As Zika Virus Rises, Vaccine Development Gets Attention

With fears of Zika virus reaching new heights — women in some countries, for example, are being advised not to get pregnant for years — all eyes are turning toward prevention.

And experts say that developing a vaccine will be one of the best ways to fight this virus.

"If a vaccine is feasible, it would be one of the best ways to combat [Zika virus]," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease specialist and a senior associate at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center's Center for Health Security. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Zika causes an infection that is usually mild, but officials are concerned that infections in pregnant women may lead to microcephaly in their children, a condition that affects the brain and severely affects a child's cognitive development. The virus was originally seen in Africa and Asia, but has spread in the last decade to Central and South America, and some Caribbean and Pacific islands. In recent weeks, health officials in El Salvador, Ecuador, Colombia and Jamaica have suggested to women that they avoid getting pregnant until more is known about the risk of microcephaly.

Because Zika virus hadn't previously been considered a public health threat, there hasn't been much research done on the virus, Adalja told Live Science.

However, that doesn't mean that a vaccine is unattainable.

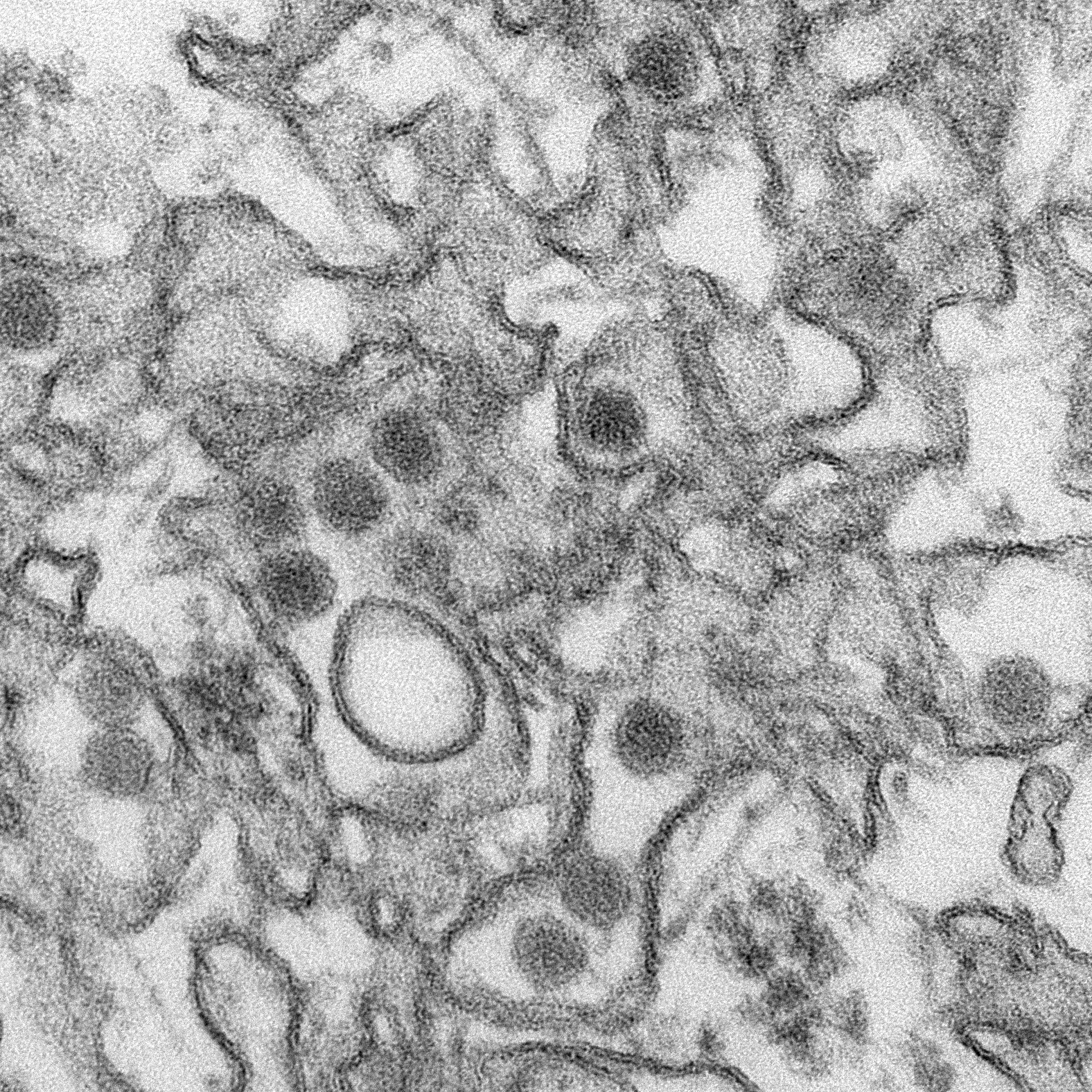

Although Zika virus is relatively new to the Americas, it's part of a family of viruses called flaviviruses, which includes more well-known viruses such as dengue, yellow fever and the West Nile virus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And there's a lot of existing research on other flaviviruses, Adalja said. For example, scientists have found ways to replicate human infections with these other flaviviruses in animal models, so that researchers can study how the infection progresses and test out possible drugs, he said.

Not only that, but scientists have a track record of success in making vaccines for such flaviviruses, which indicates that this family of viruses isn't completely impervious to vaccination, he said. There are currently vaccines against the flaviviruses that cause yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis, and these have paved the way for future vaccines against other flaviviruses, he said.

Still, as with any new vaccine, the first step for researchers is to devise a vaccine that triggers a response from the human immune system that can protect people from future infections, Adalja said. Then developers can move on to questions of side effects, cost and how long immunity lasts, he said.

And although the mutations that can occur in viruses over time can pose a problem, the goal of vaccine developers is to try and target a part of the virus that tends to not change, he said.

"All viruses mutate … so it's not a question of whether it mutates" but how stable Zika virus is in Brazil, for example, Adalja said. In other words, does it look like the virus is mutating quickly? Some clues to this might be found by sequencing the genetic material of a virus strain in Central America, and comparing it to the sequences of strains in other outbreaks in Asia and Africa, he said.

Adalja said that, for the time being, research on a vaccine would likely take priority over looking for drugs that can treat people infected with the virus.

Once a woman is infected with Zika virus, and the virus is in the blood, it can cross the placenta and affect the fetus, he said. It would be very hard to make an antiviral drug that could be administered fast enough to prevent the virus's effects, he said.

Follow Sara G. Miller on Twitter @SaraGMiller. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.