Sticky Amber Preserved Dinosaur-Age Insects for Millions of Years

During the age of the dinosaurs, three tiny mantises became engulfed in glops of sticky amber and stayed there, preserved, until researchers discovered the entombed critters millions of years later.

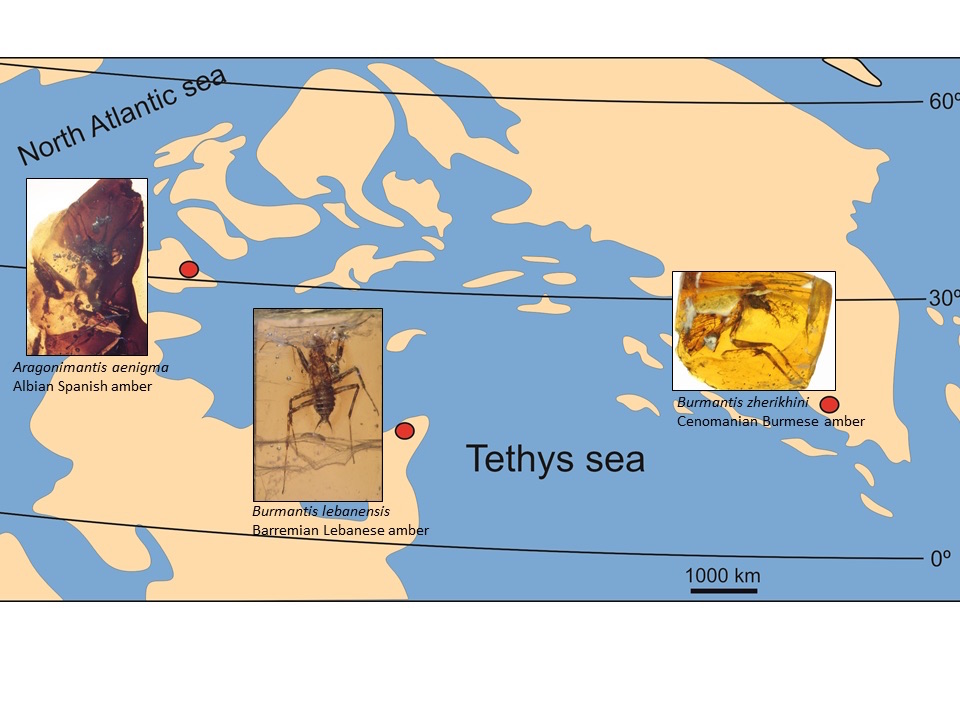

The three specimens — found in modern-day Lebanon, Myanmar and Spain — are helping scientists learn more about the diversity, family tree and geographic range of these ancient insects.

"The fossil record of mantises is very rare and fragmentary, with no more than two dozen species known worldwide," said study first author Xavier Delclòs, a lecturer of paleobiology at the University of Barcelona. "However, the few specimens found help us understand how the evolution of this group of insects is closely related to cockroaches and termites." [Image Gallery: Tiny Insect Pollinators Trapped in Amber]

Two of the three specimens are species that are new to science, and all of them date to the Cretaceous period (65.5 million to 145.5 million years ago), Delclòs said.

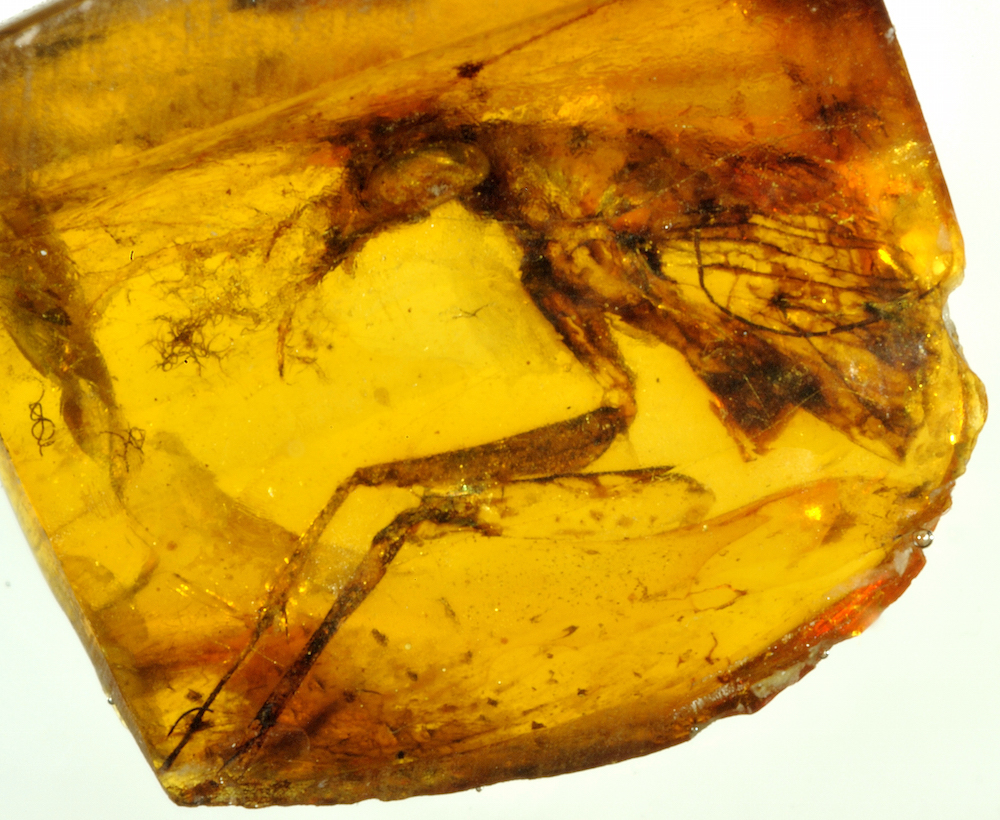

The mantis discovered in Myanmar (Burmantis zherikhini), one of the newly discovered species, is an adult. However, the 97-million-year-old specimen is incomplete, showing only its head, prothorax (upper midbody), left foreleg, a partial midleg and wing bases, the researchers said.

In contrast, the 105-million-year-old mantis discovered in Spain (Aragonimantis aenigma) is a nymph (young insect), and represents a new genus and species. It's the first record of a Mesozoic (an era encompassing the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods) mantis discovered in western European amber deposits, the researchers said.

However, the newfound A. aenigma specimen includes only the head and thorax, and measures about 0.3 inches (7 millimeters), excluding the antenna. The mantis also has mandibles with three teeth, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists already knew about the species found in Lebanon (Burmantis lebanensis). The newfound specimen is also a nymph, and its entire body is preserved, making it the most complete specimen of its species on record, the researchers said. This allowed them to examine its markings, preserved in the amber.

"The color pattern observed in B. lebanensis perhaps permitted it to protect itself by camouflage, both to avoid predators and to better snare their prey," Delclòs told Live Science.

In addition, at about 128 million years old, the 0.2-inch-long (4.5 mm) Lebanese mantis is "the oldest [mantis] species known in amber," Delclòs said.

All of the specimens have so-called "raptorial forelegs," which likely helped the insects catch and grip prey. But they aren't entirely like modern praying mantises, Delclòs said. For instance, the Cretaceous mantises don't have an ultrasonic "ear" on the metathorax (midbody) that helps today's mantises avoid bat attacks. (This ultrasonic feature developed in mantises during the Eocene, a period that lasted from 56 million to 33.9 million years ago.)

The new findings may be a "mixed bag," but "the new material further highlights the diversity of [mantises] during the Cretaceous and the importance of fossils, despite the paucity of material, for advancing knowledge of mantis evolution," Delclòs said.

The study will be published in the May 2016 issue of the journal Cretaceous Research.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.