Gallery: Erect Arachnid Penis Trapped in Amber

A 99-million-year-long erection? Well, sort of: Scientists discovered a spider relative trapped in amber, with its erect penis preserved. Here's a look at the male daddy longlegs in all its glory. [Read the full story on the ancient daddy longlegs]

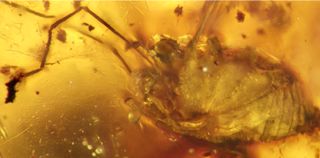

Ancient arachnid

An ancient harvestman, or daddy longlegs, trapped in amber and displaying an erect penis. Living harvestmen have mammal-like penises that stay tucked in their bodies until it's time to mate. This ancient species, Halitherses grimaldii, was found in Burmese amber from the Hukawng Valley in northern Myanmar. It dates back to the Cretaceous, 99 million years ago. (Photo Credit: Jason Dunlop et al., The Science of Nature, DOI 10.1007/s00114-016-1337-4)

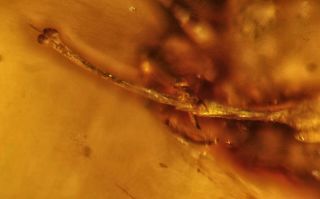

Harvestman penis

A close look at the erect harvestman penis found trapped in amber in Myanmar. This spider relative would have walked alongside dinosaurs. It may have been mating when it became trapped in sticky tree resin … or its death throes may have raised its blood pressure, causing an erection. Whatever the reason, this fossil is the first in amber to reveal an erect harvestman penis. (Photo Credit: Jason Dunlop et al., The Science of Nature, DOI 10.1007/s00114-016-1337-4)

Penis in proportion

A look at the size of the harvestman's penis in relation to its tiny body.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

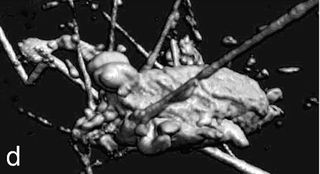

Arachnid eyes

A front view of the entombed harvestman using computed microtomography, a microscopic version of the CT scanning one might find in a hospital. The harvestman's spindly legs are visible, while the bulging structure visible in the middle upper third of the photograph shows the spider's large eyes. (Photo Credit: Jason Dunlop et al., The Science of Nature, DOI 10.1007/s00114-016-1337-4)

Side view

A side view of the harvestman fossil. The arachnid's body was just over 2 millimeters long. Its penis shape matched nothing seen in modern harvestmen, so researchers suspect that it belongs to its own now-extinct family of the arachnids. (Photo Credit: Jason Dunlop et al., The Science of Nature, DOI 10.1007/s00114-016-1337-4)

Harvestman from below

A computed microtomography view of h. grimaldii from below. The phallus is the curved structure protruding from the abdomen, marked by an arrow. There have only been 38 fossils of harvestmen discovered, and this is the first to display a penis. A private collector sent this fossil to researcher Jason Dunlop and his colleagues at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berline for study. (Photo Credit: Jason Dunlop et al., The Science of Nature, DOI 10.1007/s00114-016-1337-4)

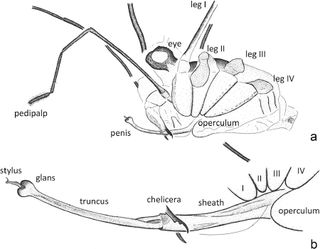

Illustrated arachnid

An illustration of the fossilized harvestman shows the labeled parts of this arachnid. The pedipalp is a non-leg appendage that protrudes from near the arachnid's head, allowing it to grasp objects. "Operculum" refers to a structure that covers bodily openings. Below, the parts of the penis are labeled from base to tip: Sheath, chelicera, truncus, glans and stylus. (Photo Credit: Jason Dunlop et al., The Science of Nature, DOI 10.1007/s00114-016-1337-4)

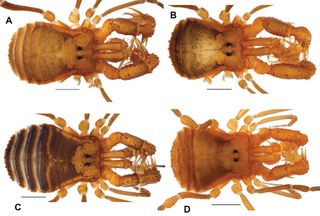

Behemoth of Oregon

A newfound daddy longlegs would have dwarfed this pipsqueak fossil harvestman. A living harvestman, now dubbed Cryptomaster behemoth (b and d), was discovered lurking in the leaf litter of an Oregon forest. Described in the Jan. 20, 2016, issue of the journal Zookeys, the harvestman sports a 0.15-inch-wide (4 millimeters) body. The species joins its close cousin, C. leviathan (shown in a and c), in the genus Cryptomaster. (Photo Credit: Starrett et al, Zookeys 2016) [Read the full story on this Oregon behemoth]

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.