In Photos: Amber Preserves Cretaceous Lizards

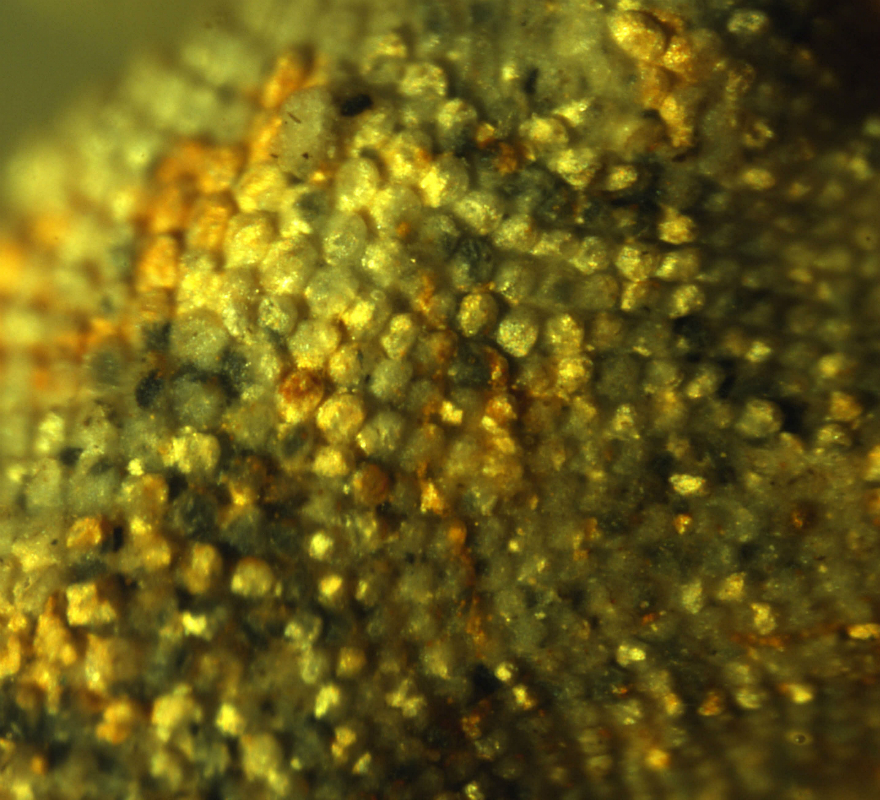

Colorful scales

Amber preserves ancient animals with a level of detail unrivaled by specimens fossilized in rock. By scrutinizing a group of lizards trapped in amber 99 million years ago, scientists discovered a number of unusual features that helped them identify the lizards' positions on their family tree. This image shows the scales on a preserved hind leg with scale pigmentation still visible, at 7X magnification.

[Read the full story on the amber-imprisoned lizards]

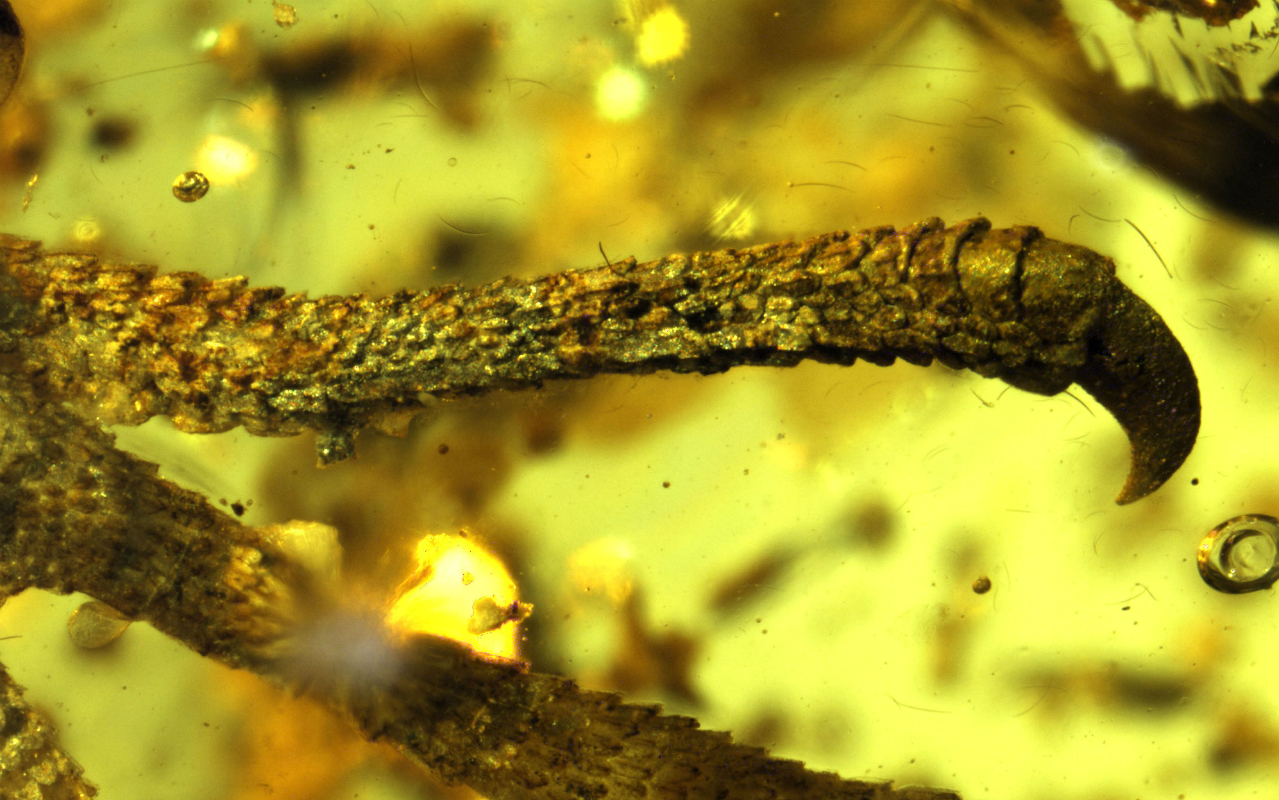

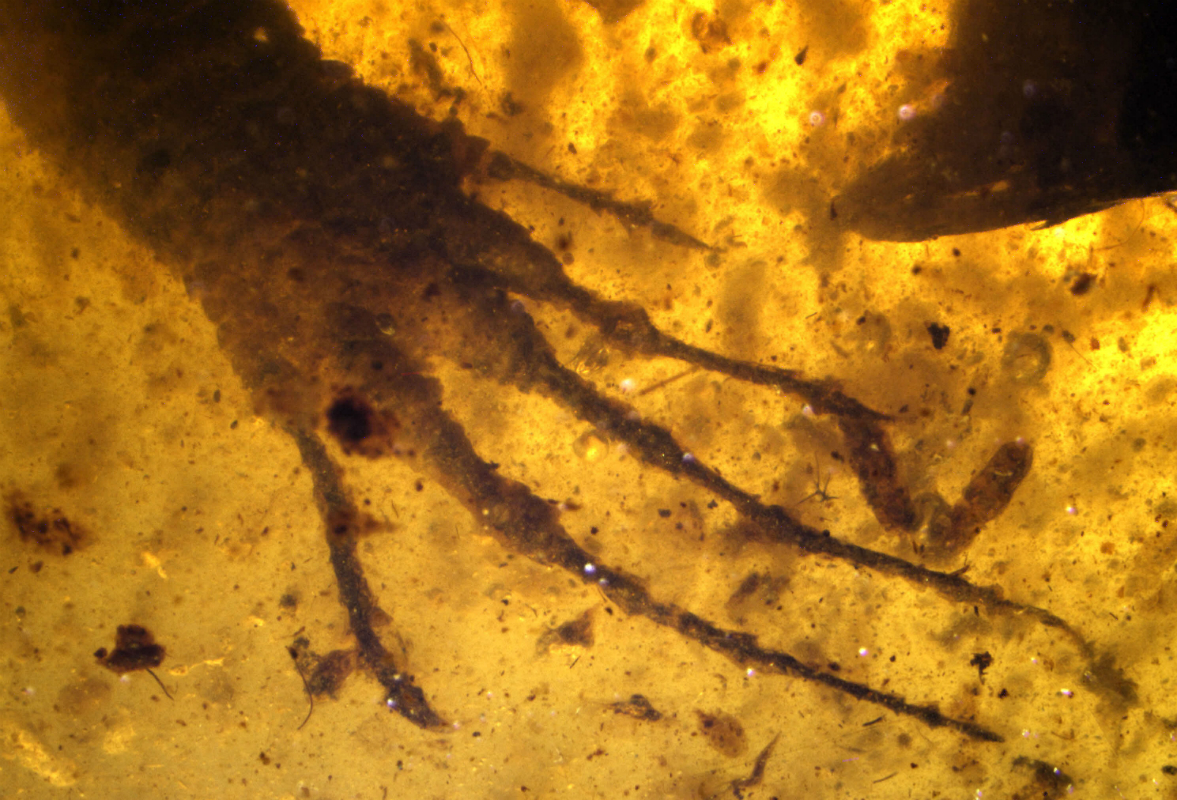

Toe the line

A toe on the isolated, preserved hind leg of a Cretaceous lizard, at 4X magnification. The amber also contained a layer of sand grains with slime mold clinging to them, indicating that the lizard had been active on sandy ground.

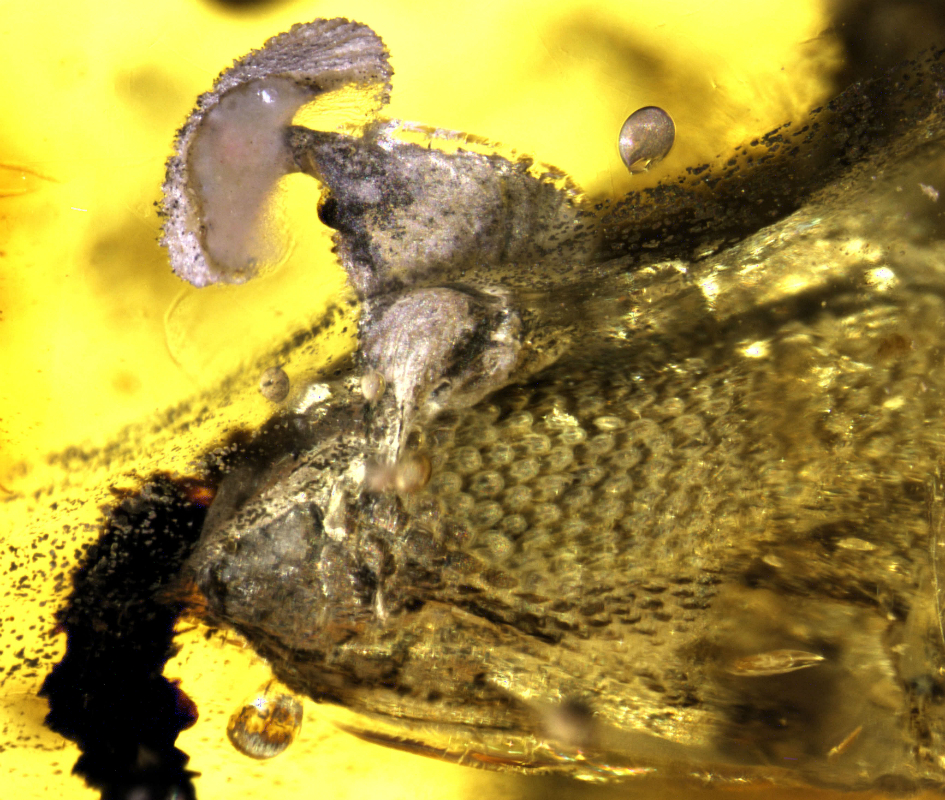

Say "aaaah"

Soft tissues rarely survive in fossils preserved in rock, but amber can protect delicate structures, keeping them intact for millions of years. This lizard's protruding tongue is visible as a grayish blob near the top of the frame, at 5X magnification.

Putting his best foot forward

The left forefoot of a lizard that was preserved as a hollow body cavity, surrounded by a clear, scaley epidermis.

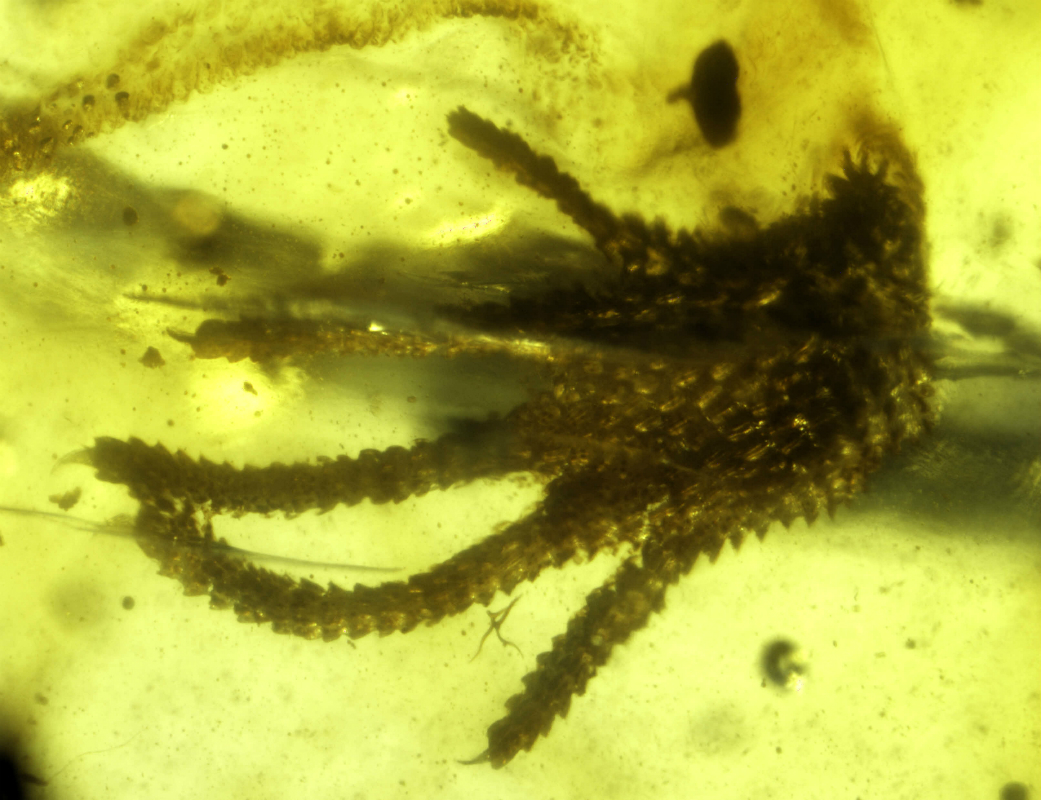

"There are things more horrible than death"

Long, spindly toes on the right foreleg of this specimen prompted the researchers to nickname it "Nosferatu," after the long-fingered vampire from the 1922 silent movie by F. W. Murnau.

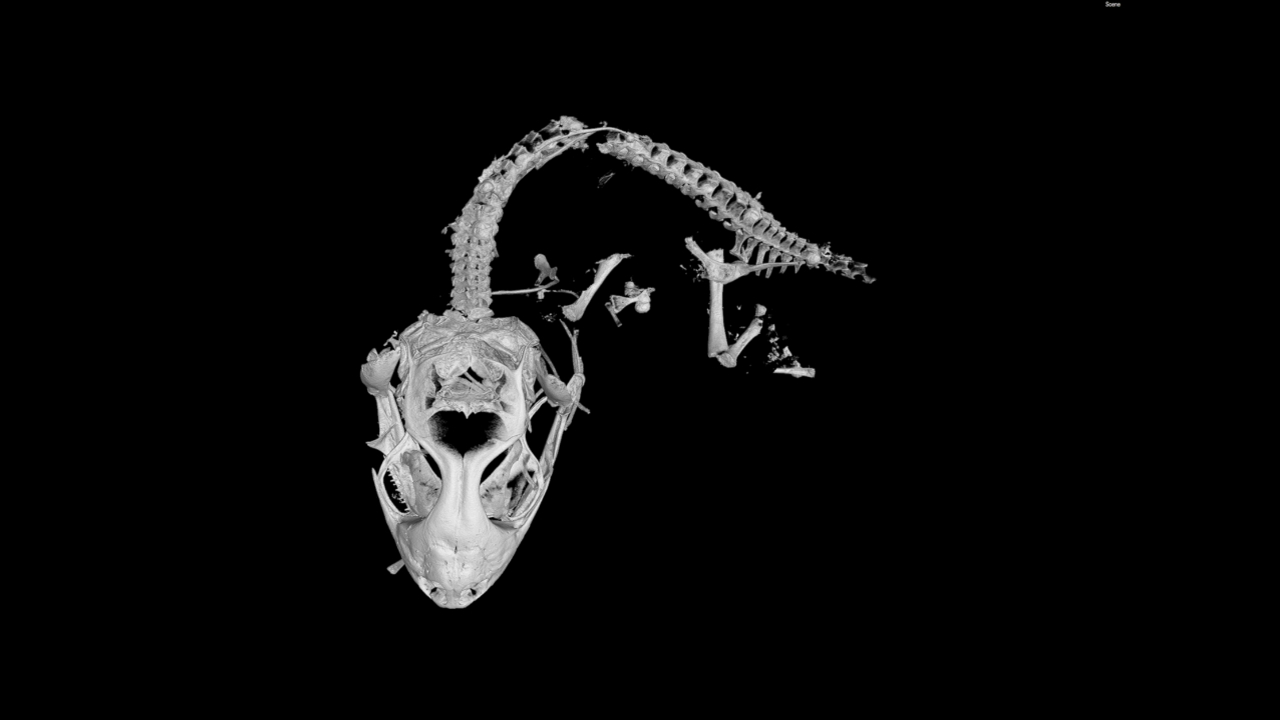

The lovely bones

Computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans allowed scientists to build 3D digital models of the trapped lizards. Amber preserved the skeleton of this gecko-like lizard, particularly its skull, mandibles, 26 vertebrae and pelvic bones. The soft tissues either decayed or were scavenged before resin completely covered the skeleton.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

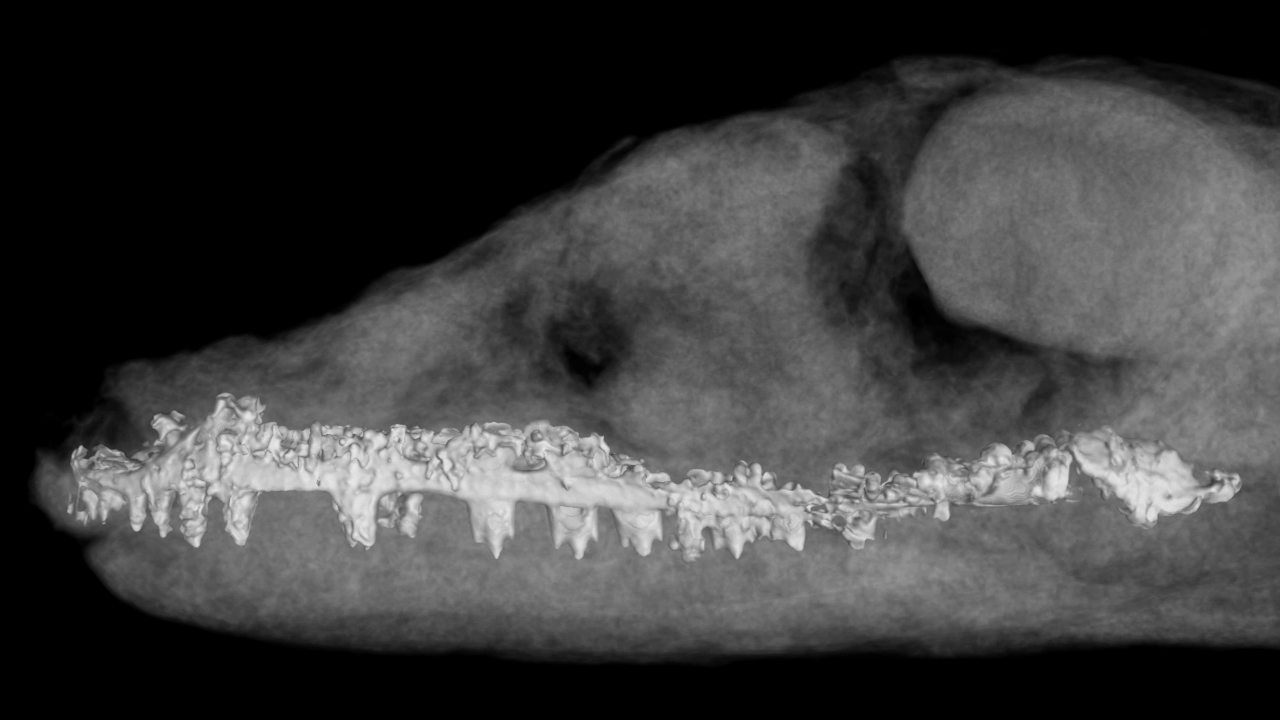

Imprints in amber's "memory"

Even if the lizards' bones weren't preserved, sometimes they left "air bubbles" behind in the amber that held their former shape. Scientists used these to cast models of internal structures, like this tooth row.

On the tip of his tongue

In this specimen, scientists observed epidermis with some coloration, the skeleton and some organs — the tongue, for example — that were mostly intact.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.