A Demon Ate the Sun: How Solar Eclipses Inspired Superstition

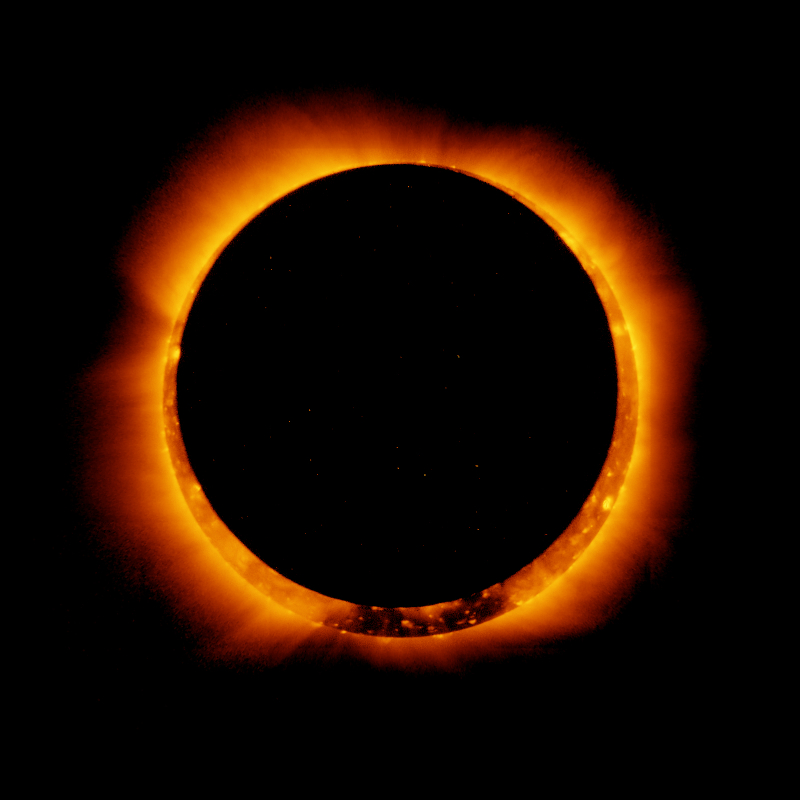

The first and only total solar eclipse of 2016 will roll across the sky this week. Total solar eclipses — when the moon's shadow blocks the sun entirely — are spectacular events, highly anticipated by astronomers, astrophotographers and casual spectators alike.

But it wasn't always that way.

The gradual darkening of the sun was once cause for alarm, linked to evil auguries or the activity of the gods. Throughout history, cultures around the world sought to provide context and explanation for eclipses, and like the eclipses themselves, the legends attached to the events were dramatic. [Sun Shots: Amazing Eclipse Images]

Left in the dark

This week's total solar eclipse will be visible from Indonesia and from the North Pacific Ocean early on Wednesday (March 9) local time, (late Tuesday, March 8, EST). During the celestial event, the sun is expected to be completely obscured for 4 minutes and 9.5 seconds.

Total solar eclipses occur when the moon's umbral shadow, the innermost and darkest part, is cast over the sun at a specific point during the moon's orbit: when it is close enough to Earth that the shadow completely obscures the sun's light. Witnessed firsthand, the effect is unsettling: The sky is gradually overcome by a creeping darkness that is jarringly out of sync with the familiar rhythms of day and night.

And for many ancient peoples, that meant one thing — trouble, said Edwin C. Krupp, astronomer and director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The word "eclipse" is derived from the Greek term "ekleipsis," meaning "an abandonment," Krupp wrote in his book, "Beyond the Blue Horizon: Myths and Legends of the Sun, Moon, Stars and Planets" (Oxford University Press, 1992). And during an eclipse, when the sun "abandoned" people to the darkness, many responded with terror and anticipation of disaster.

Krupp detailed a 16th-century account of Aztecs in central Mexico written by a Spanish missionary named Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, who described people reacting to an eclipse with "a tumult and disorder."

"There was shouting everywhere. People of light complexion were slain [as sacrifices]," de Sahagún wrote, according to Krupp, adding, "It was thus said: 'If the eclipse of the sun is complete, it will be dark forever! The demons of darkness will come down. They will eat men.'" [The Surprising Origins of 9 Common Superstitions]

Krupp also relayed an account from ancient Mesopotamia, in which it was said that an eclipse heralded that "an all-powerful king would die," and that "a flood will come and Ramman [the storm and weather god] will diminish the crops of the land."

And in Australia, eclipses were viewed negatively by many — but not all — Aboriginal groups, "frequently associating them with bad omens, evil magic, disease, blood and death," said a study published in July 2011 in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. Medicine men and community elders would try to counteract an eclipse's evil portents by chanting, singing, and throwing sacred or magical objects toward the sun, the authors explained.

Swallowing the sun

Many cultures attributed the sun's partial or total disappearance to hungry demons or gods with runaway appetites. Krupp detailed Mayan glyphs that hinted at a giant serpent swallowing the sun during an eclipse. Chinese and Armenian tales referred to dragons, while Hungarians claimed a giant bird was the culprit. The Buryats, an indigenous group in southern Siberia, blamed a giant bear, and the Shan people in what is now Vietnam described the sun-swallower as an evil spirit that took the form of a toad. [The 7 Most Famous Solar Eclipses in History]

For the Vikings, eclipses were caused by a sky wolf, whose name, Skoll, meant "repulsion." People would attempt to retrieve the temporarily stolen sun by making as much noise as possible, so as to scare the wolf into abandoning his meal, according to the 13th-century Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson, who wrote the book "Tales from Norse Mythology" (University of California Press, 2001).

And some of these sun-eaters took even more monstrous forms, Krupp recounted. Yugoslavians linked solar eclipses to a type of werewolf called the vukodlak, while western Siberia's Tatars told of a vampire that tried to swallow the sun and failed after burning his tongue. In Korea, the king of the "Land of Darkness" tasked his Fire Dogs with stealing the sun to brighten his gloomy domain.

In the ancient Indian poem "Mahabharata," the head of the demon Rahu — decapitated by the god Vishnu for drinking an immortality potion — pursued the sun that betrayed him, seeking to swallow it. But even when Rahu succeeded, it was only a matter of time before the sun re-appeared, passing through the demon's severed throat, Krupp explained.

Cosmic coupling

Other stories about eclipses assign a role to the moon in the sun's disappearance, according to Jarita Holbrook, a physics professor at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa and editor of the book "African Cultural Astronomy" (Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings, 2008).

"Mesoamerica and parts of Africa describe the sun and moon fighting during eclipses. Then there is the marriage of sun and moon among some of the North Americans. The marriage of sun and moon is often an act of creation in myths," Holbrook told Live Science in an email.

Holbrook explained that during the unfamiliar darkness of a solar eclipse, certain planets and stars could become visible, fueling myths that a cosmic coupling of sun and moon resulted in "births" of other objects in the sky.

"During the totality of a total solar eclipse, these bright points of light appear, only to disappear as totality ends," Holbrook said. "I can see how our ancient ancestors conceived of total solar eclipses as both a marriage and [a union] with the creation of stellar children."

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.