Hundreds of Tiny Bugs Are Probably Hiding in Your Home

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

No matter how well you think you know your home, it holds a number of dark corners and hidden spaces that you don't look at too closely from day to day. And more likely than not, these nooks and crannies host a vast range of tiny squatters that have somehow found their way in from outdoors, and in greater numbers than you might expect, according to a new study.

But don't panic. They really don't want to bug you.

Entomologists from North Carolina State University conducted an investigation to find out just how many different arthropods — insects, spiders and other invertebrates that have segmented bodies and jointed legs — might share homes with people. Many arthropod species — like termites, bedbugs and roaches — are known to live alongside humans, and to seek out these living spaces, generally bringing a measure of discomfort and inconvenience to their hosts. But no study before this one had ever tallied just how many varieties of nonpest arthropods end up in houses — often by accident — and then simply settle in. [See Photos: 15 Insects and Spiders That May Share Your Home]

Turns out, there are more of them than you'd think, and they're quite a diverse group.

The researchers visited and sampled homes within a 30-mile (48 kilometers) radius of Raleigh, North Carolina, collecting any living or dead arthropod that they found in attics, basements, bathrooms, kitchens, bedrooms and common areas. They discovered that each house could play host to many hundreds of arthropod species, with an average tally per home of about 100 species representing 62 arthropod families.

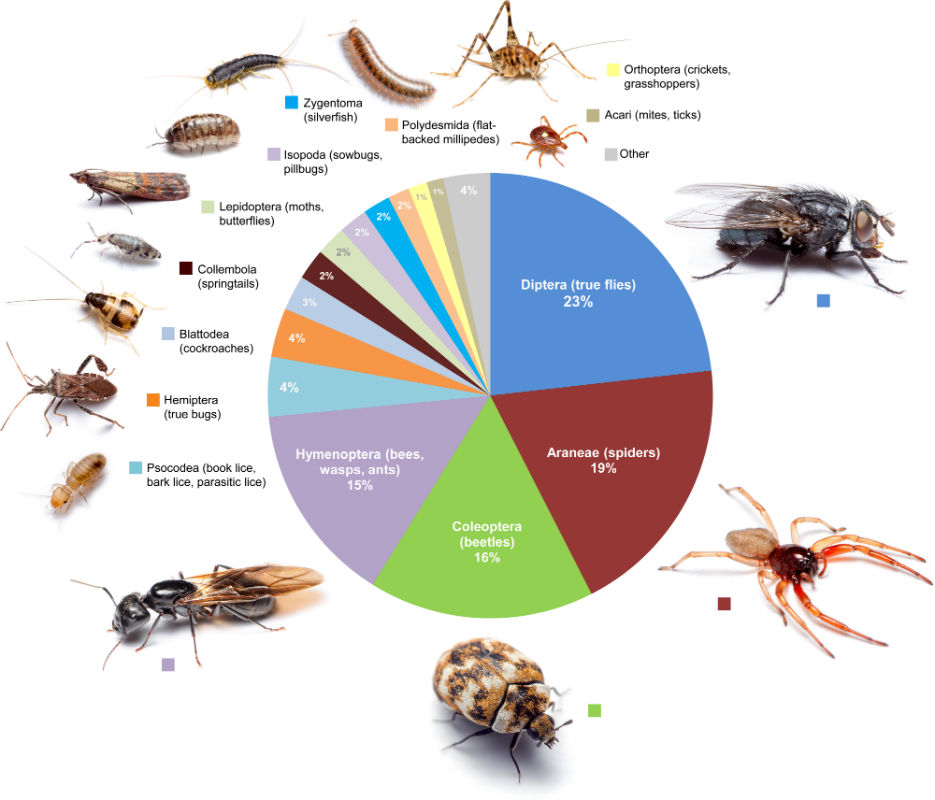

Many of the species they found will sound familiar to most people: Flies, beetles, wasps, spiders and ants were the species most frequently seen and collected, making up about 73 percent of all of the arthropods identified in the survey. Gall midges, tiny flies measuring about 0.04 inches (1 millimeter) long, were common indoor visitors, appearing in all of the homes investigated.

From all of the houses, the scientists compiled a list of 579 species from 304 families — and they say the list is probably far from complete. Michelle Trautwein, co-author of the study and the Schlinger chair of dipterology at the California Academy of Sciences, said in a statement that this represents just a "first glimpse" of the species that cohabitate with humans.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Matt Bertone, lead author of the study and an entomologist at the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic at North Carolina State University, told Live Science that a surprising number of people volunteered their homes for the survey; he and his colleagues gathered more than 400 responses within a couple of days. They eventually narrowed them down to 50, first making sure that participants understood that the scientists' goal was collection — not extermination, Bertone said.

The researchers conducted the survey between May and October, to zero in on arthropod groups that were likely to invade homes at any time, rather than those that move into houses when it turns cold outside, Bertone said.

To find the arthropods, a team of entomologists donned headlamps and knee pads, because they "learned early on that crawling around on the floor takes a toll on your knees," Bertone said. Armed with flashlights, tweezers and aspirators, they traveled from room to room, searching ceiling to floor, in closets and corners, in cut flowers and on potted plants, covering all areas that were easily visible. In one case, the homeowner's children came home early and pitched in to help with collection.

"And then, at the end of the process, we lined up all the vials and showed the homeowner, "'This is what your kitchen had in it; this is what was in your den, or your bedroom,'" Bertone told Live Science.

In most cases, the homeowners were startled to see the variety of arthropod life that the scientists uncovered. Bertone said this proves that these organisms are not only very small and isolated but also probably trying very hard to stay out of your way. [Gallery: Out-of-This-World Images of Insects]

If you're less than thrilled at the thought of these unexpected roommates, you'll be pleased to know that the researchers identified many of them as short-term visitors that arrived accidentally, won't survive very long and aren't likely to reproduce.

"The vast majority of what we did find were things that just wandered inside and died," Bertone said. "They may have little interactions with you — say, a moth flying in front of your face or a fly landing on your countertop, but they can't survive very long in the home."

They won't hurt you, either, the researchers added. Although many of the species that Bertone and his colleagues found were predatory — like spiders, centipedes, wasps and beetles — they can't bite people. In fact, some may actually help out around the house by consuming harmful species — the arthropod equivalent of pitching in with household chores.

Yes, your home likely contains a lot more residents than you may care to think about, but chances are good that you'll never see them. And those you do see aren't going to disturb you and may even do some good. "Just keep living your life how it is," Bertone advised. "This has been happening for a long time."

The findings were published online today (Jan. 19) in the journal PeerJ.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus