Magnetic Device Lets Smartphones Test Your Blood

Smartphones equipped with portable devices that magnetically levitate cells might one day help diagnose diseases in the home, clinic or lab, researchers say.

Nowadays, smartphones are incredibly powerful portable computers that include handy devices such as multimegapixel cameras, and they can be found in both developing and developed countries. Increasingly, researchers are exploring ways for smartphones to be used not only for posting selfies and playing video games, but also to help save lives by rapidly performing medical tests anywhere there are smartphones — that is, virtually anywhere around the world.

A common medical test involves measuring the levels of red blood cells and white blood cells in the blood. Standard methods for classifying and counting blood cells are either complex and expensive or labor-intensive and time-consuming. Now, scientists have developed a lantern-size device that can measure blood-cell levels using magnetic levitation. They also say their invention can be combined with smartphones to carry out this medical test rapidly, easily and affordably. [10 Technologies That Will Transform Your Life]

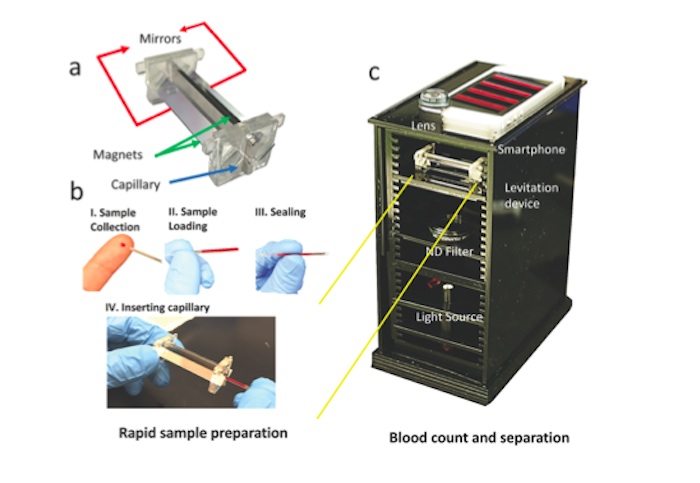

To use the portable imaging magnetic levitation system, dubbed i-LEV, a smartphone is placed on top of a lens so that the device's camera can look down on tubes filled with finger-prick-size volumes of blood — say, 30 microliters, or about the volume of a single grain of rice. Mirrors and an LED light help users see the specimens. The entire kit is about 6.3 inches by 4 inches by 7.9 inches (16 by 10 by 20.5 centimeters).

The blood samples are laced with a chemical known as gadobutrol, which is paramagnetic — that is, it is slightly attracted to magnetic fields. These samples are placed between two long, thin magnets about the size of toothpicks, and whatever is within buoys up in this magnetic field, the researchers said.

Cells float up to different heights in the magnetic field depending on their density, which, in turn, depends on their type. This helps the device easily separate red and white blood cells in about 15 minutes, the researchers said.

"Here, we develop a method to measure cell densities accurately at a single-cell level and separate them based on a balance between their weight and magnetic forces," said study co-author Utkan Demirci, a bioengineer at Stanford University.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The smartphone could see individual blood cells using i-LEV. Computer programs could then automatically count the number of blood cells seen in less than 30 seconds, the scientists explained.

Most portable biomedical devices designed to work with smartphones require extensive preparation of medical samples beforehand, and many need dyes and other labeling compounds to distinguish, for example, one cell type from another, Demirci and his colleagues said. In contrast, the researchers said i-LEV forgoes these steps and is therefore much simpler and easier to use.

The researchers noted that i-LEV could do more than just measure blood-cell levels. For example, their previous research found that cancer cells and infected cells levitate differently from the way healthy cells do. The invention could also help monitor the effects of drugs on cells for research applications.

The i-LEV is patented, and Demirci noted that it has already drawn lots of commercial interest. Still, "it won't be at the clinic the next day," Demirci said. "As with any other technology, this technology will take years of development and further commercialization to see it as a product on a shelf."

The scientists detailed their findings online in the journal Small on Nov. 2, 2015.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.