Ingredients of Plague Risk in Western US Identified

Small outbreaks of the plague still occur in the western United States, and now new research shows these clusters don't happen at random. Instead, they tend to pop up in areas that have certain mix of climates, animals and elevation, a new study finds.

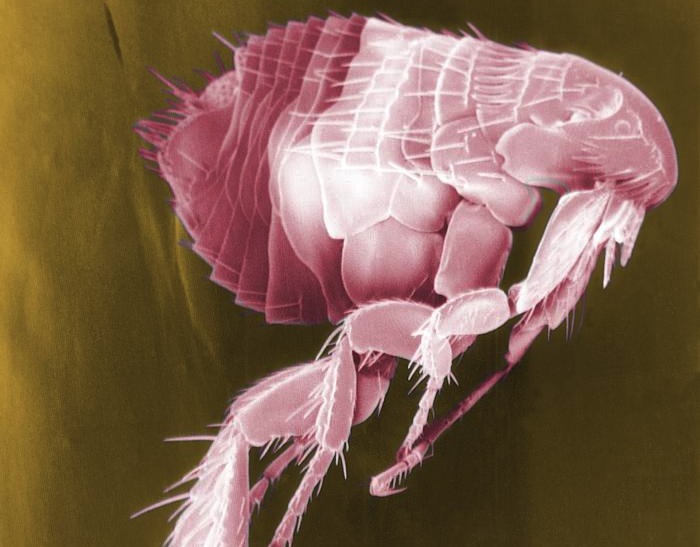

Every year, an average of seven people in the western United States are infected with the bacteria that cause plague (Yersinia pestis). The bacteria — infamous for killing millions of people in Europe during the Middle Ages — typically live in rodents and fleas.

In the new study, researchers wanted "to identify and map those areas with the greatest potential for human exposure to this infection," Michael Walsh, an assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics in the School of Public Health at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center in New York, said in a statement. The researchers used surveillance data of plague in wild and domestic animals from all over the American West. [Pictures of a Killer: A Plague Gallery]

The researchers determined that plague cases in the United States tend to happen in areas that have large populations of deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), rainy weather, moderate elevations and ground largely covered with man-made surfaces, such as roads and buildings.

Plague first came to the United States in 1900, when steamships carrying infected rats docked at U.S. port cities, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The bacteria then spread from urban rats to rural rodents, eventually becoming endemic (or constantly present) in animals in the rural American West.

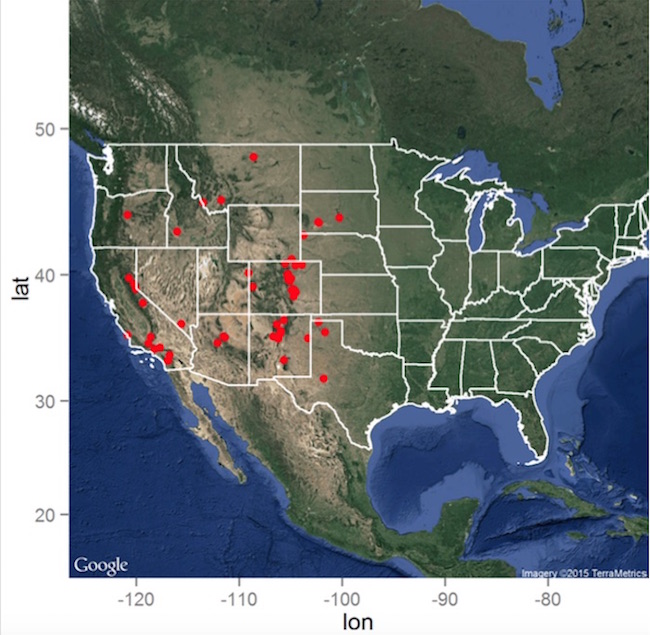

These days, most human cases of plague in the United States happen in two regions: one area stretches across southern Colorado and the northern parts of New Mexico and Arizona, while the other region includes California, southern Oregon and western Nevada, the researchers said.

But little is known about what specific factors — such as climate, land type and elevation — lead to small clusters of plague cases within these broad areas. To investigate, the researchers mapped 66 confirmed cases of plague in wild animals and pets that officials had documented between 2000 and 2015. Then, the researchers zeroed in on several conditions to determine what had contributed to outbreaks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Plague risk factors

The resulting models showed that the presence of deer mice was the most influential factor contributing to plague cases, followed by elevation, the distance between the place where an infected animal was found and a man-made surface, and the average rainfall during the area's wettest and driest seasons.

Areas at higher elevations were associated with increased risk of plague in animals, but only among elevations lower than 1.2 miles (2 kilometers), the researchers found.

"The reason for such a threshold is not entirely clear," but might have to do with habitat availability, the researchers wrote in the study. For instance, deer mice prefer living around pinyon and juniper pines, trees that grow at moderate but not high elevations, the researchers said.

Moreover, rainfall influenced plague risk. Places that had wet weather during the rainy season had a higher plague risk, but only up to 4 inches (100 millimeters) of rain in a three-month period. Beyond that threshold, plague risk declined, the researchers found.

Likewise, increased rainfall during the dry season also corresponded to increased plague risk, but only up to a threshold of 2 inches (50 mm) of rain, after which plague risk dropped to zero. It's likely that some (but not too much) rain leads to better food availability for rodents, the researchers said, which would explain this threshold. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

Finally, areas of animal habitat that were close to man-made surfaces also had an increased plague risk.

"To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an influence of developed land on animal plague occurrence in the U.S.," the researchers said. It's likely that developed areas bring wild animals closer together to people and domestic animals, increasing the risk of spreading plague, the researchers said.

The findings may help public health officials monitor areas in the American West that are at high risk of plague infection, Walsh said.

The study was published online Dec. 14 in the journal PeerJ.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.