Archaeologists recently raised a nearly intact medieval shipwreck from the bed of a river in the Netherlands. The wooden ship, which was found at the bottom of the Ijssel River near Kampen, was at least 600 years old and was in rather pristine condition, with an intact brick oven and glazed tiles found in the galley. [Read the full story on the Medieval trading ship]

Medieval origin

The wooden, flat-bottomed ship was first discovered in 2012 while a national organization was carrying out investigations to preserve water safety in the Dutch river. The ship was found along with a river barge and a punt, a vessel used especially for navigating river deltas. All three boats were submerged in the Ijssel River, in the Netherlands. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

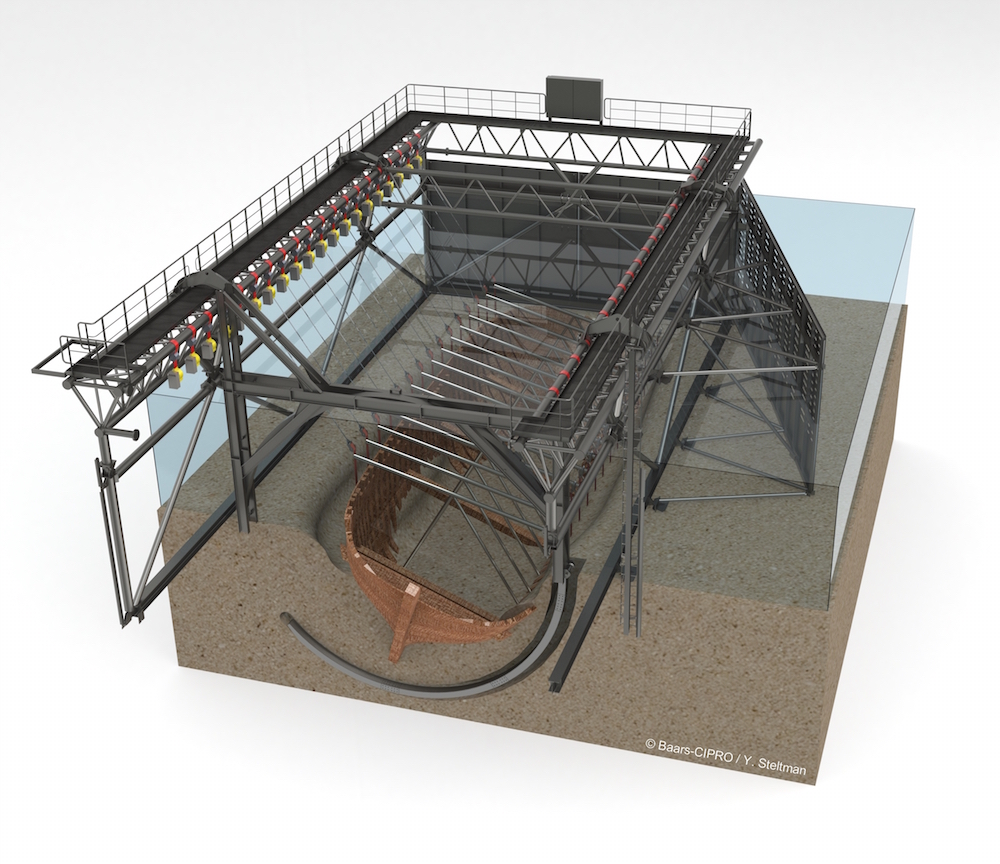

Herculean effort

Getting the massive ship out of the river intact proved to be an extremely involved project. A huge platform was built around the shipwreck (shown here in 3D reconstruction). (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Characteristic cog

The ship had characteristic construction found in a medieval ship called a cog. Those features included the length-to-width ratio, the steep, straight prow and stern and deck beams that jut out through the outer skin of the ship. The large ship (shown here in 3D reconstruction) had been submerged in the frigid waters for at least 600 years. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stunningly preserved

The cog was stunningly preserved; some of the caulking used to seal the ship, and many of the nails, were still found in place. Because the boat was held together with metal support structures, such as nails, it didn't collapse into a pile of wood, as the barge did when it was lifted from the water. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Deliberately sunk?

While archaeologists don't know for sure how the Ijssel cog wound up at the bottom of the river, one likely possibility is that it was deliberately sunk, along with the two other vessels. During the 1500s, the river was filling with silt, which was creating large sandbanks that prevented ships from making port. To counteract that problem, medieval maritime engineers may have attempted to dam the river or divert its flow slightly away from those sandbanks. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Large ship

The cog itself was nearly 65 feet (20 meters) by 26 feet (8 m) wide and weighed a whopping 55 tons (50 tonnes). The boat had been stripped of much of its original glory, but the team did find anchors and dredges, as well as a stay support, a metal structure designed to hold the ropes that support the ship's mast. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

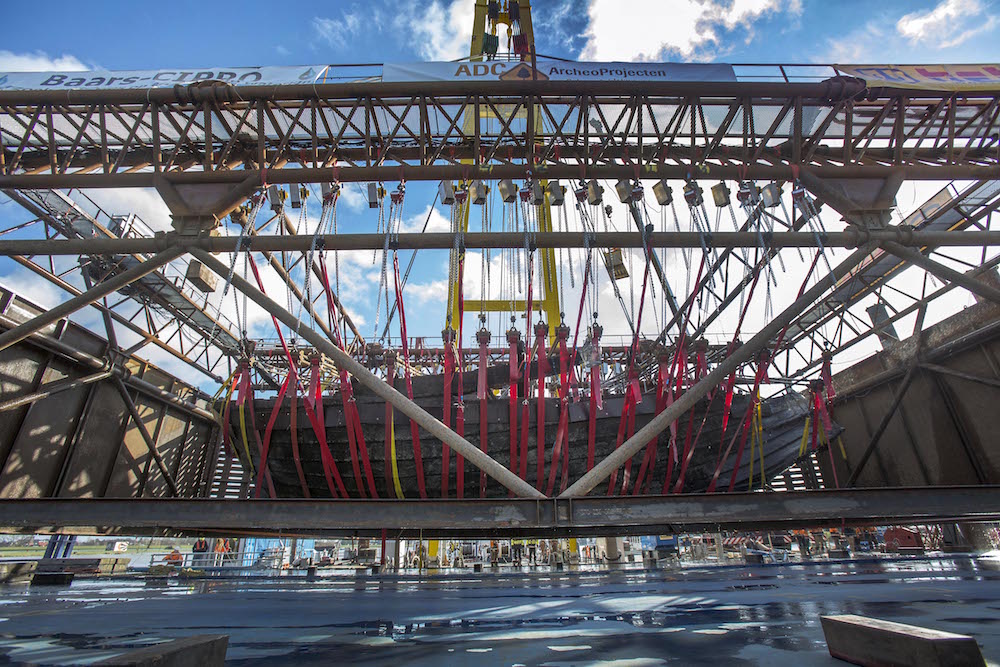

Careful extraction

The effort to extract the ship was monumental. It involved suctioning out the site underwater, bracing the ship bottom with a kind of basket made of straps, then carefully inching the boat out of the water on a crane. Each of the straps has its own computer guiding its motion, which allowed the excavation team to have fine-grained control over the boat's removal. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Stunning details

While archaeologists originally though the boat was completely dismantled before being sunk, it turned out the cog still harbored its ancient galley, complete with a glazed tile deck and a brick oven. The bricks, a traditional Dutch type known as "klostermoppen," date to the 13th century. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Preserving the boat

Now that the boat is outside the water, researchers have placed it on a pontoon, where it will be encased in a protective frame. From there, the boat will be moved to Batavialand in Lelystad, the Netherlands. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Keeping cool

To protect the ship from damage, the team has created both wet and dry stations nearby at the Nieuw Land Heritage Centre. The climate-control system will keep the boat wet all the time. Here, a worker wets some of the wreckage found from the site. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Public viewing

If the boat is in good enough condition, the team hopes to eventually dry out the boat for display in a museum, a process that could take three years. However, if the boat is too fragile to be dried out, it will be thoroughly studied and mined for its medieval secrets, then destroyed. (Photo credit: Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands)

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus