In Images: Drones Take Flight in Antarctica and the Arctic

Aerial drones are seemingly everywhere these days —even in Antarctica. But only on highly regulated missions conducted by scientists who hold pilot certification reflecting months of training. Guy Williams, a polar oceanographer at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania in Australia, trained for months before he received pilot certification and permission to test several models of aerial drones in polar environments, capturing images that scientists will use to develop satellite tools for mapping changes in sea ice. [Read full story about how drones are being used in some of the most remote locations]

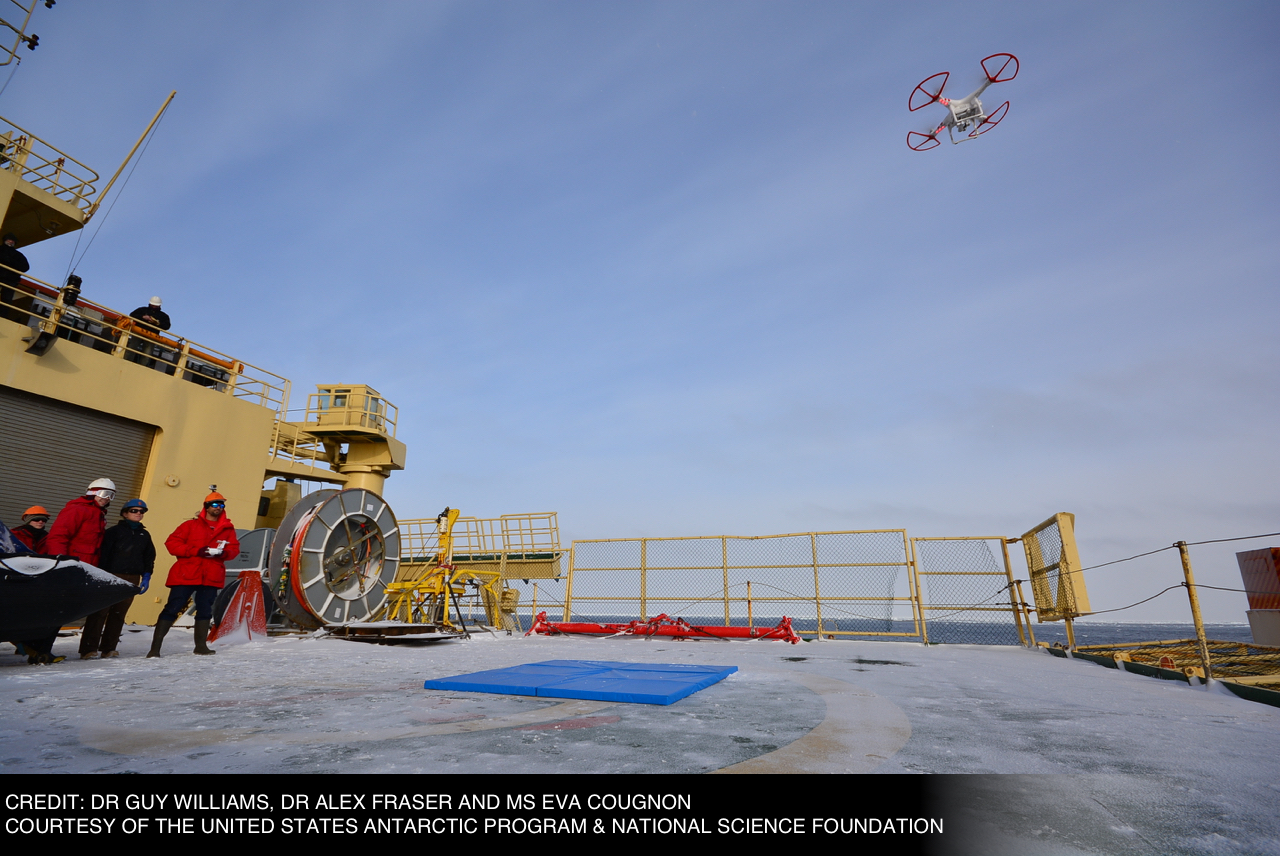

Pilot program

Testing the DJI Phantom 2 Vision+ aerial drone from the deck of the research vehicle Nathaniel B. Palmer, in Antarctica. This quadcopter was one of two drone models that polar oceanographer Guy Williams brought on the voyage as part of a pilot program to determine whether the drones could be operated safely in polar environments. (Credit: Guy Williams/Alex Fraser/Eva Cougnon, Courtesy of the U.S. Antarctic Program and National Science Foundation)

Sky and sea

An aerial view of the research vehicle. Winds presented a particular challenge to the researchers, and were often too strong for them to launch the drones. (Credit: Guy Williams/Alex Fraser/Eva Cougnon, Courtesy of the U.S. Antarctic Program and National Science Foundation)

Up, up and away

Guy Williams pilots the DJI S1000 Spreading Wings aerial drone in Antarctica, from the deck of the Nathanial B. Palmer. The drone uses 8 propellers and is capable of carrying up to 24 pounds (11 kilograms), according to the manufacturer. Williams was the only team member certified to pilot the drone. (Credit: Guy Williams/Alex Fraser/Eva Cougnon, Courtesy of the U.S. Antarctic Program and National Science Foundation)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Flying high

A view of Antarctic sea ice, taken by the S1000+ aerial drone. The winds in Antarctica rarely dropped below 23 miles per hour (37 km/h), which limited the amount of time that Williams could spend flying the drones. The researcher said the drone became difficult to control in wind speeds of more than 12 miles per hour (19 km/h). (Credit: Guy Williams/Alex Fraser/Eva Cougnon, Courtesy of the U.S. Antarctic Program and National Science Foundation)

Ice, ice, baby

A view of Antarctic sea ice from a distance of about 327 feet (100 meters), captured by the S1000+ aerial drone. (Credit: Guy Williams/Alex Fraser/Eva Cougnon, Courtesy of the U.S. Antarctic Program and National Science Foundation)

Off to a flying start

In the Arctic, Guy Williams piloted the DJI Phantom 3 Advanced aerial drone. Based on the success of drone test flights in Antarctica, when Williams and the rest of his team traveled to the Arctic in late 2015, they were operating as part of the science program. (Credit: Toshi Maki and Guy Williams)

Cleared for takeoff

The DJI Phantom 3 Advanced aerial drone, which carries an integrated camera, during one of its Arctic flights. "We try to use what comes off the shelf, so we can readily replace it," Williams told Live Science. (Credit: Toshi Maki and Guy Williams)

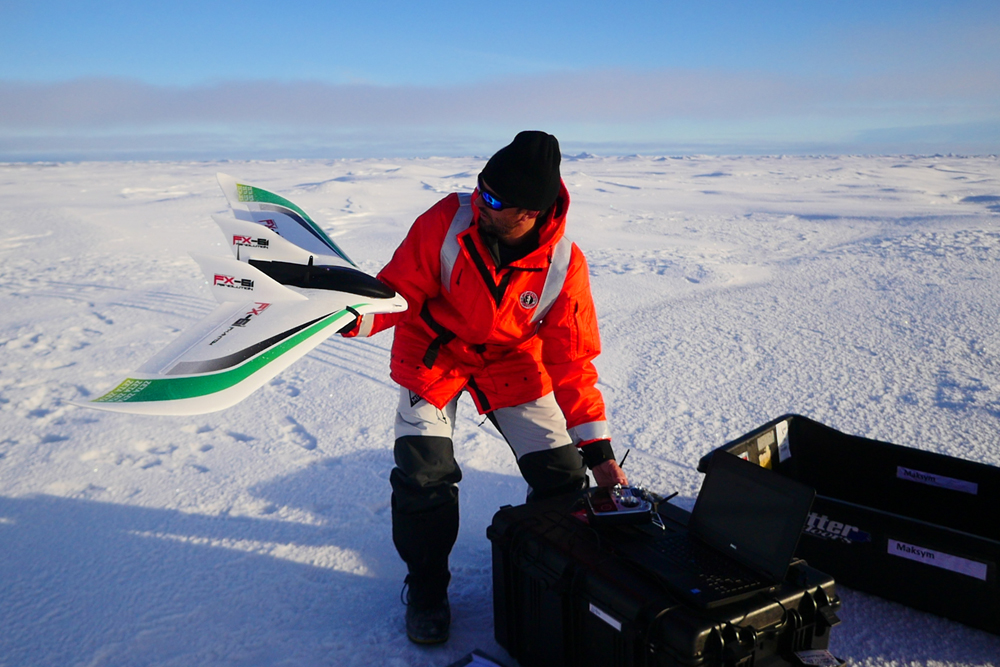

Ready to launch

Guy Williams launching the FX-61 Phantom Flying Wing, a fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that resembles a small airplane. "We were collecting the aerial imagery and the surface topography maps in conjunction with an underwater vehicle, plus other sea ice studies that were occurring on the surface," Williams said. (Credit: Toshi Maki and Guy Williams)

A mosaic of ice

The drone prepares for a net-based landing on the research ship. "With autonomous platforms above and below the ice, we can expand our coverage and make much more meaningful observations to test the satellites," Williams told Live Science. (Credit: Toshi Maki and Guy Williams)

Ready to fly

Williams and the FX-61 fixed-wing drone. (Credit: Toshi Maki and Guy Williams)

Arctic sun

Williams and the team prepare the FX-61 for its next flight. Using the camera-carrying UAV, Williams produced a photo mosaic of a sea ice field, a process that uses about 500 to 1,000 images to cover an area measuring about 5,400 square feet (500 square meters). (Credit: Toshi Maki and Guy Williams)

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.