From Brains to Brawn: How T. Rex Became King of the Dinosaurs

The skull of a horse-size dinosaur, a distant relative of the colossal Tyrannosaurus rex, suggests that braininess was behind the beast's rise to dominance millions of years ago.

The dinosaur fossils, discovered in the desert of Uzbekistan, suggest that although early tyrannosaurs were small animals, they had advanced brains, said study lead researcher Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom. These keen brains likely helped tyrannosaurs become apex predators when they evolved into bigger beasts during the last 20 million years of the dinosaur age.

"Tyrannosaurs got smart before they got big, and they got big quickly right at the end of the time of the dinosaurs," Brusatte told Live Science. [See Images of the Fearsome Horse-Size Tyrannosaur]

T. rex may be famous, but little is known about its family tree. Tyrannosaurs originated about 170 million years ago in the mid-Jurassic, but they were mostly small, human- to horse-size dinosaurs at that time. Because of a 20-million-year gap in the fossil record, it's long been a mystery how these relatively small tyrannosaurs transitioned from marginal hunters to top predators, the researchers said in the study.

The new specimen fills that important gap. Paleontologists and study co-authors Alexander Averianov and Hans Sues discovered the tyrannosaur fossils in the Kyzylkum Desert of northern Uzbekistan. They dated the newfound species, named Timurlengia euotica, to the mid-Cretaceous, about 90 million years ago. During that time, Uzbekistan would have been hot and desertlike, but it also had forests, rivers and lakes, the researchers said.

"The middle Cretaceous is a mysterious time in evolution because fossils of land-living animals from this time are known from very few places," Averianov, of Saint Petersburg State University in Russia, said in a statement. "Uzbekistan is one of these places. The early evolution of many groups like tyrannosaurs took place in the coastal plains of central Asia in the mid-Cretaceous."

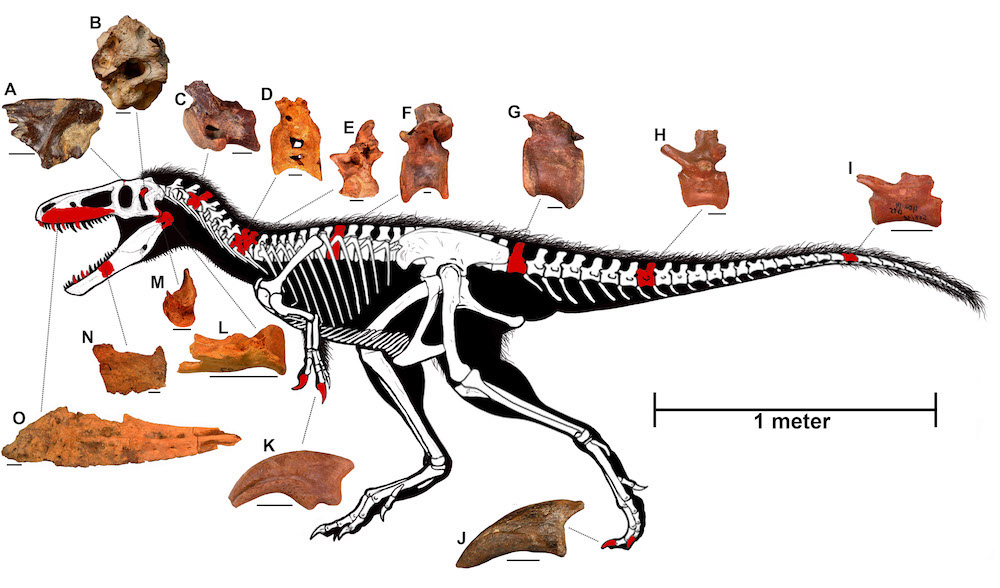

The paleontologists uncovered a number of fossils, including vertebrae, claws and teeth. But the tyrannosaur's braincase — the part of the skull that holds the brain — was, by far, the most significant finding, they said. In fact, the researchers teamed up with Brusatte because of his experience with studying the braincases of theropods (bipedal, mostly meat-eating dinosaurs).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using a computer tomography (CT) scan, the researchers found that T. euotica might have been only about the size of a horse and likely weighed up to 550 lbs. (about 250 kilograms) — a pip-squeak compared to the 9-ton (8 metric tons) T. rex — but its brain and senses were highly developed.

"It has a really advanced brain, really advanced senses," Brusatte said.

The CT scan revealed that T. euotica had a long cochlea in its inner ear, which would have enabled it to hear low-frequency sounds.

"Low-frequency sounds allow you to hear potential prey, maybe from a longer distance, but just better in general," Brusatte said. "Tyrannosaurs were better at hearing low-frequency sounds than almost any other type of dinosaur."

The scan also allowed the scientists to digitally reconstruct the dinosaur's sinuses, nerves and blood vessels within its skull. "It turns out that it basically has the same type of brain as T. rex, just smaller, Brusatte said. [Photos: 7-Year-Old Boy Discovers T. Rex Cousin]

The rest of the skeleton also provided clues about T. euotica.

"Timurlengia was a nimble pursuit hunter with slender, bladelike teeth suitable for slicing through meat," Sues, a curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., said in the statement. "It probably preyed on the various large plant eaters, especially early duck-billed dinosaurs, which shared its world."

The study was published online today (March 14) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.