Defeating Zika: The Big Questions Researchers Are Trying to Answer

At least a dozen research groups are now working on developing a Zika virus vaccine, according the World Health Organization (WHO). But scientists are also investigating many more questions about Zika, beyond how to fight it with vaccination.

A licensed vaccine is likely years in the future, WHO representatives said. More-immediate questions will need to be addressed in order for scientists and health officials to diagnose and contain the virus in the meantime, and to determine whether Zika is linked to microcephaly — a disorder in which babies are born with smaller-than-average heads — and Guillaine-Barré syndrome, a neurological disorder.

Live Science has rounded up some of the biggest questions about this mysterious virus, and talked to experts to get the low-down on the latest science that might provide answers. Here is what we found: [Zika Virus News: Complete Coverage of the 2016 Outbreak]

Is Zika causing microcephaly and Guillain-Barré?

Perhaps the most urgent question is whether Zika is, in fact, causing babies to be born with the congenital condition microcephaly, and whether the virus is leading to the neurological disorder Guillain-Barré.

Microcephaly is rare, and growing clusters of infants with the condition in Brazil have been linked to areas with Zika outbreaks, suggesting a connection. The presence of Zika DNA in amniotic fluid in several of these cases indicates that the mothers were infected with the virus, which likely had come into contact with the developing fetus. Similarly, Guillaine-Barré, a rare condition that can cause near-complete paralysis in extreme cases, has been on the rise in areas identified as Zika hotspots in Brazil.

On February 10, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) described four cases — two microcephalic births and two miscarried fetuses — with signs of Zika infection in their brains and placental tissue, the strongest evidence yet of a connection between the virus and the birth defect. But scientists have yet to find the "smoking gun" that proves Zika infection is causing either microcephaly or Guillain-Barré, said Nicholas Jackson, global head of research for vaccine development at Sanofi Pasteur, one of the companies working on a Zika vaccine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's critical to confirm the potential association," Jackson told Live Science. "And there's another really important point related to that: If you get Zika and you don't have symptoms — because only one in five people develops fever and feels unwell — are you still at risk to go on and have those complications?" he said.

"Those are really important, fundamental questions about the disease and the virus that need to be understood," Jackson said.

How can people with Zika be diagnosed quickly?

The possibility of links between Zika and neurological disorders leads to another puzzle piece: How do you know if you're infected?

"Eighty percent of people [infected with Zika virus] are asymptomatic," said Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. "Of the 20 percent with symptoms, the symptoms are usually mild — fever, rash, muscle aches, headaches, joint aches — nonspecific things. This is a significant challenge to all scientists," because it makes the infection hard to spot, Glatter told Live Science.

In other words, how can health officials contain a virus that usually lurks unseen?

Glatter recently co-authored a report in the Harvard Business Review recommending Zika-fighting strategies that were inspired by actions taken against the recent Ebola epidemic in West Africa. For Ebola, the use of rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) in the field allowed community health workers who lacked significant medical training to quickly identify infected people using a single drop of blood, Glatter explained. The RDT analyzed the blood, looking for an antigen, a protein produced by the actual virus itself, which would confirm the person was infected.

Developing, distributing and using such field kits in known Zika hotspots will be critical for containing infection, Glatter said. "The rapid diagnostics are really where it's at, in order to quell and reduce the spread of patients that are infected," he said.

"The pace is feverish right now, especially at the CDC, to develop one of these antigen-detection kits, because unless you get it into communities where the virus is active, you don't know who can stay and who can leave," Glatter said.

But there are properties of the Zika virus that present additional obstacles to developing these field tests, he said.

"The problem is that it's rapidly changing," Glatter told Live Science. "There are certain proteins on the capsule of the virus that have the ability to mutate, so getting the exact proteins that we're looking for in terms of the antigens that will be employed in a kit is really the crux of the issue, and really the challenge at this point," he said.

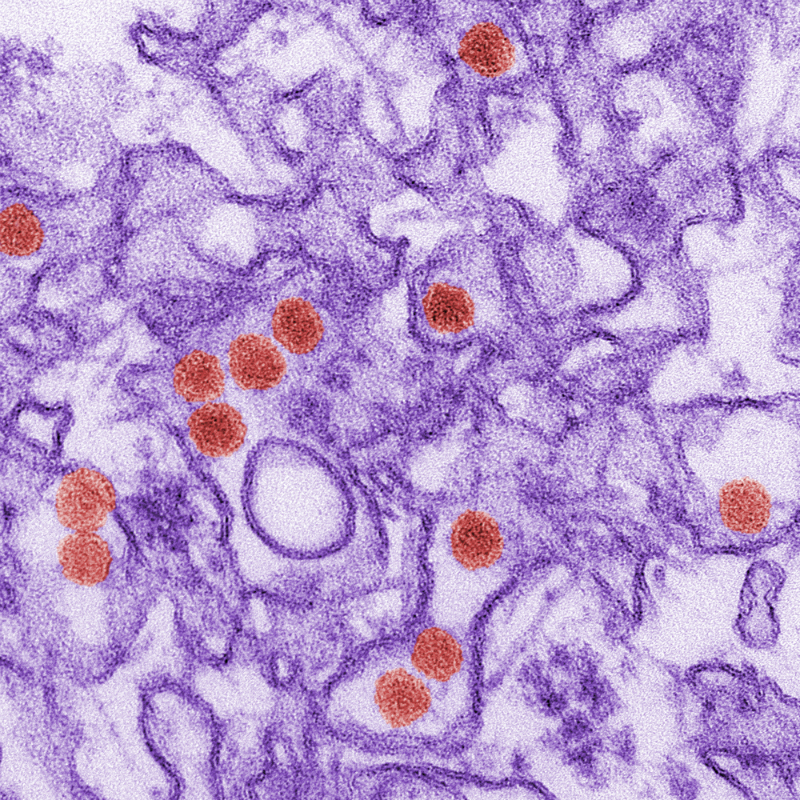

And Zika's similarity to other viruses in its family could also complicate the diagnostic process, said Alan Barrett, director of the Sealy Center for Vaccine Development in Texas. Zika is part of the flavivirus family, which means it's genetically similar to the viruses that cause dengue, yellow fever and West Nile infections.

"In Brazil, where they have 10 different [types of] flaviviruses, trying to identify Zika from dengue or a different virus is going to be very difficult," Barrett told Live Science.

How is Zika spreading?

Another mystery surrounding Zika is how exactly the virus has accomplished its recent, unprecedentedly rapid spread across the Americas, into areas where it had never been detected before. Researchers have long known that Zika is primarily carried by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, and this species is highly adaptable. Scientists also think that climate change has made some environments more hospitable to mosquitoes than they used to be. But there are other unknowns related to Zika's mosquito carriers.

"Is it using the same mosquito vectors across South America? The assumption is yes, but we haven't proved that definitively," Barrett told Live Science. "Is it a strictly human virus cycle, like chikungunya? If animals are involved as a reservoir, it's going to be much harder to get rid of it. Are humans dead-end hosts for Zika, or is there active enough replication for mosquitoes to spread it from human to human? There are lots of things we still don't understand," he said.

Glatter said humans are likely to blame as well for the rapid spread.By producing large quantities of garbage, people provide breeding grounds for the bloodsuckers that might be carrying viruses.

"We have an explosion of garbage throughout our world that's spurred the development of Aedes aegypti," Glatter told Live Science."It lives in tires. It's adapted to live in plastic. These are ideal habitats for mosquitoes to lay their eggs. All it needs is a little moisture, and they're good to go. Our problem with trash is a root cause for the rise of mosquitoes," Glatter said. [Sting, Bite & Destroy: Nature's 10 Biggest Pests]

How many people may be infected by other routes of Zika transmission?

Recent evidence suggests that the virus can sometimes spread through other paths.

Earlier this month, in Texas, a person was diagnosed with sexually transmitted Zika, the first case of locally acquired Zika infection in the United States this year. Previous instances of Zika spreading through semen were reported in Colorado in 2008 and in French Polynesia in 2015.

It's unclear how often sexual transmission may happen, and whether it's easy or difficult for the virus to spread this way. But the CDC recently issued a warning on its website for pregnant women who have male partners who traveled to or live in a Zika hotspot: Those women should either abstain from sex or use condoms for vaginal, anal and oral sex for the duration of the pregnancy, the warning said.

Transmission through blood transfusions is also possible, evidence has shown.

On Feb. 4, Brazil health officials confirmed two cases of Zika infection linked to blood transfusion, Reuters reported.

A bulletin issued Feb. 1 by the American Association of Blood Banks (AABB) in response to the Zika outbreaks recommends that travelers to Mexico, the Caribbean, or Central or South America self-defer from donating blood for at least 28 days after their return to the United States. According to the bulletin, "2.8 percent of blood donors tested positive for Zika RNA during the French Polynesian outbreak."

Following the AAAB's recommendation, the American Red Cross issued a statement on Feb. 2 that its representatives would implement self-deferral for prospective blood donors. The organization added it would request that if donors develop Zika symptoms within two weeks after donating, they contact the Red Cross immediately so that their blood donations can be quarantined.

How can future pandemics be prevented?

While scientists race to answer these and other questions about Zika in order to contain and defeat the virus, they are also looking ahead and anticipating the next pandemic, Glatter said.

"Zika is here to stay in the Americas. It's going to be a part of our lives for years to come," Glatter said. "We need to look at the time line and get a good idea of what the viruses are that are a threat to the human race, and invest in technologies and spot the trends early to become more proactive and less reactive."

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.