Palm-Size Satellites Could Hunt for New Alien Worlds

Tiny satellites could hitch a ride into orbit and spot alien worlds from afar, new research suggests.

NASA's 2,230 pound (1,052 kilogram) Kepler Space Telescope has discovered thousands of potential planets around other stars. Now, some scientists want to go smaller: They propose searching for new worlds using miniaturized satellites that can fit in the palm of your hand.

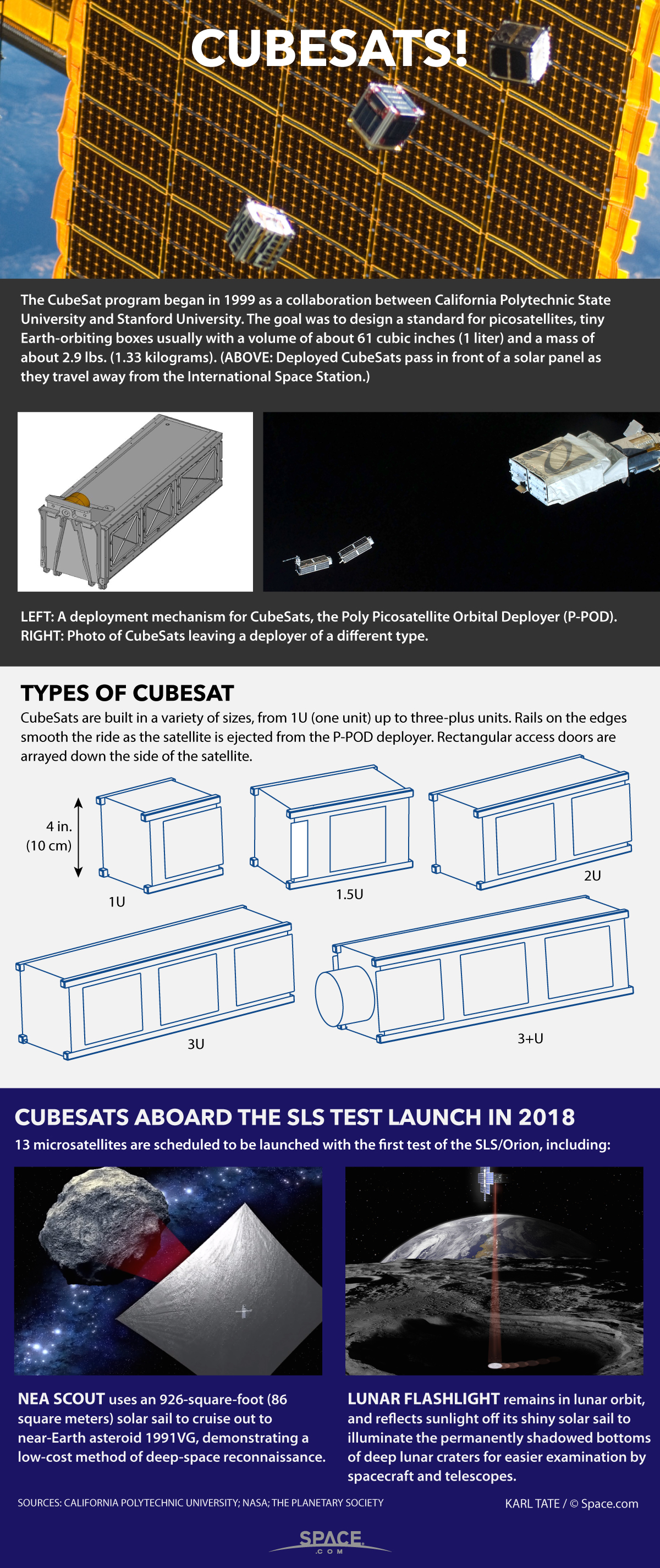

"We want to be cheaper than sending up a huge satellite, to be able to collect more data in less time for less money," Ameer Blake, an undergraduate student at Howard University in Washington, D.C., told Space.com. Blake and his adviser, Aki Roberge, a research astrophysicist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, studied the possibility of using a smaller instrument known as a cubesat to search for a new planet around the star Beta Pictoris, already known to host at least one world, Beta Pictoris b. He presented the results in January at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Kissimmee, Florida. [CubeSats: Tiny, Versatile Spacecraft Explained (Infographic)]

"We wanted to know, are there any other planets other than Beta Pictoris b, and if so, where are they?" Blake said.

Small but powerful

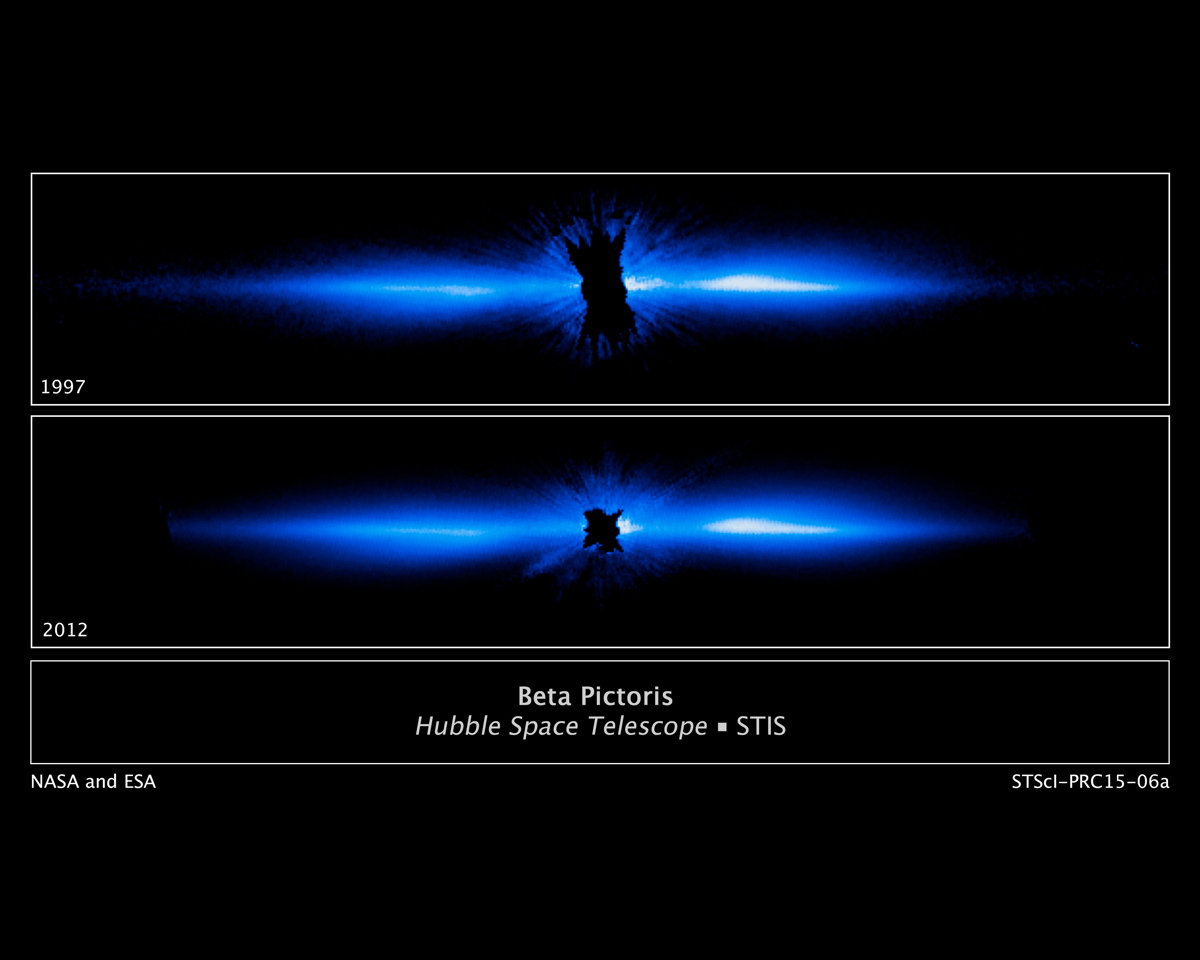

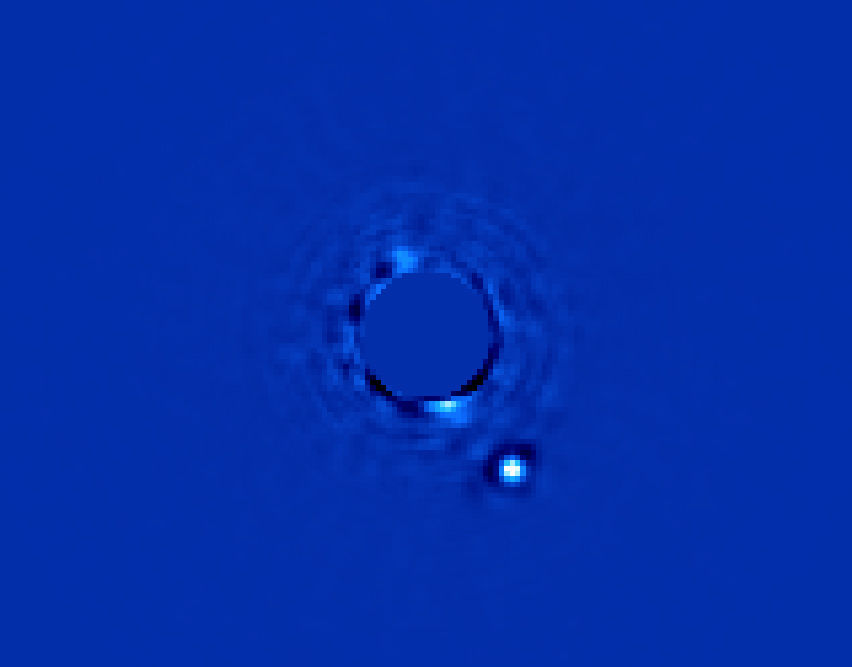

In 2008, scientists used NASA's Hubble Space Telescope to reveal a giant planet more than 1.5 times the radius of Jupiter orbiting Beta Pictoris. Circling only nine times the Earth-sun distance from its star, just inside what would be the orbit of Saturn in the solar system, Beta Pictoris b is the closest orbiting exoplanet captured by direct imaging, the technique that essentially photographs other worlds. The method is most sensitive to giant planets several times the mass of Jupiter, and faces challenges when it comes to spotting smaller worlds or worlds close to their star.

Blake and Roberge are interested in launching a cubesat into space to search for a new world around the star. The evidence suggests the star's system sits nearly edge-on as seen from Earth — that is, oriented so we're looking at the edge of the system rather than from above or below. Researchers have seen a debris disk that stretches to over 1,400 times the Earth-sun distance on both sides of the star, and the known planet's orbit also agrees with that orientation. This should allow a cubesat to search for other planets using a process called the transit method, which should be able to see worlds inside the orbit of Beta Pictoris b.

Unlike direct imaging, which relies on capturing the light reflected from a planet, the transit method, which is also used by the Kepler telescope, searches for dips in the brightness of the star as a planet moves between it and Earth. Instruments can only detect the transiting planets' presence if they pass between the star and Earth, so the system must lie within a few degrees of being edge-on to Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on their preliminary study, Blake said that a cubesat should be able to spot the most massive gas giants on a short orbit.

"We would definitely be able to see hot Jupiters," he said, referring to the worlds several times the mass of the solar system's largest planet in orbits closer than Mercury's.

"We would like to get as small as maybe Neptune-size planets, but things get more complicated when you get to smaller sizes."

Stare & collect

Several years ago, planet hunter Sara Seager, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, proposed using a fleet of cubesats to survey part of the sky in search of worlds beyond the solar system. Blake said the idea inspired him and his adviser to consider a single instrument targeting only one star. This avoids concerns about focusing or redirecting a suite of satellites.

"This is just, stare at one thing and collect as much information as possible," Blake said.

Blake said that sending up a single satellite would make a good first step toward an entire fleet. Once the method is proven to work, other satellites could be launched to either discover new worlds or confirm preliminary observations, such as those made by Kepler.

When it comes to discovery, however, the search would need to be limited to stars which already demonstrate that their systems are edge-on to Earth. Researchers can identify such stars by observing massive debris disks around them or targeting stars with directly imaged worlds whose orbits are edge-on.

Cubesats were first introduced in 1999 as compact satellites that university students could construct to perform experiments and test new technologies. They take the standardized shape of a 4 x 4 x 4-inch (10 x 10 x 10 centimeters) cube, which allows them to hitch a ride into space with other, larger launches. Two will be launched in March 2016 to cover the entry, descent, and landing of NASA's upcoming Mars InSight lander, while other scientists have discussed dropping them off at destinations such as Europa and Enceladus. [CubeSats Are Bound For The Planets (Video)]

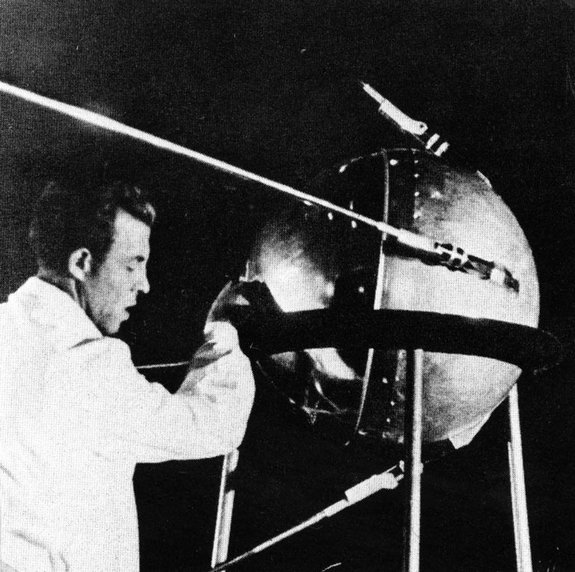

The space age dawned with the launch of Sputnik 1, Earth's first artificial satellite, in 1957. Thousands of additional spacecraft have followed in Sputnik's footsteps, serving humanity in a variety of ways. How well do you know Earth's satellites?

Satellite Quiz: How Well Do You Know What's Orbiting Earth?

The biggest challenge for a cubesat mission to hunt for worlds around a specific target has to do with time. The scientific community requires at least three transits — three times an object must pass between its sun and the Earth — to confirm its status as a planet. Blake's study suggests a maximum of a year and a half for a cubesat orbit, though it may last for only half a year. To confirm a planet would require finding those which circle their stars every two to six months.

Blake and Roberge have performed the background study that shows using a cubesat to search for worlds around Beta Pictoris is a viable plan. Their next step is to speak to engineers and instrumentalists to determine what parts would be necessary to construct such a satellite. From there, they can make estimates on what building it might cost — though it should come in far less than Kepler's $550 million price tag.

"I think it would be great to be able to find exoplanets with less material and preferably in quicker time," Blake said.

"It would be just a little better for everybody."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children.