Nonhuman 'Hands' Found in Prehistoric Rock Art

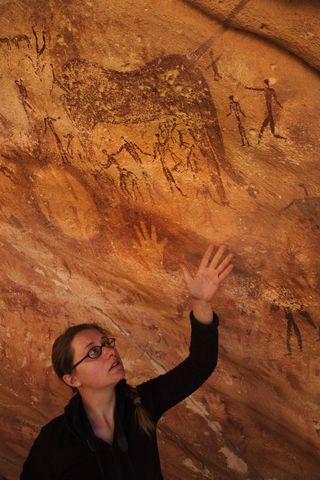

The roughly 8,000-year-old "hands" painted on a rock wall in the Sahara Desert aren't human at all, as researchers originally thought, but are actually stencils of the "hands" or forefeet, of the desert monitor lizard, a new study finds.

These tiny lizard hands are intermingled with paintings of human adult hands, which ancient rock artists stenciled around using red, yellow, orange and brown pigments, the researchers said.

It's unclear why these ancient people used both human and lizard hands as stencils, but the finding may provide clues about the mysterious people who lived in the Sahara about 8,000 years ago, the researchers said. [Gallery: See Amazing Images of Cave Art]

"It completely changes the way we think about prehistoric people," said lead study researcher Emmanuelle Honoré, a research fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. "We never imagined they had such complex practices in that area at that time."

Researchers discovered the cave, called Wadi Sūra II, in the Egyptian part of the Libyan Desert in 2002. The cave is located about 6 miles (10 kilometers) from the renowned Cave of Swimmers (officially known as Wadi Sūra I), a site discovered in 1933 and made famous by the popular 1992 novel "The English Patient."

The Wadi Sūra II cave, which can also be described as a shelter because it's more of a rocky overhang, is about 66 feet (20 meters) long and 26 feet (8 m) deep. Roughly 900 stencil paintings of arms, feet, discs, sticks and tiny and large hands cover the rock walls inside the cave.

Honoré was stunned the first time she walked into Wadi Sūra II in 2006. "I immediately saw those tiny hands among [nearly] thousands of paintings," she said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In earlier studies, researchers hypothesized that the large and small hand paintings were stenciled around adult and baby hands. Yet, shortly after looking at the 13 "baby" hand drawings, Honoré concluded that they weren't human.

For one thing, they were too small to belong to a human infant, she said. Moreover, the digits were pointy and "very long and very thin," Honoré said. In contrast, human babies have fingers that are roughly the same length as their palms.

"After a few years, I was obsessed by this idea [that they weren't human]," Honoré told Live Science. "It came back to my mind every day, and I decided I had to test it."

Handy experiment

Initially, Honoré compared the hands of her newborn niece and cousins to the rock art. A simple comparison showed that the ancient prints were too small to be human, but she needed a larger sample of hands to say for sure. [Photos: 'Winged Monster' Rock Art in Black Dragon Canyon]

So Honoré worked with the Lille University Hospital in northern France, and ended up getting the hand measurements of 25 preterm babies and 36 typical babies who survived birth.

"We were really surprised; all of the parents agreed to [let their babies] take part in the experiment," Honoré said. "They were very enthusiastic that their babies could contribute to a scientific study."

Honoré and her colleagues also measured 11 of the tiny hands at the Wadi Sūra II site. (The other two were incomplete and difficult to measure, she said.) In addition, they measured 30 of the large hands at Wadi Sūra II and 30 hands from living adults, and found that they matched well, she said.

But several parameters indicated that the tiny hands were not human. Though the stenciled fingers were long, overall the hands were small — just 1.8 inches (4.5 centimeters) from the base of the palm to the end of the middle finger. That's much smaller than a human baby hand, which measures an average of 2.4 inches (6.2 cm) long, she said

"We were completely shocked by our own research because it brought up the question — if it's not babies, what is it?" Honoré said.

Hand detective

At first, Honoré thought the tiny hands belonged to a small monkey. But none of the thousands of monkey hand pictures she researched looked like those on the wall at Wadi Sūra II. Then, when she was doing research at a crocodile farm in Zambia, she realized that the prints belonged to a reptile.

The front feet of the desert monitor lizard (Varanus) had the closest match to the wall paintings, she found. A baby crocodile (Crocodylus) was another possibility. However, crocodiles likely didn't live in the desert at that time, so a person would have needed to transport one over from the Nile or another watery region, Honoré said.

Other prehistoric cultures used animals as stencils for their rock art. For example, the Aboriginal people used emu foot stencils in the Carnarvon Gorge and Tent Shelter in Australia, and choike/nandu (birds in the genus Rhea) stencils are in the rock art at La Cueva de las Manos in Argentina, the researchers wrote in the study.

It's unclear why the ancient people at Wadi Sūra II used reptile hands as stencils, but Honoré said she's working on a new study that analyzes possible reasons. [History's 10 Most Overlooked Mysteries]

"I think we have to remain a bit prudent," she said. "We have to explore all of the hypotheses without taking anything for granted."

Ancient art made from hand stencils is not too prevalent in the Sahara. This makes the new study an important one, said French rock expert Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, who was the first to hypothesize that the tiny hands were stencils of human baby hands, but was not involved in the new research.

"I am delighted to see that the statistic[al] analysis by the authors clearly demonstrates that these tiny hands are not human," Le Quellec told Live Science in an email. "I must say that I suspected that they were reptile hands, but I didn't publish that idea in our book on Wadi Sura, because my co-authors were considering it as fantasy assumption."

The findings are published in the April 2016 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.