New Pressure Sensor Could Help Detect Breast Tumors One Day

A new transparent, bendable pressure sensor could be incorporated into a pair of latex gloves and one day help doctors check women for breast cancer, without requiring X-rays, researchers say.

Doctors often touch and feel patients' bodies, applying small amounts of pressure with their hands, when assessing patients' health. For instance, any hard spots or lumps may be a sign of abnormalities such as tumors.

In fact, doctors may rely heavily on their "tactile feeling" of a patient's body to figure out whether the person may have cancer, said study senior author Takao Someya, a professor of electrical engineering at the University of Tokyo.

Pressure sensors could help doctors analyze their patients' health with greater precision than is possible with their natural sense of touch, the researchers said. "Tumors are normally more rigid than breast tissue, so we can input that data to a sensor-attached glove," Someya told Live Science.

However, because human bodies are generally soft, sensors that touch bodies must be soft too, in order to work well. But so far, pressure sensors that are soft have been vulnerable to bending, and these devices could not distinguish their own bending from the variations in pressure in the object they were supposed to measure, the researchers said.

"Many groups are developing flexible sensors that can measure pressure, but none of them are suitable for measuring real objects, since they are sensitive to distortion," study lead author Sungwon Lee, also of the University of Tokyo, said in the statement. [10 Technologies That Will Transform Your Life]

Now, the scientists say they have developed an ultrasensitive transparent pressure sensor that can accurately detect pressure even when the sensor is distorted to an extraordinary degree.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

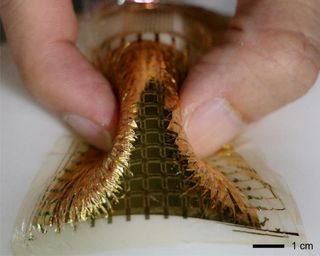

The researchers made the sensor from composite fibers containing graphene, which are sheets of carbon just one atom thick, and carbon nanotubes, which are carbon pipes only nanometers (billionths of a meter) in diameter. They took meshes of these pressure-sensitive, 300-to-700-nanometer-wide fibers and embedded them in thin, light, transparent, elastic plastic sheets.

When this flat sensor is bent, the nanofibers can shift around in the spaces inside the mesh, so their sensor capabilities do not change much even when the sensorsare bent to an extreme degree. However, the sensor can still respond when compressed by pressure.

In experiments, the device successfully measured pressure even when it was placed on the soft, movable 3D surface of a balloon that researchers pressed their fingers into. In addition, when the scientists wrapped their sensor around an artificial blood vessel made of plastic and filled with water, they found that "it could detect small pressure changes," as well as how fast the pressure was changing, Lee said in the statement.

The researchers noted that it was too early to suggest that pressure-sensitive gloves could replace mammography, which uses X-rays to diagnose and locate breast tumors. Still, one day, "the new sensors may offer easy and painless monitoring of tumors without exposure to radiation," Someya said.

This new sensor could also make robots sensitive to pressure, Someya said.

"Imagine that you are shaking hands with a robot that has soft skin," Someya said. "Currently, there is no pressure sensor that accurately works" once it is bent, he said. If the pressure sensor malfunctions, shaking hands with such a robot could be very dangerous, since the robot might end up accidentally crushing a person's hand.

In the future, the researchers want to design a stretchable pressure sensor that can accurately detect pressure even when the device is stretched, Someya said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 25 in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.