Fowl Play: Diverse Parasites Infest Backyard Chickens

Why did the chicken cross the road? Opinions vary, but during her travels she likely picked up a few unwelcome hitchhikers, new evidence suggests.

While free-ranging urban hens enjoy more freedom and a more natural environment than their commercially raised sisters, a recent study hints that their enjoyment comes at a price. Chickens that live in backyards are exposed to a wider range of ectoparasites — parasites that live on the skin — than their commercial counterparts. In addition, many of those pests go unnoticed by the chickens' owners, the researchers found.

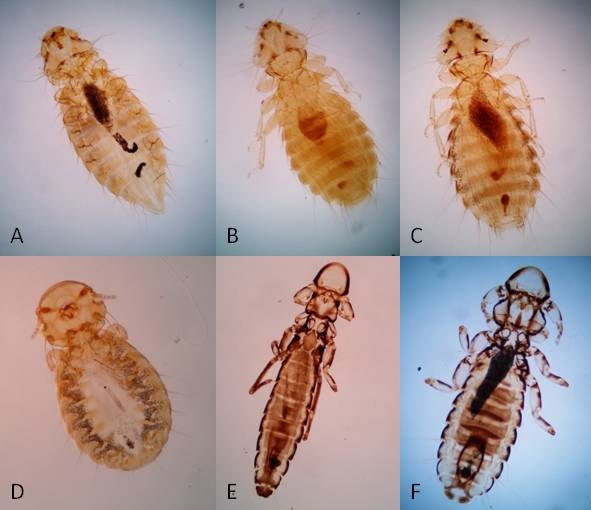

In a study published online Jan. 11 in the Journal of Medical Entomology, scientists investigated 100 hens from 20 flocks in Southern California, and found a number of parasites in the coops and on the birds that are typically absent in commercial farms. Many of the urban chickens were playing host to a diverse group of parasites, which included fleas, mites and six species of lice: Menopon gallinae, Menacanthus cornutus, Menacanthus stramineus, Goniocotes gallinae, Lipeurus caponis and Cuclotogaster heterographus. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

While commercially farmed chickens are more likely to have mites, lice were the most common pests found in the study of backyard chickens, with 85 percent of the birds hosting at least one of the six species. Among those six, M. stramineus was most abundant, found in 50 percent of the coops and on 36 percent of all the hens. In some cases, dozens or even hundreds of specimens were collected from individual birds. Researchers detected sticktight fleas, also known as stick fleas, on 18 percent of all chickens and in 20 percent of the coops examined in the study. Nearly one-third of the chickens studied were infested by two or more species of pests.

Roaming the yard and scratching in backyard dirt increases urban chickens' exposure to the parasites, many of which can also be carried and distributed by local wildlife, the study authors suggested. Chickens in commercial farms, usually confined to small wire cages, wouldn't come into contact with the immature stages of the parasites that live in soil. And their cages provide little opportunity for the parasites to hide.

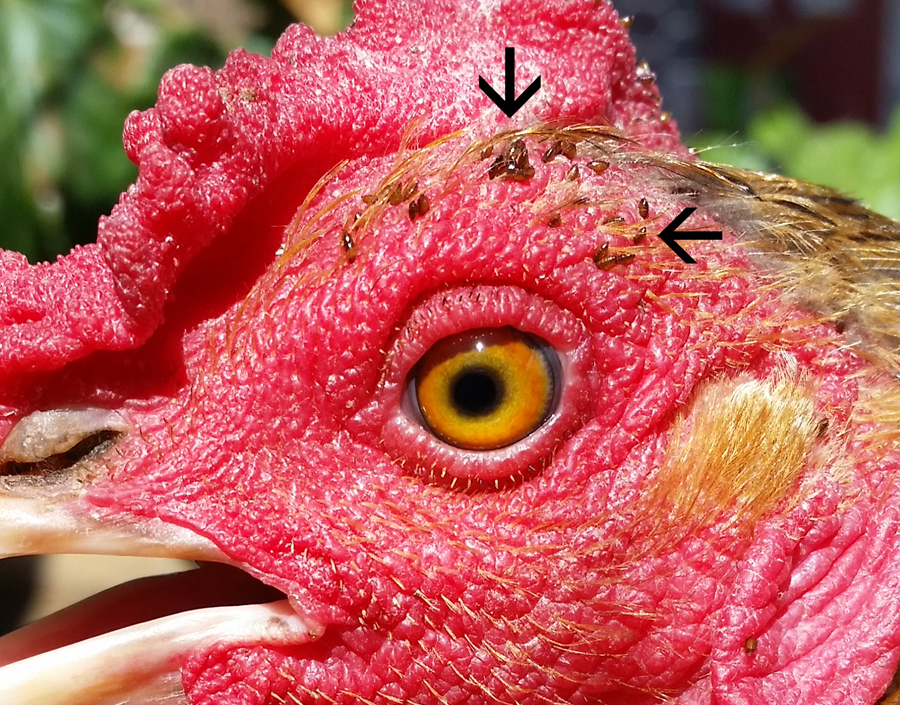

Sometimes the parasites are more visible, especially when they cluster around the hen's comb, like sticktight fleas often do. But parasitic interlopers like lice can be harder to locate. Unlike the fleas, which can also infest mammals, the lice are not only species-specific, but also thrive on specific body parts, like under the chicken's wing, head or near the rear end. The researchers ruffled plenty of feathers to find these bloodsuckers, searching under wings, around their necks and under their abdomens to collect stowaway arthropods.

Amy C. Murillo, a graduate research assistant with the Department of Entomology at the University of California, Riverside, and lead author of the study, told Live Science that, in some cases, the owners' very first encounter with the parasites took place during the scientists' backyard investigation. "In general, we'd part the feathers and they'd go, 'What is that?!' That's when we'd start educating on the fly and collecting whatever we found."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Teresa Micco is a veterinarian who treats about three to five chickens each week at the Point Vicente Animal Hospital in Rancho Palos Verdes, California. Micco, who was not involved in the study, said that she often sees the stick flea ectoparasite in her practice, "anywhere from small numbers, just a scattering on the head, to completely infested, where you can't even see the skin," Micco told Live Science. "I don't even like to see a few stick fleas on them, because if you see a few they can lay thousands and thousands of eggs very rapidly," Micco added.

So, what's a chicken owner to do? "The best way to prevent or control parasites is to keep their areas very clean," Micco said.

If urban chicken owners are unfamiliar with all the pests that could infest their birds, a scarcity of research in this area isn't helping. The authors cited studies of backyard flocks and their ectoparasites conducted in other countries, but added that theirs was the first survey of this type published in the United States. In fact, some of these lice species have never been studied in detail before, Murillo said.

Murillo hopes that her work will help fill this gap for the growing number of backyard chicken enthusiasts, helping them to detect and control pests targeting their flocks. "The Internet in general can be a scary place when you start looking up things like ectoparasites," Murillo said. "You find a lot of misinformation. So I think this would be a very good opportunity specifically targeted to chicken owners, to get some accurate scientific knowledge out there."

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.