Early Bird or Night Owl? It May Be in Your Genes

If no amount of coffee seems to help you feel fresh and alert in the morning, you may be able to blame your genes.

According to a new study by the genetics company 23andMe, the preference for being a "morning person" — someone who enjoys waking up early and going to bed early — rather than being an "evening person," who tends to stay up late at night and desperately reaches for the snooze button when the alarm goes off in the morning, is at least partially written in your genes. Researchers at the company found 15 regions of the human genome that are linked to being a morning person, including seven regions associated with genes regulating circadian rhythm — the body's internal clock.

"I find it interesting to see how genetics influences our preferences and behaviors," said study co-author David Hinds, a statistical geneticist at 23andMe, a privately held genetic testing company headquartered in Mountain View, California. [7 Diseases You Can Learn About from a Genetic Test]

Circadian rhythms are roughly 24-hour cycles of activity controlled by the brain that tell our bodies when to sleep and help regulate other biological processes. Disruptions to the cycle contribute to jet lag and have been previously implicated in sleep disorders, depression and even obesity, according to Hinds. But until recently, research on circadian rhythms has been limited to experiments in animals and a few small studies in humans, he said.

For their study, Hinds and his team collected data from nearly 90,000 customers who submitted DNA in saliva samples. The researchers then asked the participants to answer a simple question: whether they consider themselves a morning person or a night person.

By comparing the survey responses with information from the participants' DNA, the scientists were able to analyze whether any single base-pair mutations — called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs — showed up more frequently in people who identified themselves as being a morning person.

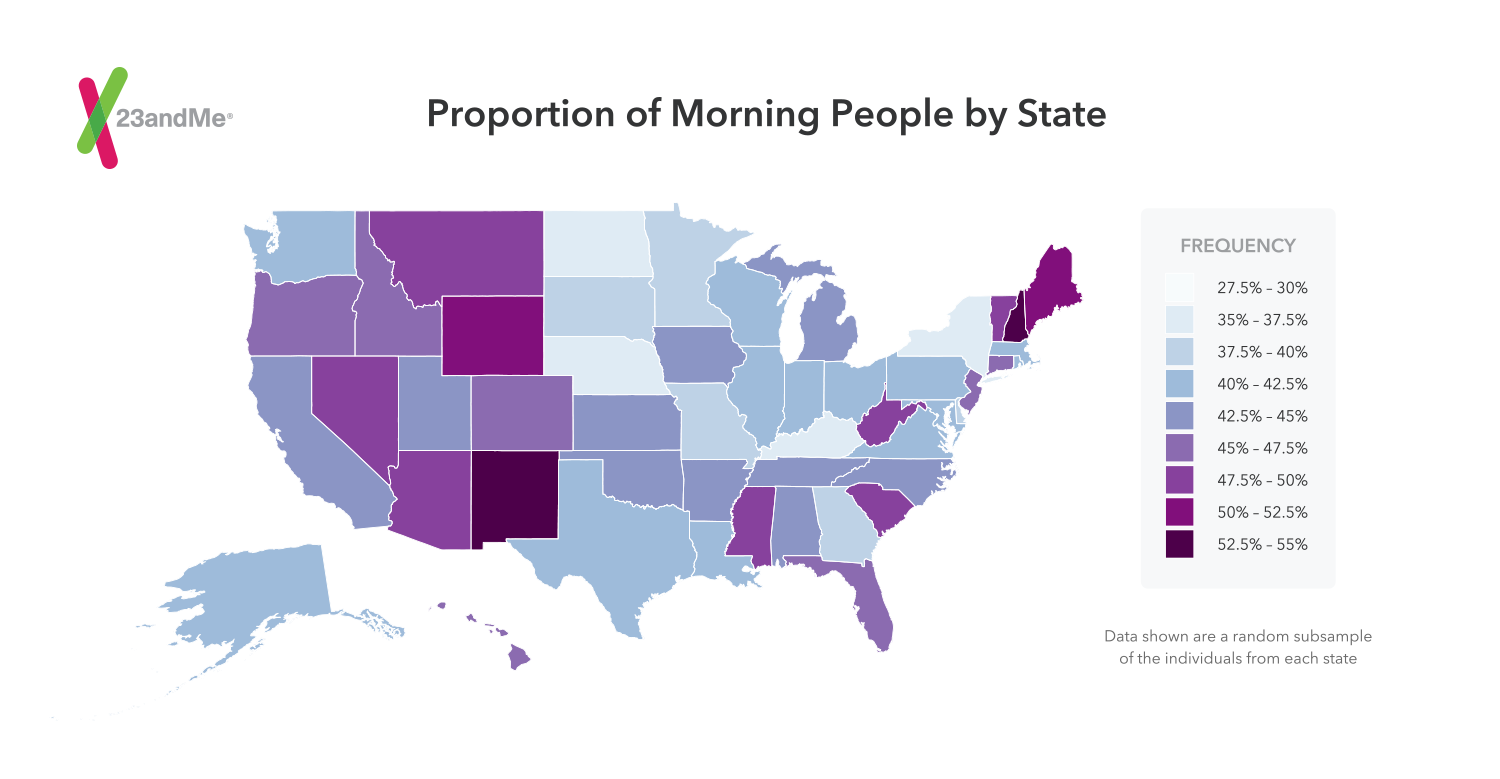

The scientists found that having one of 15 genetic variants increased a person's chances of being a morning person by between 5 percent and 25 percent, according to the study. Women were more likely to be early risers (48.4 percent, compared with 39.7 percent of men). And people over 60 said they preferred mornings more than those under 30 (63.1 percent, compared with 24.2 percent of participants under age 30), the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the distinction between being a morning person or an evening person isn't quite so simple, according to Till Roenneberg, a professor at Ludwig-Maxmilian University in Munich, Germany, who studies circadian rhythm.

"It is a continuous trait, as is body height or shoe size," Roenneberg told Live Science. "There aren't two shoe sizes and there are not just two body heights. It’s a continuum. There are very, very short people, very, very tall people, and the rest are in between."

How circadian rhythm manifests itself depends on a number of factors, such as sunlight and temperature, as well as genes, Roenneberg said. Although it can be assessed by certain questionnaires, simply asking people whether they consider themselves morning or night people will not provide an objective chronotype, he added.

Moreover, circadian rhythms are adaptable. That's what allows people to recover from jet lag, or work as flight attendants and shift workers, Roenneberg said. Being born with a predisposition toward waking early or sleeping in may make it more difficult for people to change their circadian rhythm. But, changing life circumstances and exposure to light — such as sitting in front of a computer in an office late at night, or going for a hike on a vacation — can change whether someone is a morning person or a night person, according to Roenneberg.

Geneticists, however, say that a large study like this could help boost researchers' confidence in the statistical significance of the genetic impact on circadian rhythms. "Despite all the other contributors to variation [in chronobiology], the genetic effect still shines through," Jun Li, a geneticist at the University of Michigan who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

But the study results don't prove that these genetic variants cause sleep disorders, depression or obesity just yet. That would take further research in other populations, as well as animal studies, to confirm a causal relationship, Li said.

Nevertheless, it shows that sleep is important to our health, said study co-author Youna Hu, a data scientist who recently moved from 23andMe to Amazon.

"This study provides some useful evidence and guidance for researchers to know where to poke more," she said.

The findings were published Feb. 2 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Knvul Sheikh on Twitter @KnvulS. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.