First Flower Seeds from Dinosaur Era Discovered

The world may never know if dinosaurs stopped to smell the flowers, but scientists have uncovered a few more clues about the ancient blossoms that grew alongside ankylosaurs and iguanadons. Recently, researchers discovered tiny Cretaceous flower seeds dating back 110 million to 125 million years, the oldest-known seeds of flowering plants. These puny pips offer a glimpse into the biology powering the ancient predecessors of all modern flowers.

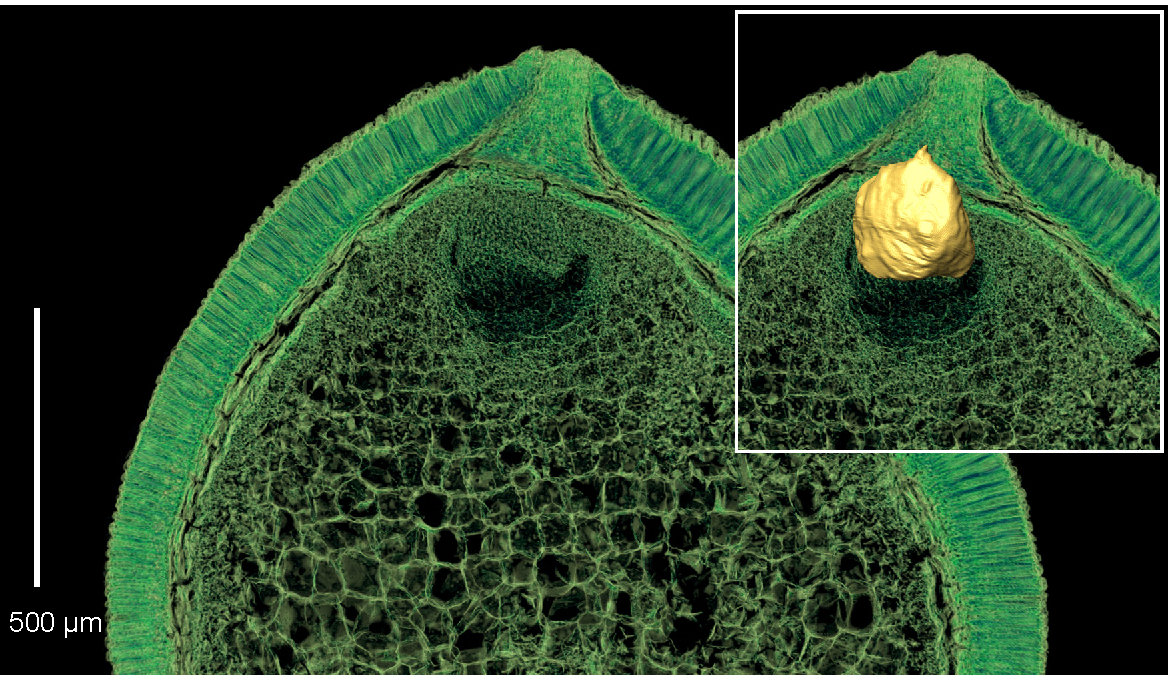

The seeds are miniscule — the largest was no more than 0.1 inch (2.5 millimeters) in diameter — and unusually well-preserved, in such good condition that their internal cell structures were still visible. For the first time, scientists were able to detect seed embryos, the part of the seed where a new plant grows and emerges, and food storage tissues surrounding them. These structures offered a rare glimpse into how the Cretaceous seeds grew, and how they compare with plants alive today.

Else Marie Friis, lead author of the study and professor emerita at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, has analyzed some of these fossil remains of angiosperms — flowering plants — preserved in soils in Portugal and North America. She and her colleagues used a relatively new visualization technique — synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy (SRXTM), which allowed them to explore the delicate fossils without damaging or destroying them. They imaged 250 seeds spanning 75 different species (some were also different genera), revealing the embryos and nutrient structures inside the seeds in exquisite detail. [Photos: Ancient Flowering Plant May Have Lived with Dinosaurs]

Around half of the fossil seeds they examined contained preserved cell structures within their seed coats, and about 50 seeds held partial or complete embryos. Once they had 2D images of the embryos, they used software to model the embryos' shapes in 3D, finding that their size and shape varied between seeds. In some cases, the embryos resembled those in modern plants believed to be distant relatives of the Cretaceous angiosperms.

"These observations give us new insights into the early part of the life cycle of early angiosperms, which is important for understanding the ecology of flowering plants during the emergence and dramatic radiation through the early Cretaceous," Friis said in a video statement.

During the Cretaceous period, angiosperms evolved and diversified rapidly. Many new insect species, which also appeared during the Cretaceous, may have played a part in how quickly flowering plants took hold and thrived in the ancient landscape.

Prior evidence from living and fossil plants has suggested that the earliest angiosperms grew close to the ground and took advantage of disrupted environments, and that they moved rapidly through growth stages. All of the seeds analyzed in the study were preserved during a dormant stage in their life cycle, the authors reported. The embryos were so tiny — less than one-fourth of a millimeter — that they would need to grow more inside the seed before they could germinate.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our discoveries support hypotheses based on extant plants that small embryos and seed dormancy are basic for flowering plants as a whole," Friis said. A dormant period for seeds meant that they could "wait out" a harsh environment and postpone growth until conditions were more favorable, a survival strategy practiced by many flowering plants today.

The findings were published online Dec. 16 in the journal Nature.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.