Explorer Henry Worsley has died of exhaustion and dehydration, just a few dozen miles short of completing his historic voyage across the ice of Antarctica.

"It is with heartbroken sadness, I let you know that my husband, Henry Worsley, has died following complete organ failure, despite all efforts of ALE [Antarctic Logistics and Expeditions] and medical staff at the Clínica Magallanes in Punta Arenas, Chile," his wife, Joanna Worsley, said in a statement.

The 55-year-old adventurer had traversed 913 miles (1,469 kilometers) of the continent alone and was just 30 miles (48 km) shy of completing Sir Ernest Shackleton's unfinished 1907 "Nimrod Expedition" across the coldest continent. After Worsley was airlifted, doctors discovered that he was suffering from peritonitis, in which the lining of the abdomen becomes infected. [In Images: Antarctic Explorer Robert Falcon Scott's Last Photos]

Many people are wondering why the tragedy occurred, given the meticulous planning and sophisticated tools Worsley had that his Antarctic explorer predecessors didn't. It turns out that all of the sophisticated technology available to modern-day explorers cannot completely erase the essentially dangerous nature of the place.

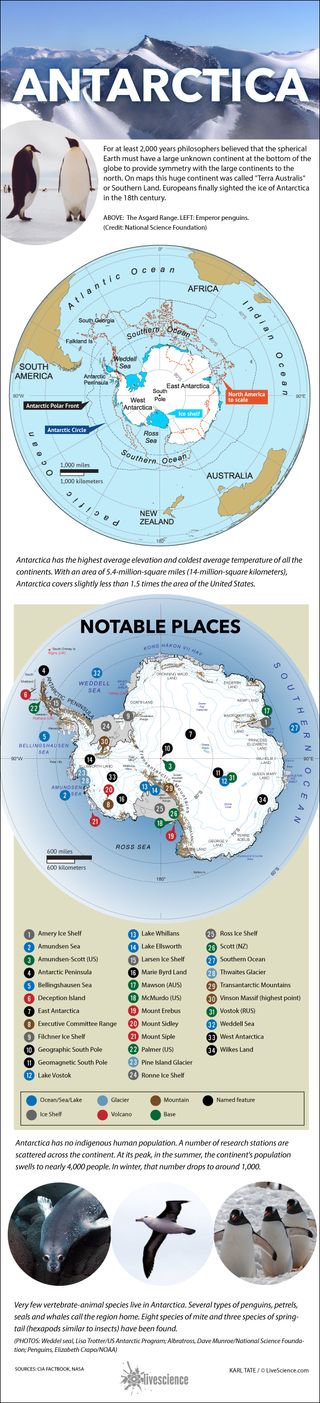

"Antarctica is the last wilderness on the planet," said Martin Siegert, a geoscientist and Antarctic explorer at the University of Bristol in England, who has led expeditions to Antarctica in the past. "There are no native humans living on Antarctica, and there's a good reason for that."

New technology, old limitations

So much has changed since Shackleton and his fellow ice explorers first set foot on the most southerly continent. Antarctic adventurers now have access to radio communications, state-of-the-art clothing, GPS devices and maps that are light-years better than the giant blank space Shackleton faced. In addition, people can be evacuated now within 12 hours, whereas Shackleton and his crew were completely on their own once the Endurance sank. What's more, thousands of people live on the ice for extended periods, at both the McMurdo Station and the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. [Extreme Living: Scientists at the End of the Earth]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's likely that every step of Worsley's voyage was meticulously planned and accounted for, from the likelihood of inclement weather or poor conditions, to his route, to the amount of food he carried, to his energy expenditure, Siegert said.

Yet, ultimately, all that planning and all of the advanced technologies at hand could only partially buffer against Antarctica's frigid conditions.

"You can't account for, and you can't train for, something like this," Siegert said.

Dehydration

Not surprisingly, Worsley's fiercest adversary was the bone-chilling cold. Average temperatures on the continent during this time of year dip to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 40 degrees Celsius), and people wear the ultimate extreme-weather gear. Worsley, who was pulling a sled, was engaged in incredibly arduous physical activity.

The combination of being bundled up and working so hard leads to a lot of sweating. For instance, when Siegert was working in Antarctica doing hard manual labor, his clothes would become sopping wet from the sweat, he said.

"It's like being in a sauna," Siegert told Live Science. "You're almost permanently dehydrated; you can't replace the liquids you give out."

Dehydration and exhaustion also impair thinking, leading a person to make irrational decisions and causing a dangerous downward spiral, Siegert added.

And although Worsley was surrounded with frozen water, melting that ice takes a lot of time and energy, so it may have been impractical for him to melt enough ice to drink while keeping up with other aspects of the journey, Siegert said.

Earlier warning signs

Worsley was using radio communications with a large support staff for safety purposes. What's more, once the decision was made to evacuate him, an Aleutian plane was able to reach him within 12 hours and fly him to get medical attention in Chile.

So, in this instance, the real issue was that Worsley, and those he communicated with, did not recognize how dire the situation had become until it was too late, Siegert said.

"When does a person realize that they cannot go on?" Siegert said. "That cannot be when they can no longer put one [foot] in front of another. That's far too late."

The people communicating regularly with Worsley could have noticed his judgment or ability was impaired well before he was airlifted, Siegert said. "The telltale signs should have been noticed," he said.

In fact, Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition provides a similar lesson, Siegert said. The calm, collected leader stopped 97 miles (156 km) before his ultimate destination of the South Pole. He actually stopped well before the true point of no return, having calculated that there was no way to make it back with all of his men alive if he were to have pressed onward, Siegert said.

Worsley's ill-fated trip may suggest that going it alone in the Antarctic wilderness is simply too dangerous an endeavor, Siegert said.

"It's such a feat of human endurance that maybe it's not possible to do this sort of thing," Siegert said. "Maybe you have to be so lucky with conditions that it's too risky and not worth doing."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular