Oldest Muslim Graves in France Discovered

Three medieval graves in southern France may hold the remains of three Muslim men, a new study finds.

Several clues provide hints about the graves' occupants. Not only are the individuals' faces oriented toward Mecca, a holy city for Muslims, but the shape of the grave is reminiscent of other Muslim burials, the researchers said.

If the individuals were indeed Muslim, these graves would be the earliest Muslim burials on record in France, the researchers said. [Images of a Medieval Mass Burial in Paris]

"It's a new insight on the knowledge of settlement of French territory," said study co-lead researcher Yves Gleize, an archaeologist and anthropologist at the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research and the University of Bordeaux. "I hope that, in the future, we'll find other Muslim burials to [help pinpoint] the Muslim occupation in the south of France."

Gleize and his colleagues found the graveyard during an excavation of a Roman quarter in Nimes, in southern France. (The excavation took place before a parking lot was built over the area, Gleize said.) As time went on, they found about 20 scattered graves; the lack of any order suggested that these bodies weren't buried in a cemetery, he said.

"We knew that during the early Middle Ages in France, there were a lot of scattered graves in [the] countryside," Gleize told Live Science in an email. "But I was very surprised when I looked at the position of the skeleton in three of these graves."

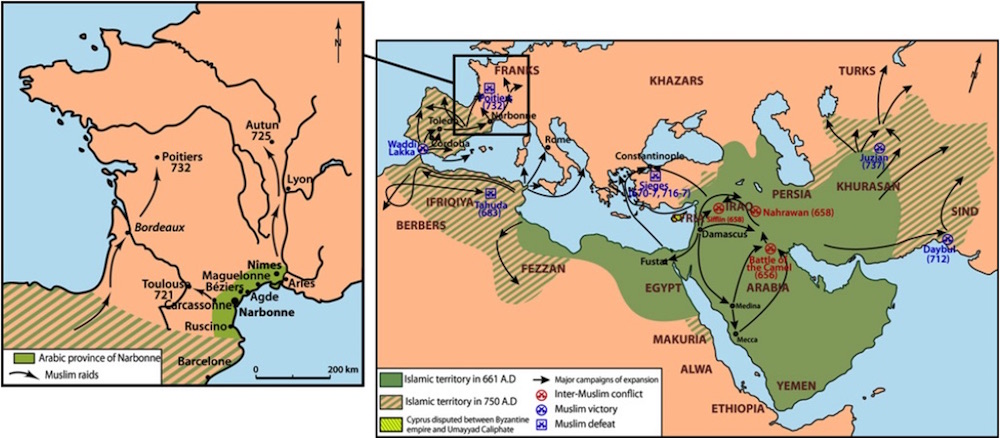

During the Middle Ages, the Arab-Islamic conquest led to significant political and cultural changes around the Mediterranean. There is evidence that Muslims lived on the Iberian Peninsula during early medieval times, but there is less evidence of them north of the Pyrenees, the mountain range that separates Spain from the rest of mainland Europe, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Gleize knew of Muslim graves at Montpellier and Marseille dating to the 12th and 13th centuries, respectively. But radiocarbon dating showed that the newfound graves are even older, dating to between the seventh and ninth centuries, he said.

Historical records indicate that there was a Muslim presence in France during the early Middle Ages, during the eighth century, so the dates for these graves make sense, he said.

Grave research

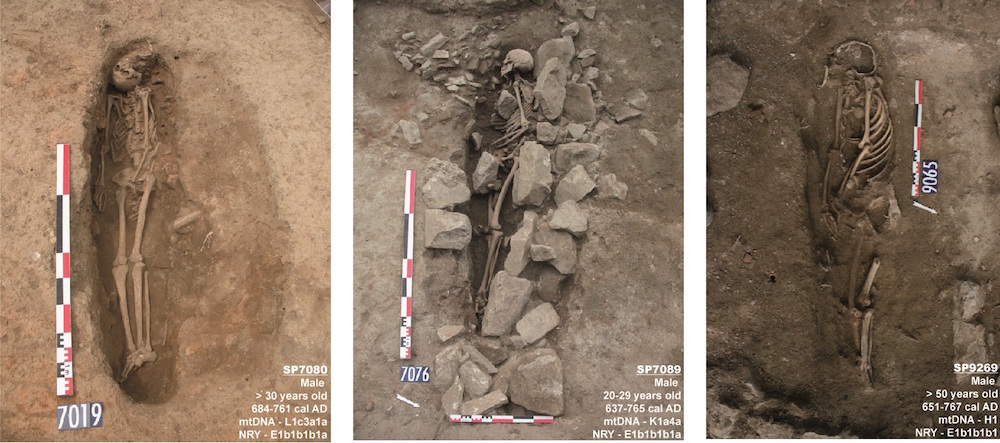

After discovering the graves, Gleize and his colleagues studied the funerary practices, analyzed the individuals' DNA and determined their sex and approximate ages.

The analyses indicated that the men — adults ranging from about 30 to older than 50 years old — were Muslim, Gleize said. The bodies (buried on their right sides) and faces (which are oriented southeast) point toward Mecca. Moreover, the burial pits are socket-shaped, a design feature common among Muslim graves, he said.

An analysis of the DNA and mitochondrial DNA (genetic material passed down through the maternal line) showed that these men likely descended from, or were related to, people who lived in North Africa. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

These clues suggest that the three men were Berbers, a group of North Africans who integrated with the Arab religion and armies during the early Middle Ages. It's likely these men were part of the Umayyad army, the force that conquered southwest Europe beginning in the eighth century, the researchers said.

"For the moment, we cannot assert that they were born in North Africa, but their presence in [the] south of France is surely linked with the presence of Berbers in the Arab army," Gleize said.

Though the graves suggest that Muslims lived in southern France during the Middle Ages, Gleize said he and his colleagues "don't know about the type of contact [they had] with the local population," he said. "[But] one of the skeletons was surely more than 50 years old," he added. "It's possible that he lived several years at Nimes before he died."

The findings were detailed online Feb. 24 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.