T. Rex Was Likely an Invasive Species

Tyrannosaurus rex, king of the dinosaur age, wasn't a North American native as many experts had previously thought, a new study suggests.

Instead, the giant tyrannosaur was likely an invasive species from Asia that dispersed into western North America once the opportunity presented itself, paleontologists said.

"It's possible that T. rex was an immigrant species from Asia," said study co-researcher Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. But he cautioned that the finding isn't necessarily a "slam dunk," and that more research is needed to say for sure. [Gory Guts: See Photos of a T. Rex Autopsy]

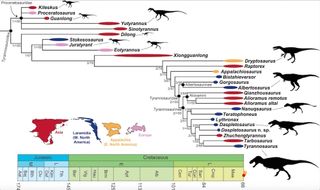

T. rex is one of the biggest meat eaters ever to live on land, but relatively little is known about its family tree. In a study published earlier this month, Brusatte and Thomas Carr, an associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin, analyzed 28 different tyrannosaur species and constructed a family tree, noting approximately when and where each species lived.

Fossil evidence is lacking, but researchers suspect that the predecessors of tyrannosaurs lived on the supercontinent Pangaea, which began to break up about 200 million years ago, during the Triassic period. This would explain why tyrannosaurs fossils have been found on different continents, including Asia, western North America (called Laramidia at the time), eastern North America (Appalachia) and Europe, Carr said.

As time went on, the tyrannosaurs evolved in their respective places, meaning that the tyrannosaurs in Asia grew to look different than the ones in North America. But, around 67 million years ago, the seaway between Asia and North America went down, leaving a land bridge between the two continents, Carr said.

Perhaps T. rex crossed this route into North America, Carr said. Researchers have uncovered countless T. rex fossils in western North America, but a careful analysis of T. rex's skeletal features suggests that it is Asian in origin, the paleontologists found.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, T. rex is closely related to two Asian tyrannosaurs, Tarbosaurus and Zhuchengtyrannus, the researchers found.

"Tarbosaurus is the Asian version of T. rex," Brusatte told Live Science in an email. "Or, you could say that T. rex is the North American version of Tarbosaurus. They are so similar in terms of their monstrous size, their proportions, their massive jaw muscles and thick teeth and even many minutiae of their skull bones."

Zhuchengtyrannus is also similar to T. rex, though it's more distantly related, Brusatte and Carr said.

Asian invasion

T. rex lived from about 67 million to 65 million years ago, going extinct when a 6-mile-long (10 kilometers) asteroid slammed into Earth and killed the nonavian dinosaurs.

During that time, the 7-ton (6.3 metric tons) T. rex monster spread from modern-day Alberta to Texas. (A giant seaway in the middle of North America prevented T. rex from reaching the East Coast, the researchers said.) Before T. rex invaded North America, presumably from Asia, other tyrannosaurs lived in western North America, but they disappeared shortly after T. rex came onto the scene.

It's unclear why these large tyrannosaurs went extinct, but T. rex may have played a role in their demise, the researchers said. [Photos: The Near-Complete Wankel T. Rex ]

"Regardless of where T. rex comes from, when it enters the fossil record, it seems to take over immediately, like an invasive species," Brusette said. "It rose to the top of the food chain and elbowed out all competitors — or perhaps I should say outmuscled them, as their pathetic little arms didn't have very big elbows."

The new finding contradicts earlier studies, some of which say that T. rex is the culmination of tens of millions of years of dinosaur evolution within North America, Brusatte said.

"This also is a good example of how different family trees can imply different things about evolution," Brusatte said. "This is why we spend so much time building family trees for fossil groups: They tell us how different species are related to each other, which then allows us to tease out their evolutionary stories, the same way constructing genealogies for our own families tells us how our ancestors led to us."

The study was published online Feb. 2 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.