Fossilized Eyeballs Reveal Crustacean Had Incredibly Complex Sight

A mysterious 160-million-year-old crustacean had incredibly complex eyes similar to those of modern arthropods, a group that includes insects and other crustaceans, among other animals, a new study finds.

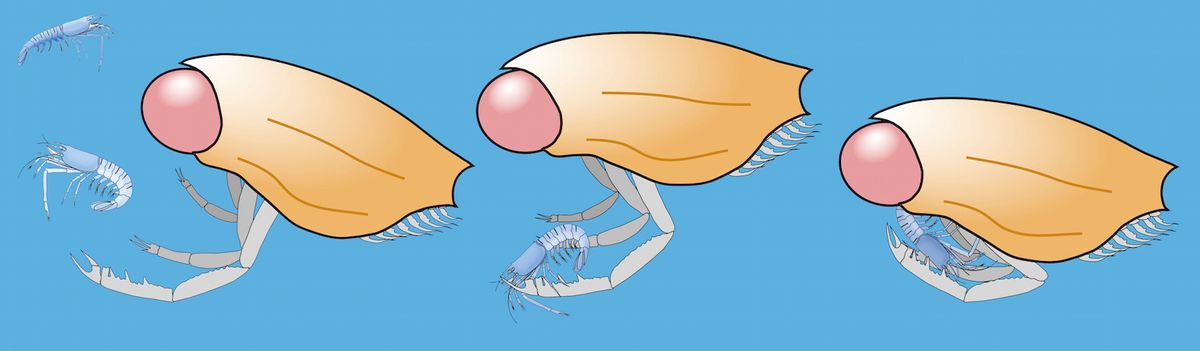

The ancient marine arthropod, known as Dollocaris ingens, likely used its exceptional vision to hunt, possibly as an ambush predator, the researchers said.

"It's a very weird creature, indeed," said study lead researcher Jean Vannier, a paleobiologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research in Lyon. "We found the remains of undigested shrimps in its stomach, and the animal had obvious [grasping] legs. No doubt, acute vision was essential in its daily life." [Fabulous Fossils: Gallery of Earliest Animal Organs]

Typically, Vannier studies creatures that lived during the Cambrian period (between 541 million and 485.4 million years ago), when many animal groups first appeared in the fossil record. Complex sight also evolved during this time, and was a real game changer for these organisms.

"When vision appeared, things changed dramatically," Vannier told Live Science. "Animals with eyes could detect prey more easily, and prey had to worry about it."

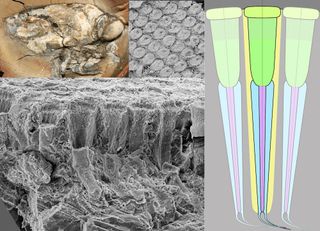

But scientists have yet to find a well-preserved eye with fossilized sensory cells from the Cambrian period, he said. So, Vannier and his colleagues turned to the D. ingens fossils dating back 160 million years, to the Jurassic period. The fossils were discovered in the 1980s in the La Voulte-sur-Rhone formation in southeast France, but they had not been properly studied until now, he said.

The eyes of D. ingens are a remarkable find, Vannier said. "Such exceptional preservation of an eye had never been observed in the fossil record, except in very recent fossil flies in amber," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Super Surpr-eyes

D. ingens belongs to an enigmatic extinct group of crustaceans called thylacocephalans, which don't resemble any modern crustaceans, Vannier said. He and his colleagues discovered its incredibly preserved eyes while examining the critter, which measures between 2 and 8 inches (5 and 20 centimeters) in length.

To study the creature's internal organs, they used X-ray microtomography, a technique that compiles X-ray cross-section scans to make a virtual 3D model. Then, they used a scanning electron microscope, which helped them discover the exceptional eyes.

The eyes make up nearly one-fourth of the animal's entire body, and each eye has about 18,000 ommatidia, tiny cylinders that make up a compound eye (think of a fly's eye). D. ingens has more of these cylinders, which contain a lens and light-receiving sensory cells, than any other modern arthropod except the dragonfly, which has about 30,000.

The size, shape and number of these ommatidia indicate that D. ingens had "acute vision, which normally characterizes predators" such as dragonflies and mantis shrimps, Vannier said.

The study was published online Tuesday (Jan. 19) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular