Spiders Look Bigger If You’re Afraid of Them

People who fear spiders tend to perceive these creepy-crawlies as larger than they actually are, a new study finds.

The research, though hair-raising for some, could be useful in treating phobias, the scientists said.

"We found that although individuals with both high and low arachnophobia rated spiders as highly unpleasant, only the highly fearful participants overestimated the spider size," Tali Leibovich, a researcher in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at Ben-Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev in Israel, said in a statement.

The idea for the study came from a real-life experience, the researchers said. One day, Noga Cohen, a graduate student of clinical-neuropsychology at BGU, noticed a spider crawling along. Leibovich, who has arachnophobia, asked Cohen to get rid of the "big" spider. [Creepy, Crawly & Incredible: Photos of Spiders]

Cohen thought the request strange, especially because she thought the spider looked small, she said in the statement.

"How could this be if we both saw the same spider?" Cohen asked.

So, the researchers devised an experiment to figure out whether arachnophobia influences people's perceptions of spiders. The scientists included only women in the test, "due to the higher probability of women to suffer from spider-phobia compared to men," the researchers wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In one experiment, the scientists gave 80 female students a questionnaire to rate their levels of arachnophobia. The researchers took only the top 20 percent and bottom 20 percent of respondents, or 12 students who said they were very afraid of spiders and 13 who said they were unafraid of the eight-legged arthropods.

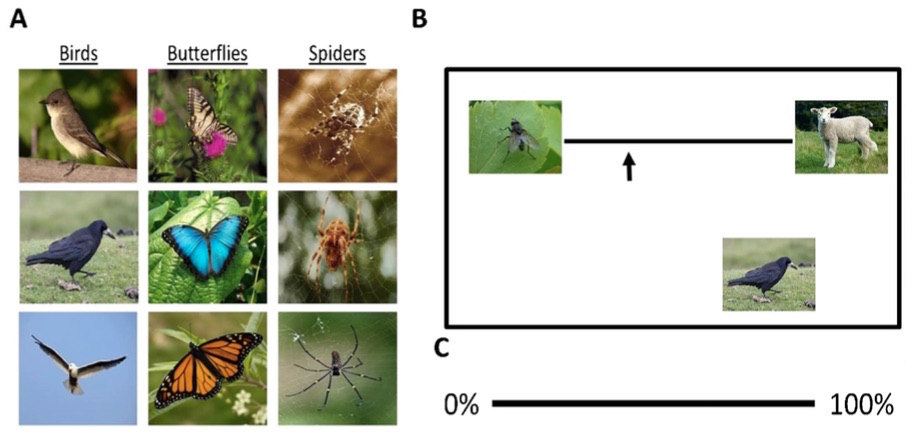

The scientists then had the students sit at a computer that showed a sliding scale, with a photo of a fly at one end and a photo of a lamb at the other. A computer program then presented the students with several photos of birds, butterflies and spiders, and asked the participants to click where on the sliding scale each animal fit in terms of size. The program also asked each participant to rate whether they found each photo pleasant or unpleasant.

Overall, every student found pictures of spiders unpleasant. However, only students in the fearful group overestimated the size of the spiders compared with the butterflies, according to the study.

The researchers said they wondered whether this effect was unique for spiders, or whether it held for other feared critters. So, the scientists did a second experiment, asking 64 female students to do the same program, but this time with photos of wasps, beetles and butterflies joining the spider pictures.

The group with a high fear of spiders rated the wasps as more unpleasant than did the low-fear group, but (surprisingly) the highly fearful group didn't overestimate the size of the wasps.

"These results may suggest that unpleasantness by itself cannot account for bias in size estimation," the researchers wrote in the study. What's more, it shows that emotion can influence how people perceive the size of spiders, they said.

"This study also raises more questions such as: Is it fear that triggers size disturbance, or maybe the size disturbance is what causes fear in the first place?" Leibovich said. "Future studies that attempt to answer such questions can be used as a basis for developing treatments for different phobias."

The study was published online Jan. 21 in the journal Biological Psychology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.