs that are equidistant from one another, while others have eggs that are spaced closely together. These differences are likely due to the angle at which the organisms were buried and whether they were moved during that time.

"This creature is expanding our perspective on the diversification of brood care in early arthropods," said study co-author Jean Vannier, a senior researcher of geology at the French National Center for Scientific Research.

Vannier compared W. fieldensis to another ancient arthropod, Kunmingella douvillei, a 515-million-year-old specimen discovered in China. K. douvillei was also found with eggs inside its body, but those eggs didn't contain embryos and were found lower in its body, attached to its appendages.

"The relatively large size of the eggs and the small number of them [in W. fieldensis] contrasts with the high number of small eggs found previously in another bivalved arthropod, known as Kunmingella douvillei," Vannier said. "And though that creature predates Waptia by about 7 million years, none of its eggs contained embryos." [See Images of Ancient 4-Eyed Arthropod with Toothy Claws]

That W. fieldensis and K. douvillei carried their eggs in different ways hints that brood care evolved in a number of ways during the Cambrian period. Moreover, the bivalved carapace likely played an important role in arthropods' brood care, as researchers have already noted the structure's presence in egg-carrying ostracods (sometimes called seed shrimp) dating to 450 million years ago, the researchers said.

The study was published online Dec. 17 in the journal Current Biology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.