Photos: Brainy, Horse-Size Tyrannosaur Discovered in Uzbekistan

T. Rex's Cousin Found

A horse-sized relative of the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex may not have been big, but it had a surprisingly advanced brain, a new study finds. The newfound dianosaur species, Timurlengia euotica, lived in what is now present-day Uzbekistan during the Cretaceous, about 90 million years ago. An analysis of its braincase showed that it had extraordinary low-frequency hearing, which likely helped it hunt prey. It may not have been the size of T. rex, but T. euotica provides evidence that tyrannosaurs' complex brains likely helped them become apex predators during the dinosaur age. [Read the Full Story on the Brainy Tyrannosaur]

Uzbek tyrannosaur

This illustration shows T. euotica prowling around Central Asia about 90 million years. Back then, the Central Asian climate was less like a desert, and more forested with rivers and lakes, said study lead researcher Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in the U.K.

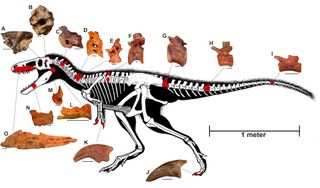

Dinosaur skeleton

T. euotica's skeleton, with the bones that paleontologists discovered highlighted in red. Until now, there were no known tyrannosaur fossils from the mid-Cretaceous. This newfound horse-size specimen shows that tyrannosaurs were still relatively small about 90 million years ago.

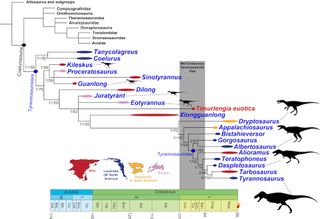

Family tree

T. rex has made the fierce dinosaurs known as tyrannosaurs immensely popular, but little is known about their family tree. Notice that T. euotica is the only known tyrannosaur rom the mid-Cretaceous. It was larger than the human- and dog-size tyrannosaurs from earlier time periods, but it was nowhere near the size of T. rex. This suggests that tyrannosaurs didn't get humongous until the last 20 million years of their evolution, Brusatte said.

In a recent study, Brusatte and Thomas Car, an associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin (who was not involved in the new study), created this family tree. Their findings suggest that T. rex, which lived from about 67 million years ago, was an invasive species from Asia.

Incredible brain

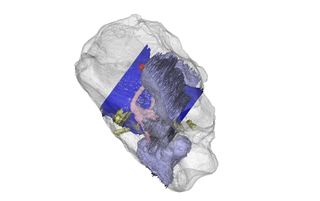

T. euotica's braincase — the part of the skull that holds the brain — was incredibly well- preserved, Brusatte said.

Skull scan

Study senior author Ian Butler, a research fellow in experimental geosciences at the University of Edinburgh, uses computer tomography (CT) to scan the skull of T. euotica.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

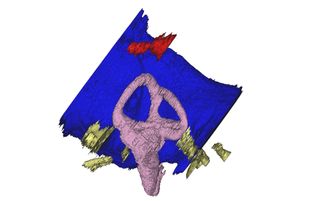

Digital analysis

A CT reconstruction shows what the inner part of the dinosaur's ear, nerves and vessels would have looked like.

Long cochlea

Another CT reconstruction of T. euotica's brain. Notice the long cochlea duct, shown in pink. A long cochlea duct suggests that the dinosaur could hear low frequencies, which likely helped it hunt prey.

Paleontologist party

Study co-authors and paleontologists Alexander Averianov (left) and Hans-Dieter Sues (right), who led the group that discovered the newfound tyrannosaur in Uzbekistan.

Dino duo

Paleontologists and study researchers Alexander Averianov (left) and Steve Brusatte (right). Averianov and Sues asked Brusatte to join the study because he had experience studying dinosaur braincases of tyrannosaurs and theropods (bipedal, mostly meat-eating dinosaurs).

T. euotica's stomping ground

The region in Uzbekistan where the researchers did the dinosaur fieldwork.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.