How Zika Virus Spreads: Chain of Events Explained

Zika virus is "now spreading explosively in the Americas," World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Dr. Margaret Chan said on Thursday (Jan. 28), and 3 million to 4 million people in the Americas could be infected by the virus this year alone, according to the latest WHO estimates.

However, U.S. officials have said that the virus is likely to cause only small outbreaks in this country.

Officials' main concerns about the virus are over its possible links with two severe conditions: microcephaly, which is a birth defect that causes a baby to be born with a small head and brain and face lifelong cognitive impairments, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, a condition in which the immune system attacks the nervous system, sometimes leading to paralysis in children and adults.

To understand how the Zika virus spreads to new regions, and how researchers can tell whether a region is likely to experience large outbreaks or small ones, Live Science asked the experts what sequence of events has to happen in order for the virus to become established in a new region. Here's what they said:

How exactly do mosquitos spread the virus?

The Zika virus is spread by certain species of mosquitoes in the Aedes genus, most often the species Aedes aegypti. For local transmission to occur in a new region, for example in the United States, a female A. aegypti mosquito in the United States would have to bite a person who became infected with the Zika virus abroad, and then came to the U.S. The person would have to have active virus in his or her blood. Then, that same female mosquito would need to bite someone else, and expose that person to the virus.

Humans who are infected with Zika have sufficient amounts of the virus in their bloodstreams to infect a mosquito that bites them for anywhere from three to 12 days after they are initially infected, said Laura Harrington, a professor and chair of the entomology department at Cornell University in New York, who has studied the Aedes aegypti species of mosquitoes. [Zika Virus FAQs: Top Questions Answered]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After that bite, it can take approximately 10 to 15 days (depending on the outside temperature) before the female mosquito can transmit the virus to the next person, Harrington said.

Slightly more than 30 cases of the virus have been reported to date in the United States, all of them considered "travel-related," said a spokesman for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Americans who have contracted the virus were infected while traveling overseas, but there have been no cases of Zika virus being transmitted inside the United States to a person who has not been traveling, which would be called local transmission.

The mosquito can't immediately infect another person, because the virus typically first enters the mosquito's gut when the insect bites someone, Harrington said. From there, the virus infects the mosquito's gut tissue and a variety of other organs, taking days to make its way to the mosquito's salivary glands, from where the virus can be injected into the next host that the mosquito bites, she explained.

But once a female mosquito has the Zika virus in her salivary glands, and is capable of transmitting it to humans, the insect is able to do so for the rest of its life, Harrington told Live Science. Her research has found that such a female mosquito tends to live about 15 days.

Parts of the United States, especially the southernmost states, have A. aegypti mosquitos. This species is considered aggressive, prefers to bite people during the day, and can live both indoors and outdoors. People cannot catch the Zika virus by being around an infected person. [The 9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth]

Only two countries in the Americas — Canada and (continental) Chile — do not have the species that can spread the virus, according to the WHO.

Another unique quality of this mosquito species is that it feeds once every other day on human hosts, which is more often than other mosquito species do.

"This is really unusual and significant, because it leads to much greater potential for this mosquito to infect the people it feeds on, more so than any other mosquito," Harrington said.

A. aegypti has the ability to use human blood for both energy and egg production, and that makes this mosquito more fit, Harrington said. And a fitter mosquito means that it can live longer, breed more and infect more people with the Zika virus.

Concerns about U.S. spread

Some infectious disease experts say it's only a matter of time before the continental United States sees small outbreaks of Zika that involve local transmission of the virus on U.S. soil.

So far, the CDC has issued an interim travel advisory that currently affects 24 countries and territories where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. These locations are Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Martin, Samoa, Suriname, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Venezuela, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

But local transmission of Zika virus will probably happen in the U.S. this spring or summer, said Dr. Peter Hotez, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

The Gulf Coast of the United States is especially vulnerable to the spread of Zika virus as warmer weather approaches from May through September, when mosquitoes are most active, Hotez said. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

The Gulf Coast — which runs from western Florida, through the southern parts of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas — has two Aedes species of mosquitoes known to carry the Zika virus, as does Tucson, Arizona, Hotez said.

The extreme poverty in some locations along the Gulf Coast may make individuals in this region more prone to a Zika outbreak, he said. Some residents might lack screens on their windows and doors to protect against mosquitoes, and some areas have inadequate garbage collection, meaning discarded tires and containers may become reservoirs for standing water that attract mosquitoes to breed, Hotez told Live Science.

He said his overwhelming concern with the Zika virus relates to its possible link to the cases of microcephaly showing up in some babies born to mothers in areas of Brazil, Hotez said.

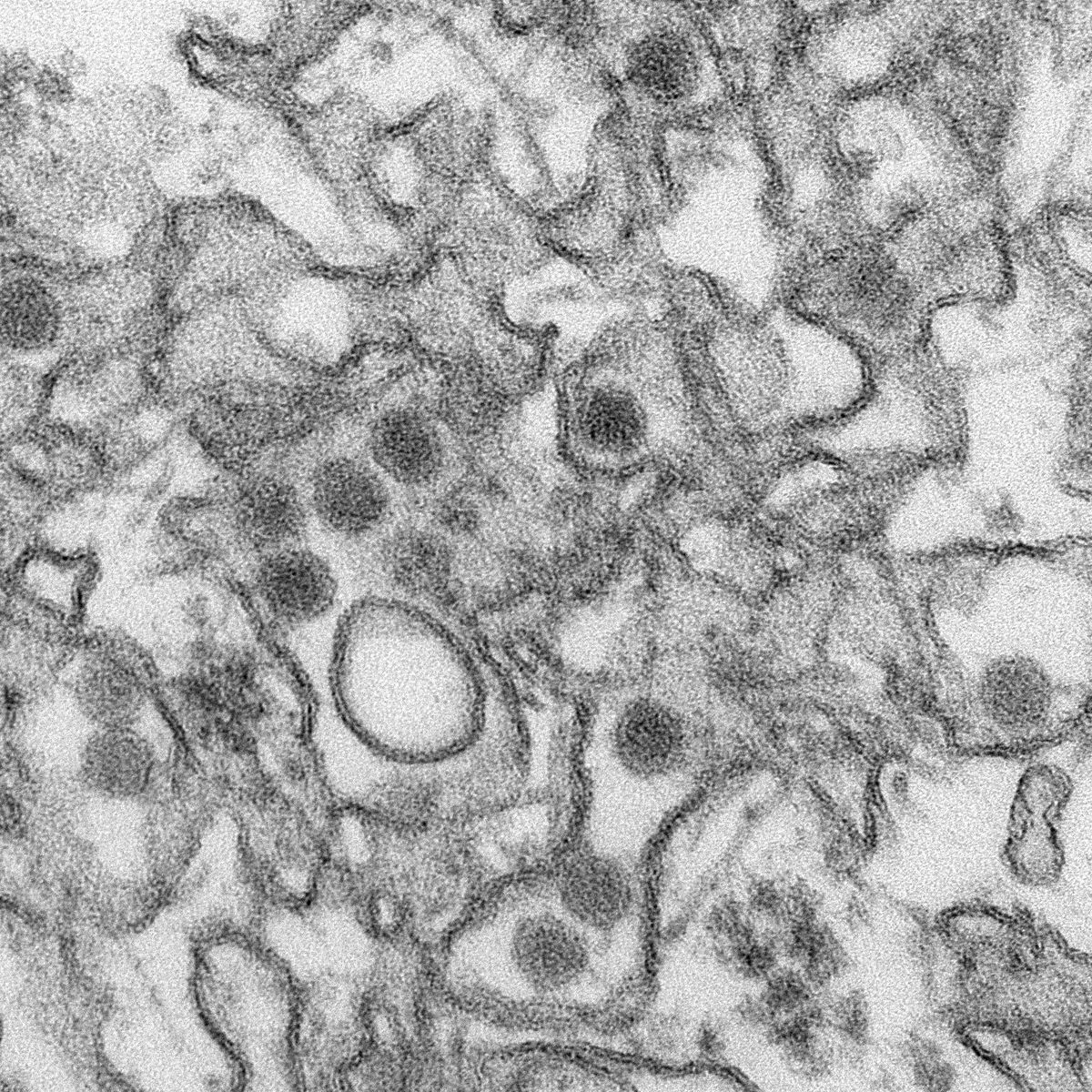

The exact mechanism for how the virus may lead to this birth defect is not known. However, one plausible explanation is that the virus gets into a pregnant woman's blood after she has been bitten by an infected mosquito, is transferred to the placenta, and then invades and damages brain cells in the developing fetus, Hotez said.

The United States will continue to see an increase in cases of Zika virus that are travel-related, and some of those infected people will be pregnant women, predicted Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

He said he also suspects the U.S. will very likely get some "bursts of localized transmission," of Zika virus, however, not widespread transmission of the infection.

"We have the Aedes species of mosquito in the U.S.," Schaffner said, and local transmission is most likely to occur in Southern states, he predicted.

But Schaffner said that it is very unlikely that Zika virus will establish itself in the same way that it has rapidly spread in South and Central America. "People in the U.S. spend more time indoors in air conditioning than people do in Central America and the Caribbean," he said. (Using air conditioning is a preventive strategy recommended by the CDC to limit mosquito exposure.)

However, tracking the virus' spread is going to be difficult because many people who become infected do not develop any symptoms, Schaffner noted. About 80 percent of people infected with Zika virus get no symptoms. And people who do develop symptoms typically have mild ones, such as fever, rash, joint and muscle pain, red eyes and headaches. These symptoms may last a few days to a week.

"It's basically a transient illness, but the two central nervous system complications — the microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome — are both serious consequences that are extremely concerning," Schaffner said.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.