Ancient Rome Was Infested with Human Parasites, Poop Shows

The Roman Empire is famous for its advanced sanitation — public baths and toilets — but human poop from the region shows that it was rife with parasites.

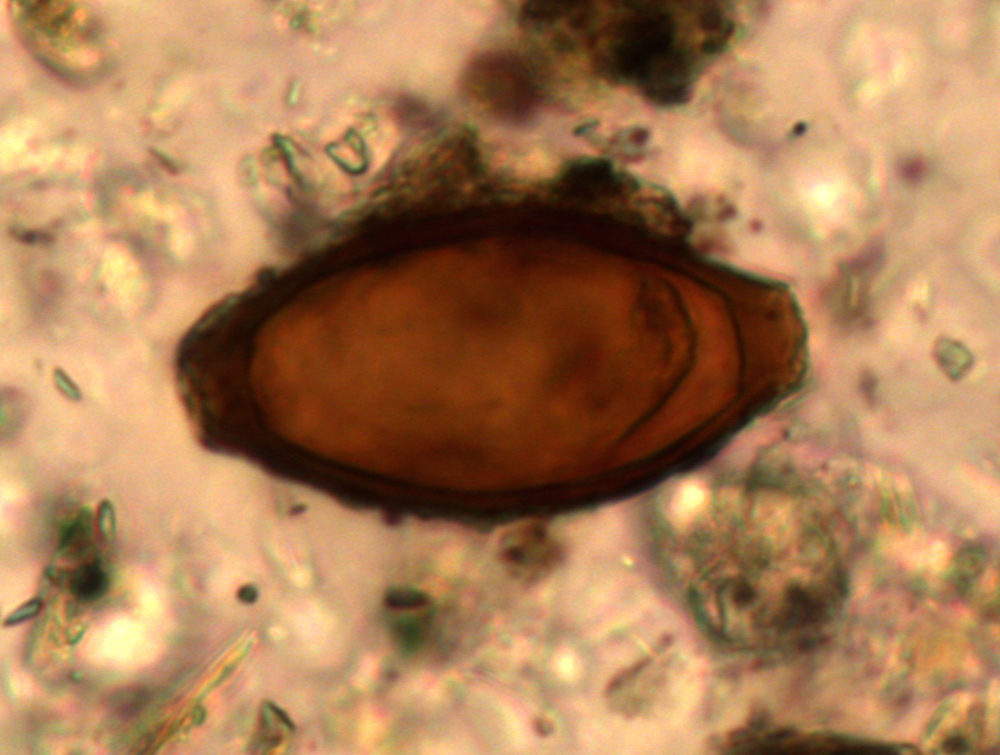

In fact, the empire was infested with a greater number of human parasites, such as whipworm, roundworm and Entamoeba histolytica dysentery, than during prior time periods.

"I was very surprised to find that compared with the Bronze Age and Iron Age, there was no drop in the kind of parasites that are spread by poor sanitation during the Roman period," said the study's author Piers Mitchell, a lecturer of biological anthropology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. [Photos: Parasite Eggs Found Hiding in 500-Year-Old Latrine]

In spite of such admirable baths and toilets, "neither of those things seemed to have actually increased the health of people in Roman times," although it probably would have helped them smell better, Mitchell told Live Science.

Rome introduced sanitation technology about 2,000 years ago, including public bathrooms with multiseat latrines (an idea borrowed from the Greeks), heated public baths, sewage systems and drinking water piped from aqueducts, Mitchell said. Romans also passed legislation whereby human waste from towns and cities would be carted to the countryside, he wrote in the study.

Mitchell wondered whether these inventions improved the health of the empire's inhabitants. He combed through previous research on the empire's intestinal parasites — microscopic remains that researchers have found over the years in latrine soil, coprolites (fossilized excrement) and burial dirt that contains decomposed human remains. He also reviewed studies analyzing Rome's ectoparasites — that is, parasites found on the outside of the body, such as fleas, lice and bedbugs — in textiles and combs.

Surprisingly, ectoparasites were just as common in the Roman Empire, where people regularly bathed, as they were in Viking and medieval populations — groups of people who didn't bathe frequently, Mitchell found.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Parasite paradise

Modern research shows that access to clean drinking water and toilets decreases disease and parasites — so why didn't the Roman Empire see fewer whipworms, roundworms and tapeworms?

Perhaps the warm communal waters of the bathhouses helped spread the parasitic worms, Mitchell said. The water wasn't frequently changed in some baths, and a layer of scum (and parasites) may have covered the water, he said.

Moreover, Roman farmers may have used human excrement that the empire carted to the countryside as fertilizer for their crops.

"Fertilizing crops with feces does increase crop yield, but unfortunately, the Romans wouldn't have realized that it would have resulted in reinfection of the general population" who ate the crops fertilized with parasite-ridden poop, he said.

Also, many Romans enjoyed eating an uncooked and fermented fish sauce called garum. "Roman enthusiasm" for garum may explain why fish tapeworm parasites were so common in the empire, as the parasites live in fish. (Cooking the fish kills the parasite, Mitchell said.)

Today, parasite infections are often treated with antibiotics. But during the Roman period, doctors resorted to balancing the body's "four humors" — black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm.

In fact, the famous medical practitioner Galen (A.D. 130 to A.D. 210) "believed that helminths [parasitic worms] were formed from spontaneous generation in putrefied matter under the effect of heat," Mitchell wrote in the study.

Galen even recommended a treatment consisting of a modified diet, bloodletting and medicines believed to balance the humors, Mitchell said. It also appears that Romans regularly used delousing combs to rid themselves of lice and fleas, Mitchell said.

The study will be published online Friday (Jan. 8) in the journal Parasitology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.