Weird Boneless Animal Rips Itself New Mouth at Every Meal

When it comes to genuinely cringe-inducing feeding adaptations, you'd be hard-pressed to find an example more hard-core than the hydra, which rips itself a new mouth at every feeding time.

Yes, a hydra literally "tears itself a new one," opening a gap in its own skin to make a feeding slit and sealing it back up afterward, when the meal is done.

And now, for the first time, researchers have examined exactly what happens on a cellular level during this unusual (and arguably horrifying) process. [Watch: Tiny Tentacled Creature Rips Itself Open to Eat Prey]

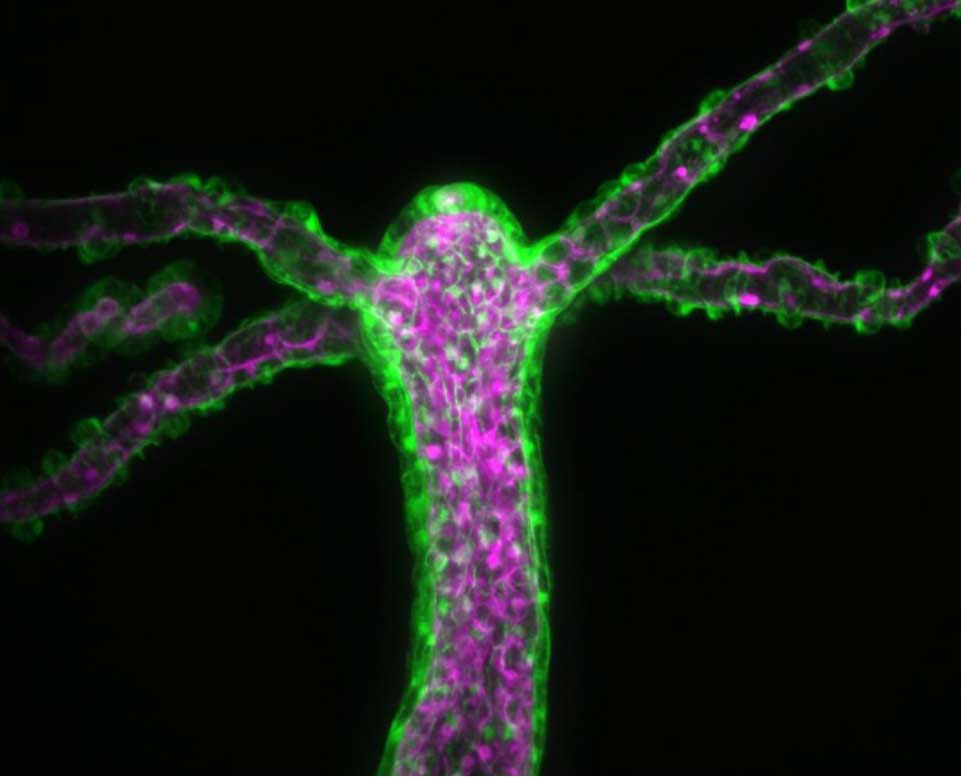

Hydra vulgaris is a tiny, tentacled freshwater invertebrate. It has a tubular body measuring less than 0.5 inches (1.3 centimeters) in length, with a grasping footlike appendage at one end and a ring of tentacles covered in sharp barbs at the other. If a small shrimp touches those tentacles, the hydra's barbs paralyze the prey. That's when the smooth expanse of skin at its head rips open to expose a mouth, which gulps down the prey and then reknits itself closed without a seam to show that there was ever a mouth at all.

"Because [the] mouth opening is so dramatic, it was suggested that cells need to rearrange to allow for the hydra mouth to open," study senior author Eva-Maria Collins, an assistant professor in physics and cell and developmental biology at the University of California, San Diego, told Live Science in an email.

Rip, heal, repeat

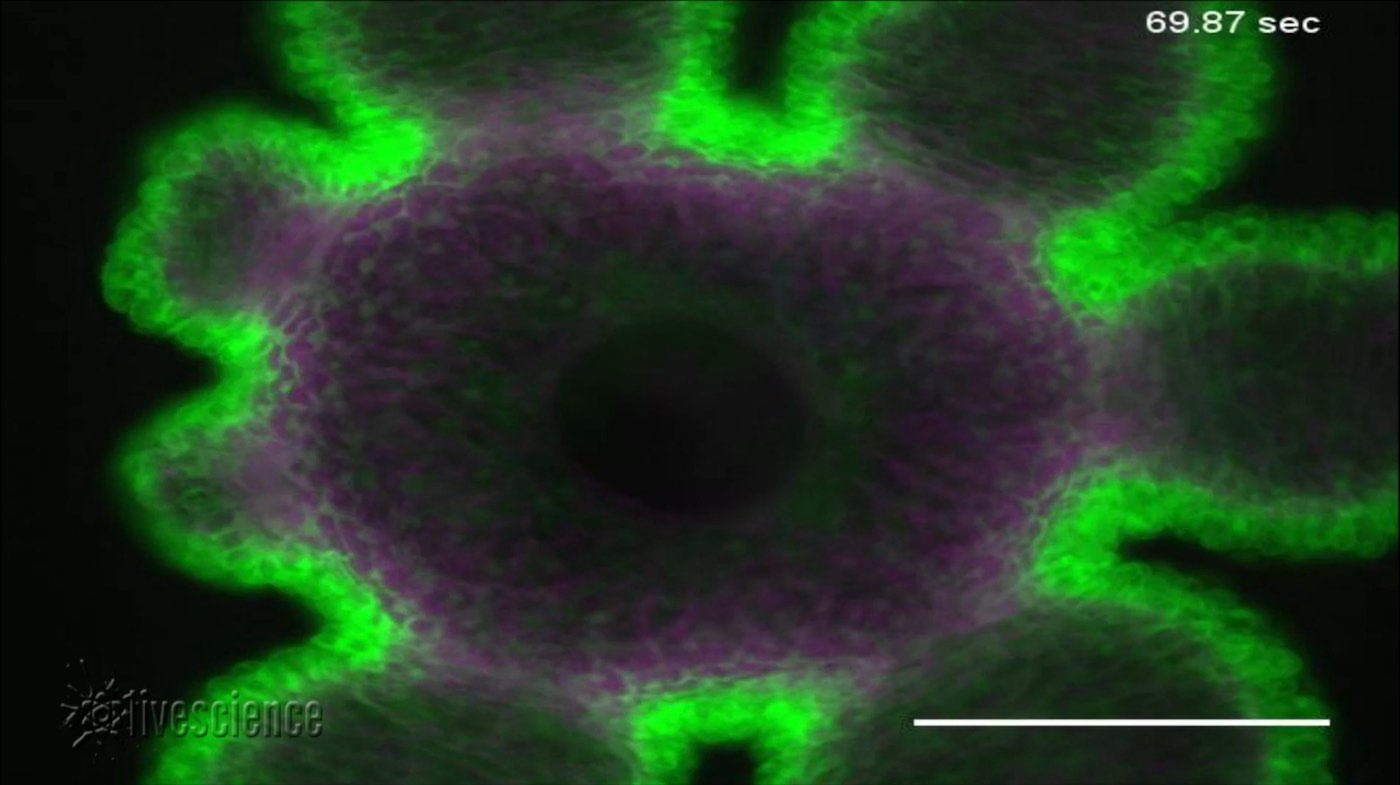

The researchers quickly discovered that the cells weren't rearranging — they were deforming.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When the mouth is closed, the cells have a roundish appearance," Collins said. "As [the mouth] opens, cells stretch dramatically, going from a roughly spherical to an ellipsoidlike shape."

And the transformation was dramatic — even the cell nuclei were warping, Collins said in a statement.

A hydra would trigger the stretching with electrical signals, which then cued muscular pulses that pulled its mouth open, Collins said. The muscle contraction was a key part of the mouth-opening process, the researchers found — if a hydra was given a muscle relaxant, its mouth wouldn't open.

While scientists may have revealed the cell-deforming process that opens and closes the hydra's peculiar temporary mouth, the benefits of this adaptation are yet to be discovered, Collins told Live Science.

"At this point in time, we do not have a good answer for this," she said. "It is an exciting question to study in the future."

The findings were published online today (March 8) in the Biophysical Journal.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.