Aloha, You Old Bat: Extinct Critter Doubles Hawaii's Land Mammal Species

Hawaii just doubled the number of known land mammal species that are native to the islands, thanks to the discovery of a number of fossils representing a tiny bat named Synemporion keana.

Found in 13 cave sites over five islands — Kauai, Oahu, Molokai, Maui and Hawaii —the fossils described in a new study represent at least 110 individuals and reveal a bat that was notably different from the only other land mammal species that is endemic to Hawaii — the Hawaiian hoary bat.

In fact, combinations of the new bat's physical features were so unique that the scientists determined it was a new genus in the bat family tree, as well as a new species. [Photos: The Creatures That Call Lava-Tube Caves Home]

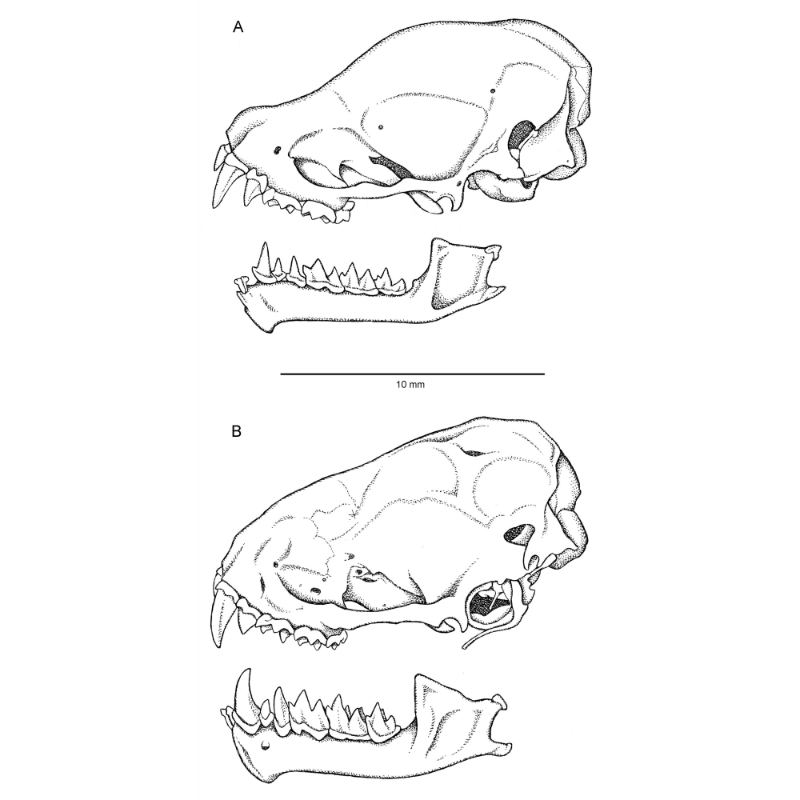

S. keana probably measured about 2 inches (5 centimeters) long, with a skull length of about 0.4 inches (1 cm), the scientists reported.

Many of S. keana's bones were found in the same locations as hoary bat fossils, suggesting to scientists that the bats shared habitats. But the new bat came to the islands much earlier than the hoary bat, arriving about 320,000 years ago, the researchers found, while the hoary bat's arrival dates back no more than 10,000 years.

The bats coexisted for thousands of years until S. keana went extinct about 1,100 years ago, likely because of human colonization and the introduction of invasive species, the study authors suggested.

Encrusted in crystals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

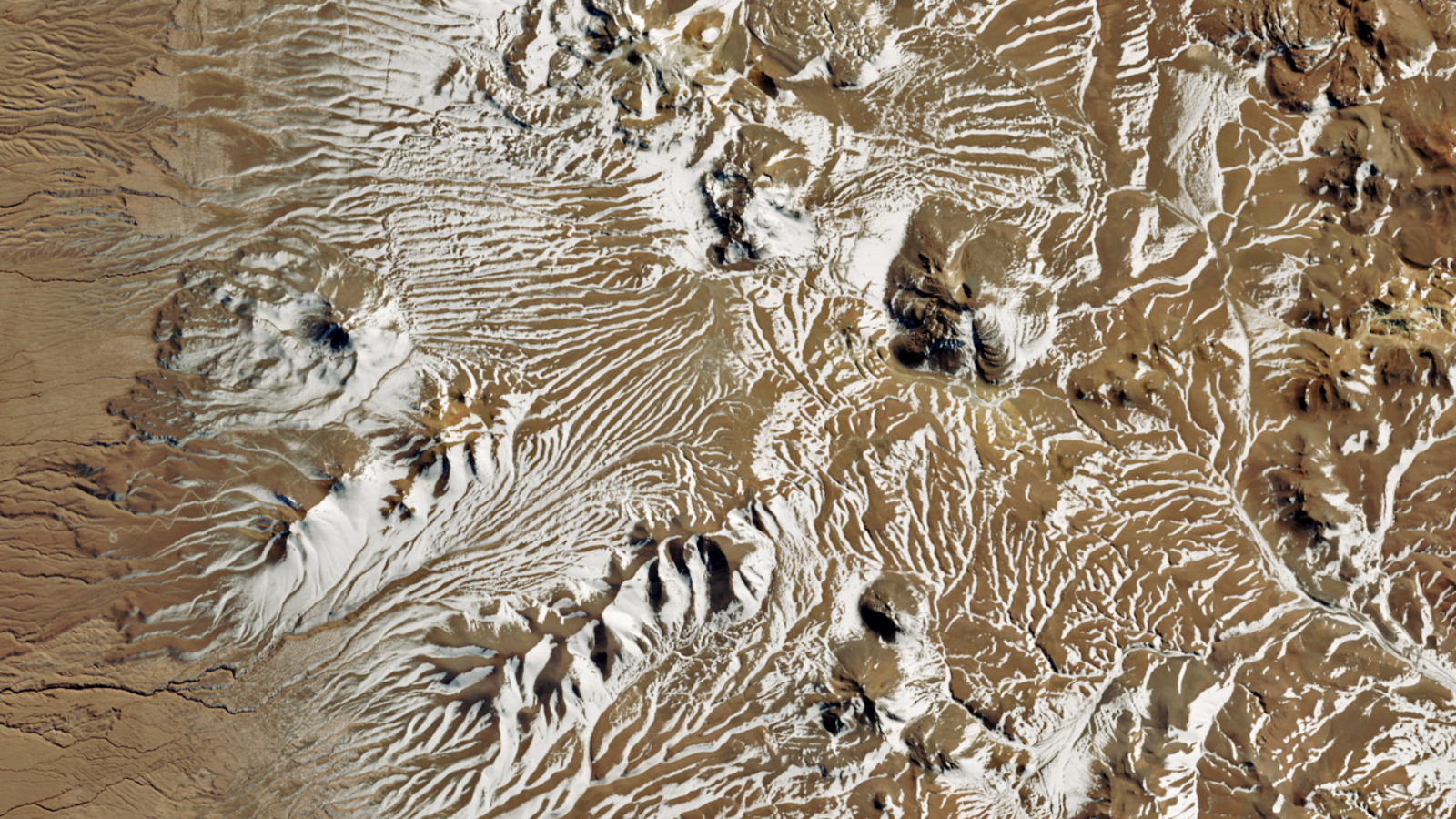

It was 1981 when entomologist Francis Howarth, one of the study's co-authors, discovered near-complete skeletons of the bat on Maui. A distinguished research associate in natural sciences at Hawaii's Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Howarth told Live Science that he was investigating the fauna, evolution and ecology of Hawaiian lava tubes — expansive, cavelike channels formed by flowing lava beneath hardened lava crusts. [Photos of a Rising Lava Lake in Hawaii]

In one cave, he noticed something unusual — a small skeleton embedded in the wall. The tiny bones were overgrown with mineral crystals, "So I knew it was very, very old," Howarth said. He gathered several more accessible specimens from the cave floor, including a near-complete skeleton, and brought them to the late Alan Ziegler, a mammalogist colleague at the Bishop Museum and co-author of the new study.

Howarth recalled that Ziegler already suspected the existence of a "mystery species" that had once lived on the islands, based on assorted individual bones that were discovered over time. Scientists were able to tell that — whatever this animal was — it was smaller than the hoary bat. But no skulls had been found, and there weren't enough of any other bones for scientists to identify the animal they belonged to.

All of that changed with Howarth's discovery. Now that Ziegler had a near-complete skeleton as a frame of reference, individual bones found in other locations began to fall into place.

A mosaic of features

Ziegler's death in 2003 temporarily suspended work on the project, which resumed with the participation of Nancy Simmons, curator-in-charge in the mammalogy department at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, who joined the investigation in 2006.

Simmons, who studies living and fossil bats, told Live Science that S. keana's skull shape — with "a distinct forehead" — told them right away that they were looking at a different species from the hoary bat, which doesn't have a well-defined forehead.

But no single feature placed S. keana in a new genus. Rather, it was a mosaic of features that don't appear together in any other known bat species: a particular number of teeth, a certain shape in the molars and skull, and specific proportions of bones in their wings.

"Compared across all other genera of known bats, this particular combination doesn't appear in any of them," Simmons said.

While the isolated Hawaiian Islands are known to host a diverse array of birds and invertebrates, until now, the number of its native mammalian land fauna could be counted not just with one hand, but on one finger. The discovery of S. keana, which doubles the number of endemic Hawaiian land animals, is a surprise that carries an important lesson about diversity, Simmons said.

"It just goes to show that you may think that you know what the diversity of something like an island fauna was like," she said. "Fossils can provide new information, which can be really interesting. And the fossil record of all mammals is always full of surprises."

The findings were published online March 21 in the journal American Museum Novitates.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.