Hidden Text in England's Oldest Printed Bible Revealed

Long-hidden annotations in a Henry VIII-era Bible reveal the messy, gradual process of the Protestant Reformation.

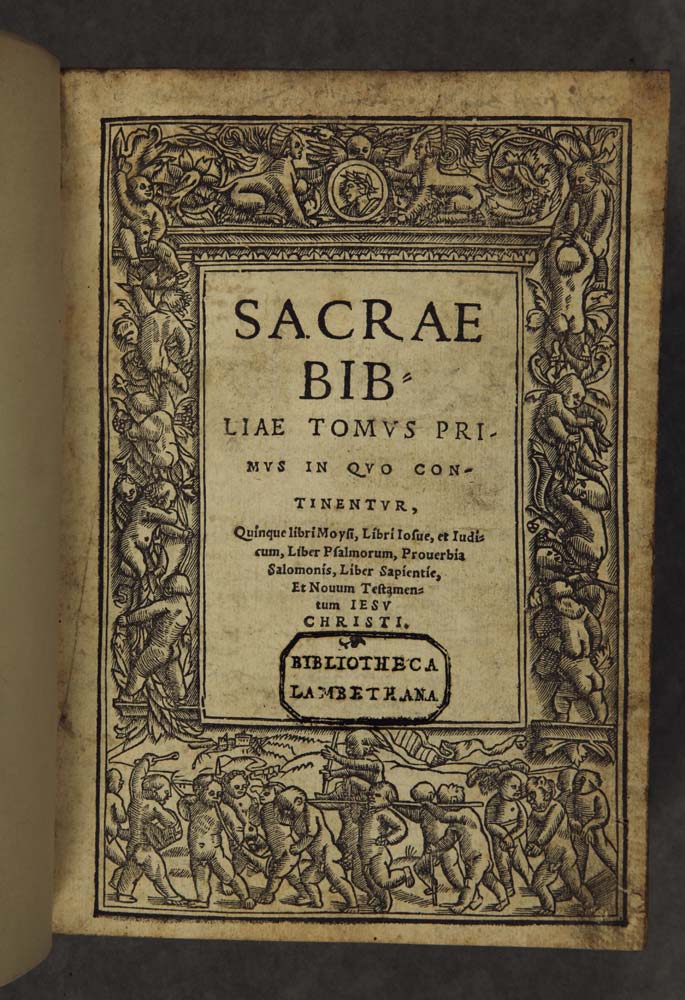

The handwritten notes were just discovered in a Latin Bible published in 1535 by Henry VIII's printer. There are only seven surviving copies of this edition, which features a preface by the king himself. The version with the annotations is in the Lambeth Palace Library in London.

"This Bible at first glance seems like a blank copy, so nothing interesting there, and very clean, which is the opposite of what we want it to be," said Queen Mary University of London historian Eyal Poleg, who is writing a book on the history of the Bible in England and who uses handwritten notes in Bibles to learn about how they were used.

But a closer look revealed that heavy paper had been glued over the margins of the Bible, hiding writing beneath. That writing would turn out to illustrate the Reformation in a nutshell. [See Images of the Annotated Bible Printed by Henry VIII]

Religious history

The 1535 Bible was published in a transitional time for religion in England. The Protestant Reformation was in full swing. Possessing an unlicensed translation of the Bible in English was a crime punishable by death. English scholar William Tyndale had nevertheless been working on a translation from Hebrew and Greek since the 1520s, a feat that earned him an execution by strangling in 1536. (Translating the Bible had long been dangerous work. John Wycliffe was the first person to attempt a full English translation, in the 1380s. At least one of his followers was burnt at the stake, the fire lit with manuscripts of the English pages. Wycliffe himself died of natural causes, but his bones were later removed from consecrated ground, burned and cast into the river by the order of the Roman Catholic Church's Council of Constance.)

Only a few years after publication of the 1535 Latin Bible, Henry VIII showed signs the Church of England was moving away from the authority of the Roman Catholic Church — called the English Reformation. He was already on the outs with the Roman Catholic Church after the dissolution of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, had declared himself the supreme head of the Church of England, and was well on his way toward dissolving England's monasteries, a process said to have funded Henry VIII's military campaigns. [Family Ties: 8 Truly Dysfunctional Royal Families]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Poleg's discovery of the annotations written during this period was mere happenstance. He was at the Lambeth Palace Library in order to examine one of the two 1535 printed Latin Bibles there. But he accidentally ordered the wrong one. While he was waiting for the librarian to retrieve the version he'd meant to order, he took a closer look at the volume in his hands. In the margins of one page, he noticed something odd.

"I saw there was a very small hole, and a few letters were peeking out," Poleg told Live Science. Someone had pasted heavy paper over the margins.

What lies beneath

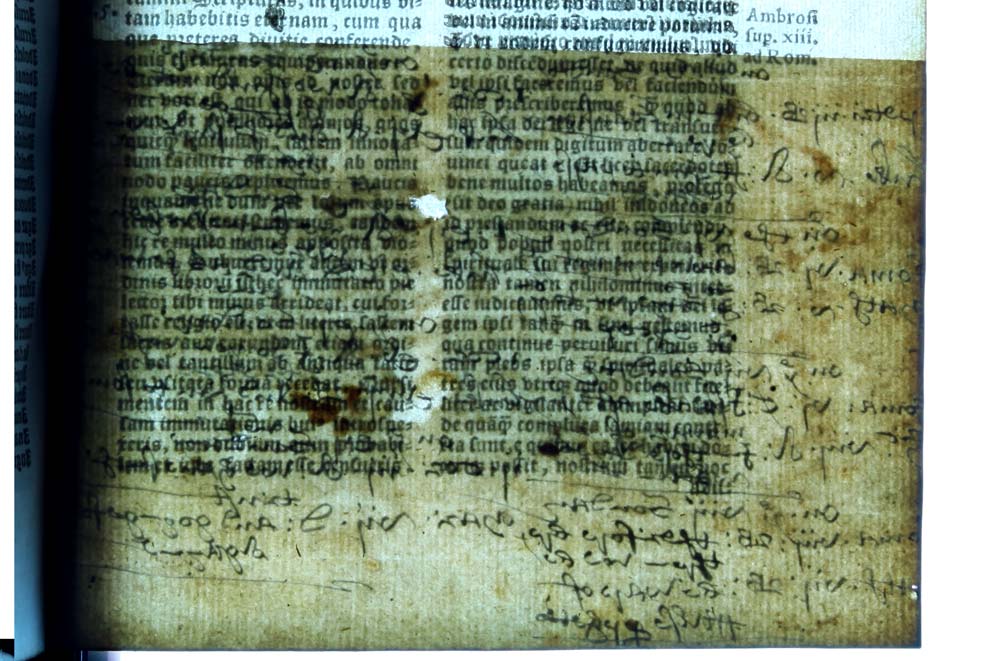

Poleg had to figure out how to see beneath the pasted-on paper — as removing the sheets would damage the original pages below. He used a light sheet, essentially a thin, paper-sized lamp that can slide under a page and illuminate any writing that might be hidden. The light sheet let him see that there was writing below the glued-on paper. It also let him see watermarks dating the paper to about 1600. But the printed text on the backside of the page showed through, too, making it impossible to read the handwritten notes.

"That's where I got stuck for about six months," Poleg said.

Finally, he turned to Graham Davis, an X-ray specialist at Queen Mary University of London's School of Dentistry. Davis took two long-exposure images of the pasted-over pages, one with a light sheet underneath the pages so that the annotations could be seen, and one without a light sheet. He then wrote a software program to virtually "subtract" the printed text, leaving the annotations behind. Suddenly, the hidden words were readable.

Transitional time

The annotations turned out to be tables of lessons, which are liturgical notes explaining which part of the text to read on particular days throughout the year (Advent, Easter and so on). The surprising discovery was that these tables of lessons were printed in English.

Further study revealed that the tables of lessons were copied from the "Great Bible," the first authorized English translation of the book, commissioned by the king's secretary Thomas Cromwell. The Great Bible was printed in 1539. The annotations were made at some point between then and 1549, Poleg said.

The presence of these English scribbles in a Latin book reveals how the Protestant Reformation happened on the ground, so to speak. By 1539, Henry VIII had issued legislation requiring all liturgy be given in English, not Latin. But "how people actually prayed, we don't know enough about that," Poleg said. "And this Bible tells us something."

"A lot of it is grayscale," he said. "It's not about going against Henry, or either Latin or English, but it's both Latin and English, both trying to do something they knew before, but not going head-to-head with legislation or the reigning monarch."

Other covered-up scribbles on the Lambeth copy of the Bible were less religious in tone. On the back page, Poleg found a handwritten promise by a Mr. James Elys Cutpurse of London to pay 20 shillings to a Mr. William Cheffyn of Calais. If Cutpurse (slang for "pickpocket") didn't pay, he'd be sent to the Southwark prison of Marshalsea.

Poleg tracked down Cutpurse's history and learned from a Londoner's diary that he had been hanged in July 1552. That means the handwritten promise had been made before then. Thus, the Bible tracks 17 years of tumultuous Reformation history in one document: It started as a royally decreed book, the first printed Latin copy of the Bible in England, then became a study guide on the shift from Roman Catholic Latin to Protestant English, and finally moved into secular hands, its use becoming more like a religious "talisman" than a liturgical text, Poleg said.

"Henry's breaking the religious establishment and their books are moving out of the church to all sorts of places," he said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.