Zika Virus Linked to Stillbirth

A woman in Brazil who became infected with the Zika virus gave birth to a stillborn baby, and large parts of the infant's brain were missing, according to a new report.

Moreover, the fetus had damage to tissues outside of the central nervous system, the researchers said. For example, the infant's body had an abnormal accumulation of fluids.

"These finding raise concerns that the virus may cause severe damage to fetuses leading to stillbirths, and may be associated with effects other than those seen in the central nervous system," study author Dr. Albert Ko, chair of the Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases at the Yale School of Public Health, said in a statement.

However, this was an isolated case, and more research is needed to determine whether Zika virus can actually cause some of the health effects seen in the fetus, he said.

And because this was a single case, it is not possible to estimate the risk of stillbirth among women who are exposed to the Zika virus during pregnancy, the researchers said.

The 20-year-old woman described in the report had a normal pregnancy during the first three months. However, at around her 18th week of pregnancy, an ultrasound showed that the fetus weighed much less than normally developing fetuses weigh at that point. [Zika Virus Special Report: Complete Coverage of the Outbreak]

The woman did not have any of the common symptoms of Zika virus infection, such as rash, fever or body aches, either shortly before she got pregnant or while she was pregnant.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By the 30th week of the woman's pregnancy, the doctors knew the fetus would have several congenital conditions, the report said. For example, the fetus's head was abnormally small, and parts of the brain were missing.

An ultrasound in the 32nd week of pregnancy showed the fetus had died, and the doctors induced labor shortly after. Then, the researchers confirmed the presence of Zika virus in the fetus. It also turned out the fetus had joint deformities.

Some other mosquito-borne viruses can affect the brain of a person who is bitten. For example, some people with West Nile virus infections can develop a severe form of the disease called West Nile encephalitis.

But no other mosquito-borne virus has been linked to neurological effects in a fetus carried by a woman who was bitten, said Dr. Richard Temes, director at the Center for Neurocritical Care at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, New York, who was not involved in the report.

"This is really the first virus that is not causing neurological damage to the host, or the person the mosquito bites, but it is actually transmitted to the fetus that the host is carrying," Temes told Live Science.

Researchers don't know the potential mechanism behind the link between this neurological damage and the Zika virus, he said. However, it appears that the fetal brain may be particularly susceptible to damage from the virus in the first trimester of pregnancy, as this is when the most rapid brain development occurs, he added.

Doctors recommend that women in any stage of pregnancy avoid traveling to places affected by the Zika outbreak, such as Brazil, Temes said.

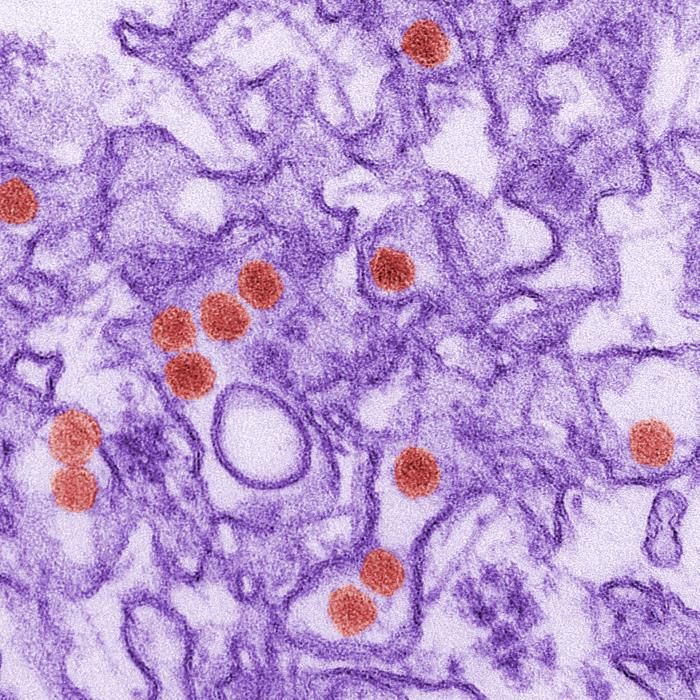

Most people who become infected with the Zika virus show no symptoms of the infection, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Researchers are concerned about the virus primarily over a possible link between Zika infections in pregnant women and a congenital condition called microcephaly in their infants. Babies with this condition are born with underdeveloped brains, and face severe, lifelong cognitive impairments. However, the link between the condition and the virus is not proven, and studies are underway to look at the link more closely.

The new report was published today (Feb. 25) in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Follow Agata Blaszczak-Boxe on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular