With the Right 'Words,' Science Can Pull Anyone In (Op-Ed)

Paul Sutter is an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University and the chief scientist at COSI Science Center. Sutter is also host of the podcasts Ask a Spaceman and RealSpace, and the YouTube series Space In Your Face. Sutter contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

To paraphrase Galileo, "The book of nature is written in mathematical characters."

The language that physicists and astronomers use to describe the natural world around us and the vast cosmos above us is just that — mathematics. It's through theoretical equations, data analysis number-crunching, and hardcore computer simulations that scientists pry open nature's secrets from her jealous hands. [Images: The World's Most Beautiful Equations]

Mathematics is a fantastic tool, revealing more about the universe than we could've ever dreamt when the first scientists started applying rigorous methods to their natural philosophy. But that blessing is also a curse. Mathematics, the language that proves so adept at describing nature, is not the easiest language to translate into, say, plain English. That difficulty — the same difficulty in translating from any language into another — is at the root of much of the distrust some people have of astronomers and scientific findings. It's nothing new, unfortunately — just ask Galileo how much trouble he had.

Do you speak science?

Scientists have an undeserved reputation for being poor communicators, but this couldn't be further from the truth. A healthy fraction of a scientist's day is filled with communication: coordinating work with colleagues and students, writing papers and grant proposals, preparing and giving talks at conferences and workshops, and teaching. How else is a scientist supposed to convince their fellows that they've hit upon the Next Great Idea if those results aren't communicated clearly? [Scientists Should Learn to Talk to Kids]

Scientists are some of the strongest and most eloquent communicators you'll ever meet — when they're speaking their "native" language of mathematics and jargon. Jargon words are just shorthand expressions for complex topics, and any profession, from physicists to bakers, use it. It's just that bakers aren't usually called upon to report their findings to the public. And many scientists are up to the challenge of translating their findings into non-jargon English, but there's a problem: there's no good reason for them to do it.

The priorities for a scientist in our current academic system are, in order: 1) get grants, 2) write papers, and 3) anything else.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That "anything else" includes teaching, serving on committees, refereeing papers, and — in the tiny fraction of time leftover — engage with the broader community. Oh, and maybe spend some time with their families.

If you've ever wondered why most scientists don't go to the trouble of communicating their work with the public, there's your reason: there's no incentive for them to do it. There aren't any rewards, and there certainly isn't any money. When a scientist does engage with the public, say, by giving a public lecture or visiting a classroom, by and large they are doing it in their spare-spare-spare time, and doing it because they enjoy it.

So we (and "we" here means both scientists and the public) have a problem: the knowledge that scientists gain about the natural world stays relatively locked up within the scientific community, the scientists have no incentive to share it more broadly, and the public grows ever more distrustful of scientists. That reduces science funding opportunities, which means researchers have to work even harder to get grants, which means they have even less time for outreach ….

We need to break this cycle. Society needs to be scientifically literate to function, and scientists need public support to continue being scientists.

This is where storytelling comes in. Stories are powerful. They resonate with us on a human level in a way that bare numbers can't. And there are many creative ways to tell stories. Usually scientists are nervous to tell stories based on science — they are, after all, trained to be as precise and exacting as possible. Fortunately, there are many talented people around the world who are experts at telling stories — artists.

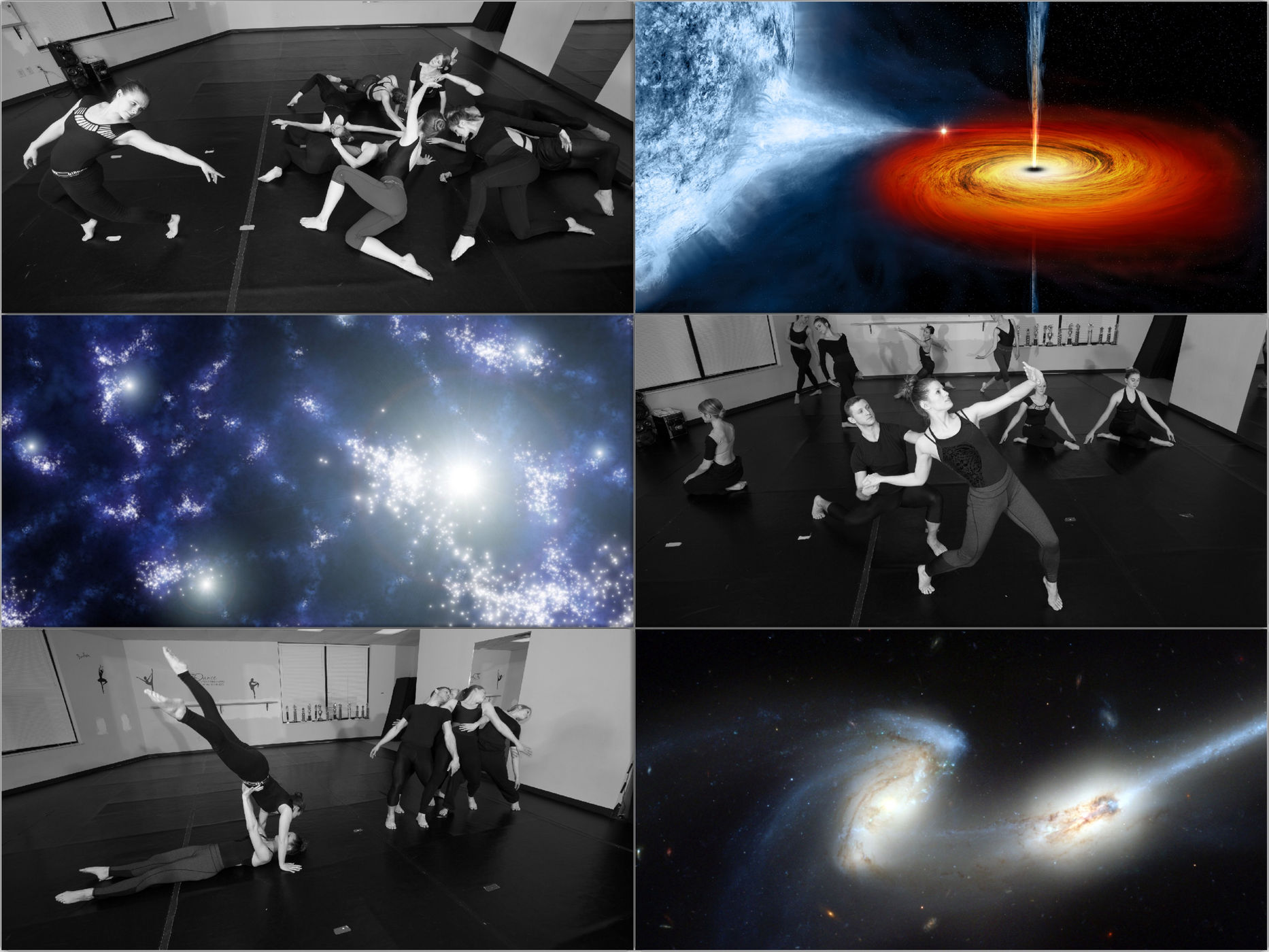

Such as dancers. Yes, dance. People moving their bodies to music. Dance is a natural "language" for interpreting and representing physical concepts: the way a dancer thinks about the world, in terms of transfers of momentum and flows of energy, isn't much different from a physicist. Endeavors like the popular "Dance Your Ph.D." program or a project I'm involved with, "Song of the Stars," take advantage of that natural connection.

Science as art and movement

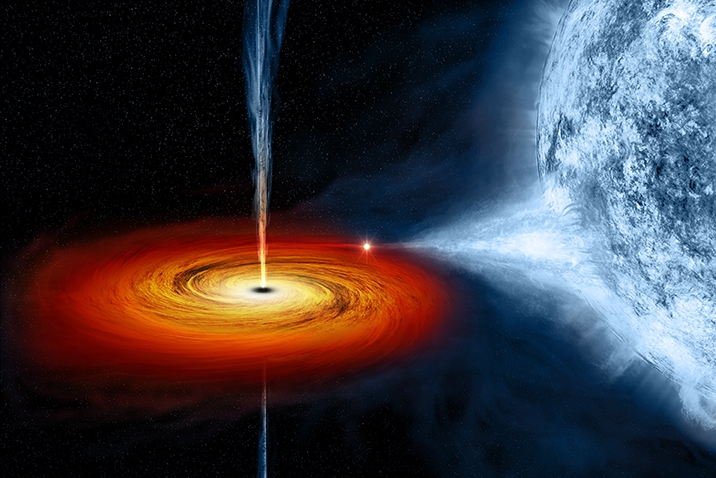

In "Song of the Stars," the dances reflect themes from astrophysical phenomena. We've all been wowed by Hubble images, but it's something completely different to be immersed in the formation of the first stars or to witness a companion being pulled into a black hole, as only dance can express. To have astronomy brought down to Earth and be brought to life. To explore and share astrophysical phenomena in new and creative ways. To interpret the motions of gas and the play of complex forces using only the movement of the human body. To be told a story in a way that emotionally connects with us. And there are so many wonderful stories to tell about the universe, stories revealed by the scientific process but not usually exposed to the public in a way that they can appreciate and enjoy. [Do Science and Art Share a Source? - Café Panel Chat]

"Song of the Stars" is a blending of astronomy and dance to tell the life stories of the stars above. From the first revolution of light more than 13 billion years ago in a dark universe, to a galactic collision that sparks a new generation, to the loss of a companion into a black hole, to a spectacular supernova that sends one last message across the universe. Dance pieces depicting these scenarios are interwoven with narration that conveys the science and gives the audience enough information to fully appreciate the creative work of the artists.

I'm continually fascinated by the ever-unfolding mysteries that the universe presents to us, and I want to share those mysteries with anyone I can. This is why I started working with Seven Dance Company to create "Song of the Stars." By sharing what I know with dancers and choreographers, we're working together to translate mathematics and jargon into new languages and use those new languages to tell stories that connect with us in different, emotional ways. This process sacrifices technical details, which is fine. I'm trying to communicate intuition, notinformation. If an audience wants reams of complex text and mathematics, they're already well-served.

Speaking from a common voice

Most people may not realize the beauty and drama that plays out in the heavens above, because it's never been shared with them in a way that makes them care. Many people are immediately "turned off" by science or space concepts. But maybe dance can reach them. Maybe other artistic expressions can communicate to them. Maybe if science is shared with them in a way that they can appreciate and enjoy, we can break the cycle of distrust. Maybe if science knowledge is presented in new ways — away from meaningless soundbites or contextless data points — audiences can gain an understanding of, and an appreciation for, what scientists do.

And maybe those audiences can gain an appetite for more. We're all curious; it is part of what makes us human. If that curiosity can be awakened — or reawakened — maybe the next time scientists beg the public for money they won't be immediately dismissed. Maybe the next time a research group publishes a new result, it's met with joy and fascination from all corners of society. Maybe a kid who never realized he or she could be a scientist pushes toward a new career.

The point of combining science with the arts isn't to necessarily dictate what the artist creates, but rather to explore a shared experience and find the common ground between the disciplines. The point is to inspire artists and to bring science to new audiences who wouldn't normally be interested in the topics.

To reveal and revel in what science truly is: an expression of our shared human curiosity, expressed in the language of mathematics, but translated to make it enjoyable by everyone.

"Song of the Stars" is supported by a Kickstarter campaign. Learn more by listening to the episode "What's the point in talking about science?" on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.