Photos: Sharks with Nose Plugs Have Trouble Getting Home

Leopard sharks may use smell to help them navigate the ocean, a new study finds. Researchers captured 26 sharks near the beaches of La Jolla in southern California and fitted them with acoustic trackers. Then, they released the sharks about 6 miles (9 kilometers) from shore, but plugged 11 of the sharks' noses with cotton balls soaked in Vaseline. Surprisingly, the sharks with impaired smell had more trouble returning to shore than the sharks without stuffed noses did, the researchers found. [Read the Full Story on the Leopard Sharks]

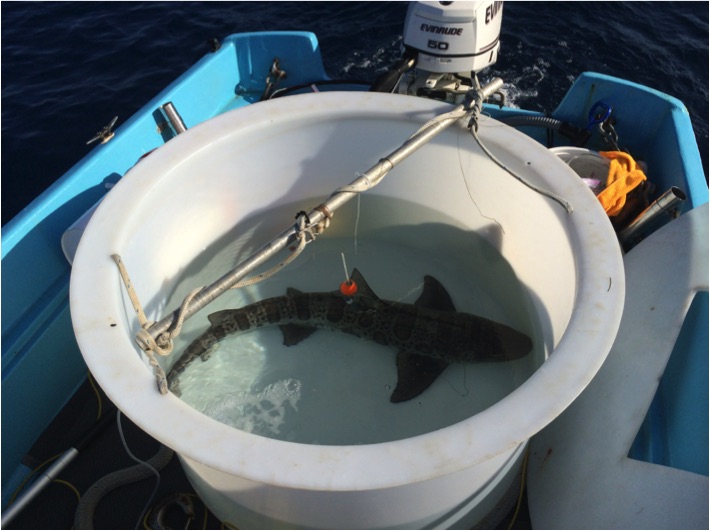

Shark in a tub

The researchers captured the female leopard sharks along the La Jolla coast, and then placed them in water tubs aboard their research boat, a 17-foot-long (5 meters) Boston whaler. (Photo credit: Jamie Canepa)

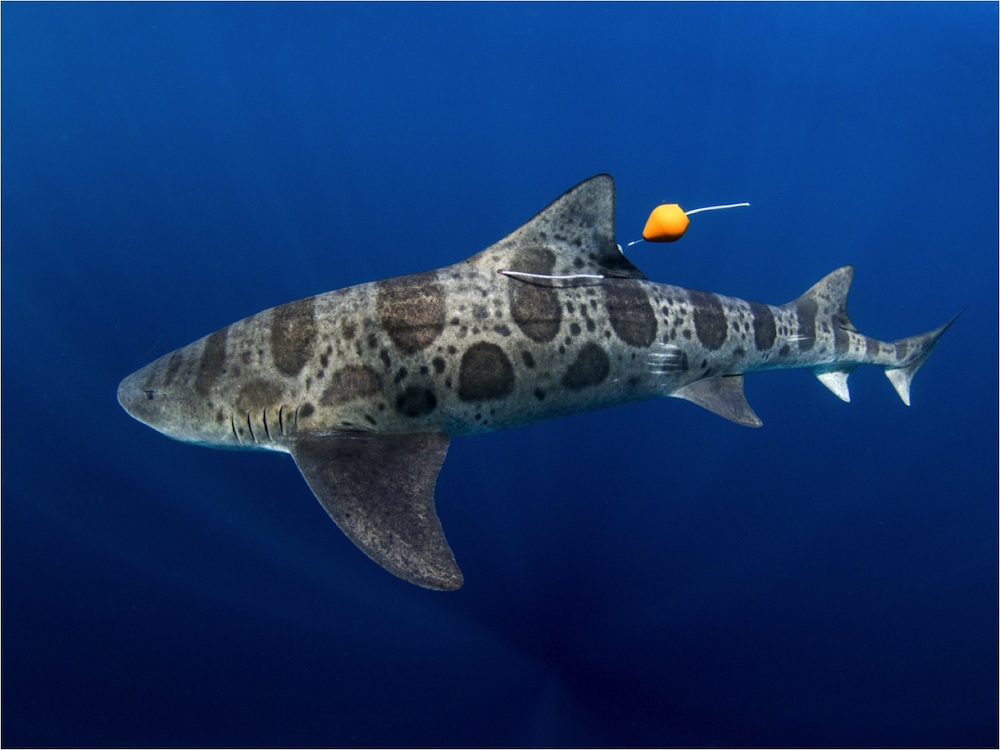

Tagged shark

After placing an acoustic tracker on each of the 26 leopard sharks, the researchers dropped the sharks off at a location 6 miles from shore. (Photo credit: Kyle McBurnie)

Acoustic tag

The acoustic tag stayed attached to each shark for about 4 hours. After that, it would fall off, and the researchers would retrieve it to collect the GPS data and then put it on the next shark. (Photo credit: Andrew Nosal)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Underwater view

Leopard sharks are about 5 feet (1.5 m) long. (Photo credit: Kyle McBurnie)

Spotted shark

Study lead researcher Andrew Nosal, a postdoctoral researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the Birch Aquarium, holds a leopard shark. Most of the sharks without plugged noses oriented themselves within about 30 minutes, and then swam in straight lines back to shore. (Photo credit: Courtesy Andrew Nosal)

Shark shadow

A researcher puts a leopard shark back into the water. On average, the sharks with the unplugged noses made it about 62 percent of the way to shore before their acoustic trackers fell off. (Photo credit: Jamie Canepa)

Shark gymnastics

Researchers flipped the sharks in the boat and placed them belly up, so that the sharks were on their backs, Nosal said. This position calms the animals, and let the researchers insert the Vaseline-coated nose plugs. (Photo credit: Jamie Canepa)

No peeking

Researchers placed the leopard sharks in covered tubs so that the sharks couldn't use the sun to tell where they were going. (Photo credit: Jamie Canepa)

Tag time

A researcher attaches an acoustic tag to the fin of a leopard shark. The sharks that had plugged noses had trouble finding their way back to shore. Many of them wandered in windy paths. On average, the impaired-smell group made it only 37 percent of the way to shore after the 4-hour experiment. (Photo credit: Jamie Canepa)

Wet research

A researcher puts a tagged leopard shark into the water. Although smell is likely important in ocean navigation, sharks probably also use other senses, such as sight or magnetic or electrical senses, to determine where they're going, the researchers suggest. (Photo credit: Jamie Canepa)

Fishy in the sea

The new study raises more questions about what the sharks are smelling, said Jelle Atema, a professor of biology at the Boston University Marine Program who was not involved in the research. It's also possible that sharks don't use smell to navigate, but when their noses were plugged, it changed their behavior, prompting them to swim in windy paths, he said. (Photo credit: Jamie Canepa)

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.