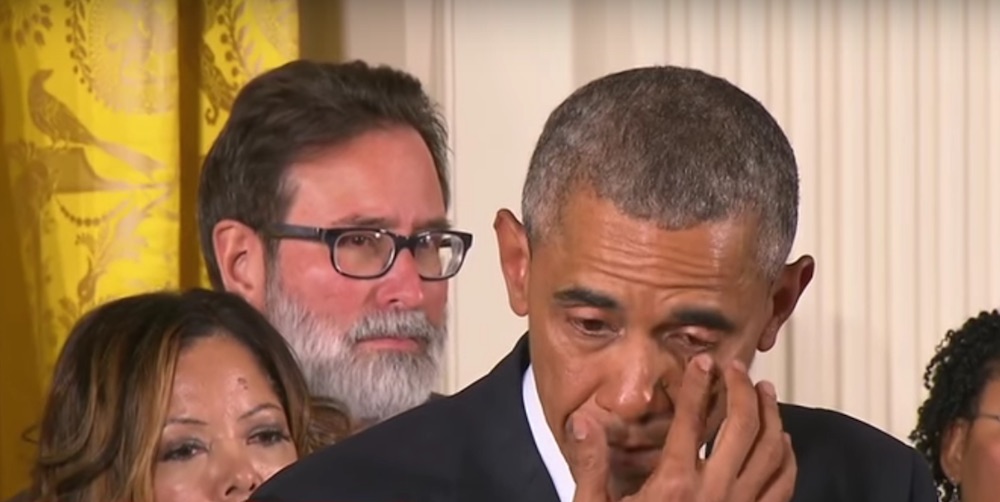

In his call on Tuesday for stricter gun-control measures, President Barack Obama wiped away tears as he mentioned the December 2012 massacre of innocent children at Sandy Hook Elementary School.

"First graders, in Newtown. First graders," Obama said, referencing the youngest victims of the Newtown, Connecticut, shooting. "Every time I think about those kids, it gets me mad. And by the way, it happens on the streets of Chicago every day."

Many news stories on the president's speech noted his tears prominently — in the headline or the first few lines of the article — highlighting that it's still unusual to see a man crying publicly. But just what is the science behind male tears?

It turns out that although men do cry, they may be biologically predisposed to cry less than women. Still, while male tears are less common and less intense, men weep at the same types of emotional triggers as women do, research suggests.

What's more, Obama's ability to shed a few tears may even make viewers feel emotionally close to him, other research suggests. [15 Weird Things Humans Do Every Day, and Why]

Men's tears versus women's tears

It's a well-worn stereotype: Women well up at sad news, weepy movies and even the odd diaper commercial, whereas men remain dry-eyed in the most harrowing and heartbreaking situations.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But it turns out that the stereotype may actually have some grounding in fact. Women cry dozens of times a year, on average — up to five times more often than men do, on average, according to research reported by psychologists Ivan Nyklicek, Lydia Temoshok and Ad Vingerhoets, all of Tilburg University in the Netherlands, in their book "Emotional Expression and Health" (Routledge, 2004).

Men's crying jags are also briefer, lasting just 2 to 3 minutes on average, compared with 6 minutes for women, the book says. (Women are also likelier to have marathon sob fests that last longer than an hour, according to Vingerhoets' research.)

The weepier nature of women shows up in cultures around the world. However, in some poorer countries — such as Ghana, Nepal and Nigeria — people cry less overall, and men cry only slightly less than women, according to a 2011 study in the journal Cross-Cultural Research. That could be because poorer cultures dissuade emotional expression, while people in richer countries such as the United States sob more because the culture encourages it, the researchers hypothesized.

Biological difference?

The river of tears dividing men and women may have a biological basis. Women's higher levels of the hormone prolactin (which is involved in breast-feeding) may spur them to tears, whereas men's higher testosterone levels may inhibit tears, one theory holds. In fact, one 1998 study in the journal Cornea found that premenopausal women with lower levels of prolactin and higher testosterone levels shed fewer tears than women with high prolactin and low testosterone.

And until puberty, with its hormonal onslaught that affects boys and girls very differently, both sexes cry about equally, according to a 2002 study in the British Journal of Developmental Psychology.

Men's more stoic demeanor may be about simple geometry. Women have shallower, shorter tear ducts that are more easily overtopped, leading to more visible tears, according to a paper published in the 1960s in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

Some researchers have argued that the gender difference in tears is at least partly cultural. Stories from long-ago cultures — including those in the Bible, "The Iliad" and the medieval knights' tales — are replete with sobbing, powerful, manly men.

The discrepancy in male tears versus female tears may be a more recent phenomenon that began when men went to work in factories, according to the book "Crying: A Natural and Cultural History of Tears" (W. W. Norton & Co., 2001). Hard-charging bosses may have dissuaded emotional displays in order to increase productivity, and although some women went to work too, they were more likely than men to stay in the home, where tears were not so openly discouraged.

Men who exhibit more "androgynous" traits, or those stereotypically defined as feminine, tend to cry more frequently than those with more stereotypically masculine traits, according to a 2004 study conducted by Kleenex. (The researchers don't report how "androgyny" was defined, nor was it clear that the study was peer reviewed, the standard process by which scientific research is vetted.)

However, the triggers of tears in men were similar to those in women in the study: The death of a loved one had caused 74 percent of the surveyed men to cry, while tearjerker movies, breakups and even happy moments in films or movies spurred waterworks among the men in the Kleenex study, according to the findings.

Tears spur closeness and emotions

But regardless of whether men cry more than women, Obama's tears may have made people feel closer to him, according to a theory that holds that people cry to signal vulnerability. Tears blur a person's vision, making them less powerful as aggressors, the theory goes.

That, in turn, could form a powerful signal to a potential competitor that you are not a threat, potentially eliciting mercy and sympathy, Live Science previously reported. If two people both reveal that their defenses are lowered, that may spur bonding, the theory says.

Other theories suggest that crying may help people get in touch with their own emotions, meaning a lack of tears can hint that a person has trouble accessing their feelings. About 22 percent of people with Sjogren's syndrome, who have trouble producing tears, also have difficulty identifying the emotions they're feeling, according to a 2012 study in the journal Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.