My, what sharp teeth! 12 living and extinct saber-toothed animals

What sharp teeth!

The saber-toothed cat may be the most famous saber-toothed animal, but it's hardly the only one. More than a dozen kinds of animals — many of them now extinct — had saber teeth, including the saber-toothed salmon and the marsupial Thylacosmilus.

Today, saber-toothed animals include the walrus, musk deer and warthog, all of which grow incredibly long and sharp canines, the hallmark of a saber tooth. (Elephant tusks are long incisor teeth, and thus are not sabers.)

It's unclear how ancient animals used their saber teeth. Some experts think predators used these knifelike teeth to hunt and kill, slicing the neck vertebrae and spinal cords of prey, said Ross MacPhee, a curator of mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City.

Related: Big bites: Saber teeth compared (Infographic)

"[But] to me, this is totally improbable," MacPhee told Live Science. "The blades in Thylacosmilus are actually very thin, and neck vertebrae in ungulates are surrounded by tough muscles and ligaments. The teeth would have broken as the prey bucked around."

Instead, perhaps the sabers helped predators tear away at the prey's belly. "This is normal procedure for big placental cats," MacPhee said. "Cutting into the belly tends to bring the prey down on its knees so that it is easier to move in to crush their windpipes."

He added, "Sorry for the graphic details, but this is what happens, and it is supremely effective."

Here's a look at 12 living and extinct saber-toothed animals.

Musk deer

The musk deer (Moschus moschiferus) is one of the few saber-toothed animals living today. But it doesn't use its long canines for meaty prey — the ungulate is an herbivore, said Jack Tseng, a paleontologist at the AMNH.

"The males have these long sabers to fight each other during the mating season," Tseng told Live Science. "The reason you have such an over-the-top appearance is mating purposes, either to fight males or to impress females."

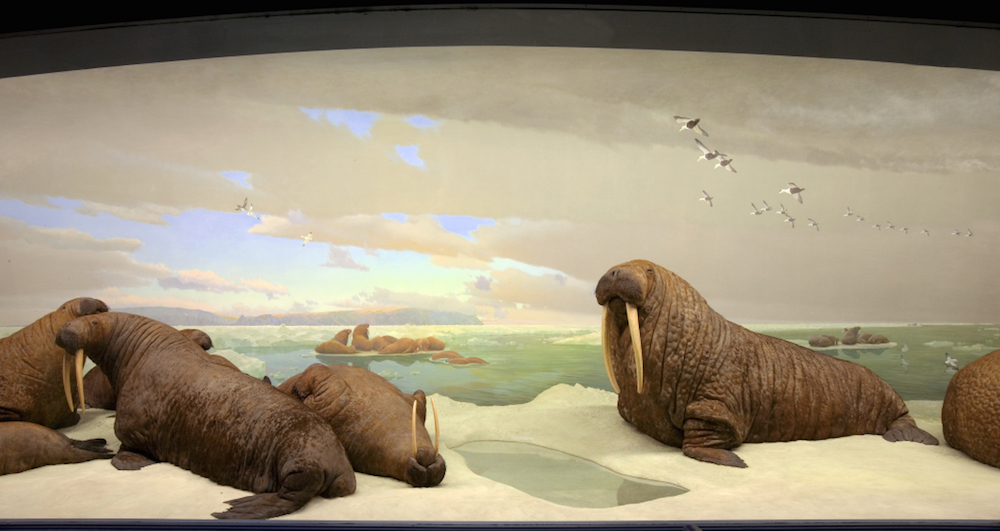

Walrus

The walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) has one of the longest sabers on record, with some males sporting canines extending more than a foot (0.3 meters) in length. Male walruses use their sabers both as a display and a weapon, Tseng said.

The sabers serve a variety of purposes. These long canines help them with "tooth-walking," or pulling their large bodies out of the water; breaking breathing holes in ice while swimming in the water below; and protecting their territory and harems, according to National Geographic.

Walruses may also use their sabers to help them stir up underwater sediment to search for mollusks, such as clams, Tseng said. But it's hard to say for sure — underwater photography is murky at best.

"As soon as the walrus hits the [sea] floor and starts to dig around, everything is just a blur," Tseng said.

Saber-toothed salmon

The saber-toothed salmon's teeth weren't oriented in a vertical saber-tooth fashion, but stuck out the sides of the fish's mouth like a scythe, said Edward Davis, the curator of fossil collections for the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, and an assistant professor of geology at the University of Oregon.

In fact, few experts call the fish (Oncorhynchus rastrosus) a saber-toothed animal anymore. Instead, researchers favor the names "spike tooth" and "giant salmon," because it was more than 6.5 feet (2 m) long and weighed about 660 lbs. (300 kilograms), he said.

O. rastrosus lived in the Pacific during the late Miocene and possibly the early Pliocene, from about 13 million to 4 million years ago. The filter feeder likely used its long teeth to fight for access to mates, slashing sideways at rival males, Davis said.

"[But] it is possible both sexes had these teeth, with females fighting for the best sites to make their nests, called redds," Davis said.

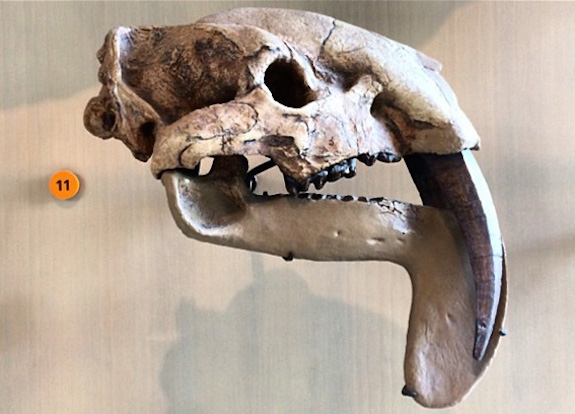

Extinct Walrus

Gomphotaria pugnax likely used its sabers to feast on shellfish when it was alive during the late Miocene, about 8.5 million to 5 million years ago. However, the species is only known by one skull, discovered in Southern California in 1980. The skull shows that the animal's upper and lower canines were large but worn down, possibly from prying shellfish off rocks and puncturing their hard shells, according to a 1991 study.

Saber-toothed cat

The most famous saber-toothed animal lived between about 2.5 million and 13,000 years ago, according to the San Diego Zoo. There are three known species of saber-toothed cat: Smilodon gracilis (the smallest one, with fossils found in eastern North America), S. populator (the largest one, whose fossils are found in South America) and S. fatalis (the intermediate-size one, with a range from North America to coastal South America).

Many specimens of S. fatalis are found in the La Brea Tar Pits of Los Angeles. Other Smilodon remains are found in forests or open plains, not in caves like the other saber-toothed cat, Homotherium, the zoo reported.

Smilodon's sabers were serrated like a steak knife. Its robust skeleton and powerful limbs suggest that it was an ambush predator, according to the San Diego Zoo.

Weird ungulate

Imagine a bizarre rhinoceros, and you might envision the Uintatheriidae group, whose species had hoofed feet, six horns on their head and saber teeth. Researchers have found Uintatheriidae fossils in Wyoming and Utah that date to about 40 million to 35 million years ago.

Perhaps Uintatheriidae used its sabers for display or fighting, Tseng said.

False saber-toothed cats

The nimravid family preceded the saber-toothed cat, but the two are completely unrelated. The saber teeth of the nimravid are an example of convergent evolution, when animals develop the same characteristics independently of each other because they occupy similar environments, Tseng said.

The nimravid lived during the late Eocene, and went extinct about 9 million years ago, according to Prehistoric Wildlife.

Catlike carnivore

Animals in the Barbourfelidae family certainly look catlike, but they aren't true cats. Researchers used to classify them in the nimravid family, a group known as "false saber-toothed cats." But subtle differences caused researchers to place Barbourofelids in their own family.

Barbourofelids appear in the fossil record from about 20 million to 10 million years ago, mostly in Eurasia and Africa, although at least one known genus lived in North America, Tseng said. Skeletal analyses suggest that they were likely better runners than true cats. Barbourofelids also had powerful neck muscles, which may have helped them drive their sabers into prey, Tseng added.

Interestingly, the North American genus, Barbourofelis, maintained their baby canines into adulthood, even after shedding the rest of their baby teeth.

"That's probably an adaptation," Tseng said. "It's not as damaging to break your baby sabers because you have an adult set waiting to grow out."

The marsupial

The leopard-size Thylacosmilus had sabers longer than Smilodon's, but they were probably more fragile. Their teeth were long and thin, which suggests they were prone to breakage if they got hit from the side. In addition, Thylacosmilus had wimpy bite and a weak jaw, according to a 2013 study published in the journal PLOS One.

However, they had strong neck muscles, and could probably drive their sabers into the windpipes of prey. These South American marsupial mammals lived about 5 million years ago, at the end of the Miocene.

Ancient sabers

The saber-toothed gorgonopsians lived before the dinosaur age. They're part of a group called the synapsids, four-legged animals that were the predecessors of all mammals.

Gorgonopsians were top predators during the late Permian in southern Africa, according to the University of California, Berkeley. Fossil evidence suggests that some gorgonopsians, including the genus Lycaenops (which measured about 3 feet, or 1 meter, long), hunted in packs, the university said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.