Childbirth Painful for Neanderthal Women, Too

Neanderthal women had different birth canals than humans today. But childbirth was probably just as difficult, a new study finds.

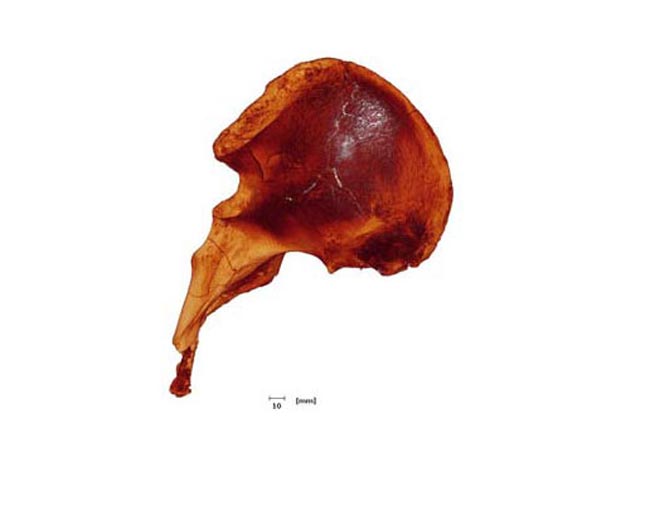

Scientists used fragments of a fossilized Neanderthal pelvis to reconstruct the birth canal. Though its shape is different from that of modern humans, the researchers concluded that it would have been similarly painful for the ancient hominids to give birth.

Neanderthals lived from about 130,000 to 30,000 years ago, and coexisted with our own ancestors. The fossils used for this study was discovered in Tabun, Israel, in the 1930s.

Paleoanthropologists Tim Weaver of the University of California, Davis, and Jean-Jacques Hublin of Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology used a medical CT (computed tomography) scanner to image the fossils. They digitally removed the filler material that had been connecting the fragments, and used a statistical model to estimate the size and shape of the remaining pieces.

The researchers found that where the birth canal in modern humans is widest from side to side at the top, and then alters to become widest from front to back at the bottom, the birth canal in Neanderthals is widest from side to side the whole way down. The difference means that modern human babies must rotate on their way out, but Neanderthal babies likely did not twist to exit the womb.

Despite the difference in shape among the two species, the birth canals are about the same size. Scientists also think baby Neanderthals' heads were roughly the same size as modern human babies'.

"We concluded that birth would have been about as difficult, but the mechanism would have been different," Weaver told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study, detailed in the April 21 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could help reveal why modern human babies twist during birth. Some experts think this process developed because modern humans' brains are bigger than our ancestors', but the new findings hint otherwise.

"This particular birth process is not a necessary consequence of expanding brain sizes, because Neanderthals also have large brains, but our study suggests they don’t have the same mechanism," Weaver said. "If we want to explain why we have this rotational birth, we have to come up with some other reason than saying that it's because we have larger brains."

- Top 10 Missing Links

- News and Information About Neanderthals

- The History and Future of Birth Control