Swim Like a Butterfly? Sea Snail 'Flies' Through Water

Some ocean-dwelling creatures ended up with common names that seem to belong to another animal entirely: A sea cow has neither horns nor an udder. A sea lion lacks a tawny mane. And jellyfish aren't true fish at all.

But the sea butterfly, a tiny marine snail, has more in common with flying insects than you might expect, according to a new study.

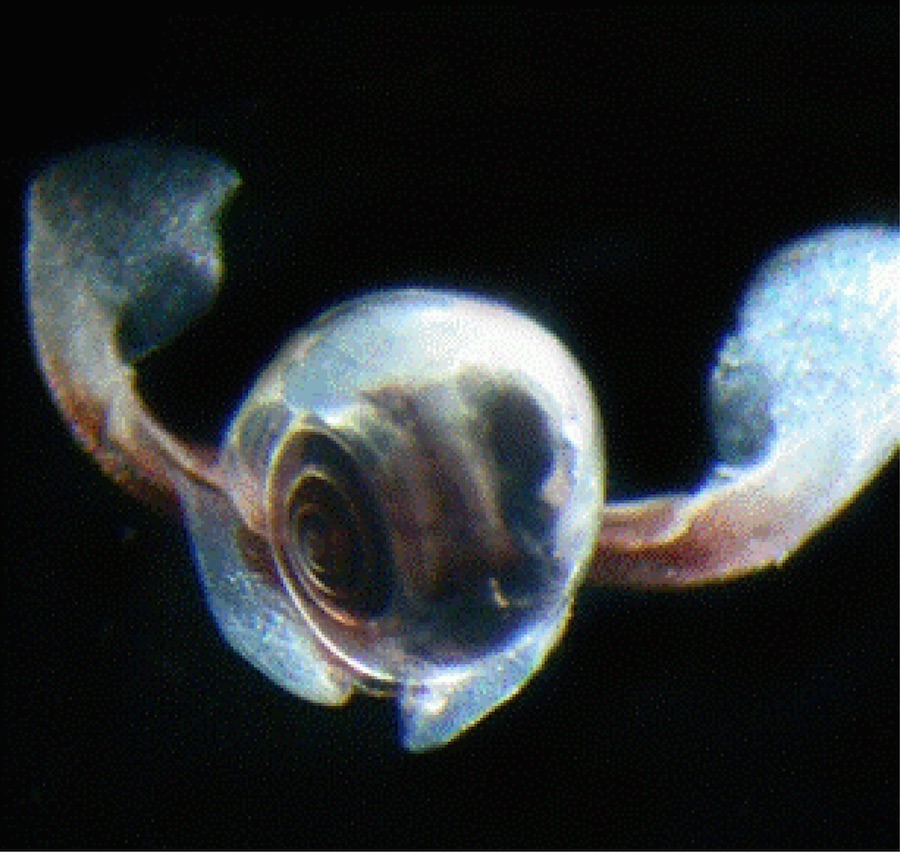

Also known as Limacina helicina, the sea butterfly navigates cold ocean waters in the northern Atlantic and Pacific. Its shell measures about 1 to 4 millimeters (0.04 to 0.16 inches) in diameter, and it swims using a pair of winglike appendages. It can retract these into its shell when threatened.

Many types of zooplankton, tiny ocean animals, have structures like the sea butterfly's, which they use as paddles to propel themselves through the water. But when researchers conducted the first-ever analysis of how the sea butterfly's appendages move, the scientists found that the creature swam in a completely unexpected way. It used movements entirely unlike the paddling of other zooplankton. [Video: Watch the Sea Snail Fly Like a Butterfly through Water]

An honorary insect

"The more we looked into it, the more we found that the sea butterfly is an honorary insect," said study co-author David Murphy, from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

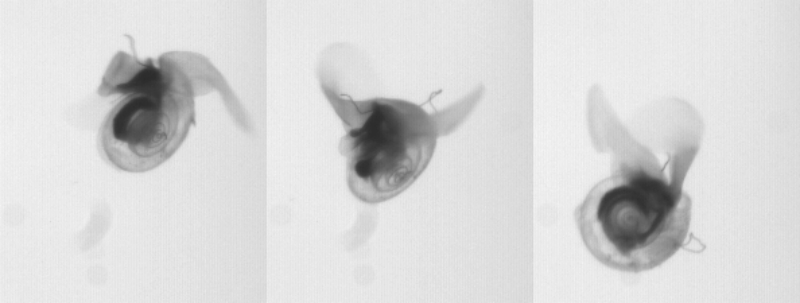

"We looked at the wing kinematics — how it moves its wings in a figure-eight pattern —and it's very similar to how a fruit fly beats its wings," Murphy told Live Science in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To capture these hard-to-see movements, Murphy explained, the scientists used four high-speed cameras that recorded the snails as they swam in an aquarium, within a zone lit up by infrared lasers. But the researchers also wanted to track the movement of the water as the sea butterflies displaced it. To do that, the scientists seeded the water with tiny, light-reflecting particles.

"The four cameras let us determine the 3D position of each of the thousands of these particles," Murphy said, "and from their movement, we can measure the 3D flow around the animal."

"Clap and fling"

The researchers found that the sea butterfly was using a flying trick common to many small insects: a technique called "clap and fling," in which the animal claps its wings behind it and then flings them apart, Murphy explained. This creates a miniature vortex of airflow — or water flow, in the sea butterfly's case — at each wing tip, providing extra lift.

Measuring the wing motion and water flow wasn't easy, Murphy said. The setup, calibration and alignment of the image-capture system took an entire day, Murphy told Live Science. To make the trials even more challenging, the subjects weren't exactly what you'd call robust, he said.

"Sea butterflies are extremely fragile. They're sort of gelatinous like jellyfish, except for the hard shell," Murphy said. This presented challenges for shipping the creatures successfully from the West Coast, and for keeping them in good condition. But luck was with the researchers, and their wee swimmers not only arrived safely, but were also extremely cooperative, he said.

"It's really hard to get the animals to swim right in front of the camera, but these behaved beautifully and gave us perfect data," Murphy said.

The findings were published online today (Feb. 17) in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.

'A relationship that could horrify Darwin': Mindy Weisberger on the skin-crawling reality of insect zombification

'Dispiriting and exasperating': The world's super rich are buying up T. rex fossils and it's hampering research

Trove of dinosaur footprints reveal Jurassic secrets on Isle of Skye where would-be Scottish king Bonnie Prince Charlie escaped